‘Sully Island’: Where the waters part for you

Simon Calder spends a week visiting islands around the UK. Part 5: Sully Island, Glamorgan

All too often in travel, your instincts, the internet and local opinion conflict. When that happens, always go with what the locals say. But during the Welsh adventure in my insular tour of the great outdoors, I didn’t.

“Dead end,” read the sign planted on the cliff top about halfway along the Wales Coast Path from Cardiff to Barry.

I ignored it, but as I plodded on across the muddy headland my spirits sank at about the same rate as my boots disappeared into the Glamorgan gloop. Eventually I reached the mudslide to which the sign had referred, and retraced my soggy steps.

The creator of the sign had the last laugh. Inscribed on the back of the dead-end sign was: “Told you.”

A superstitious island-hopper could begin to feel that the gods were against him. But a local with a key to the caravan park unlocked the gate and let me through, urging me to hurry to the road before the incursion was spotted.

Over the hill and not too far away was the main attraction of my hike: Sully Island.

Third isle lucky.

“Caldey Island is home to grey seals,, seabirds and a red-topped, whitewashed monastery,” the Lonely Planet guide to Wales explains. But my friend Lawrence, who can gaze upon the Cistercian community from his home in Tenby, warned it was closed because of coronavirus.

“Flat Holm has a unique island character,” the Cardiff Harbour Authority website relates, “with a sense of wilderness, remoteness and isolation”. Not to mention “extensive views from and across the island to the coast of England and Wales”. Except this summer: “Unauthorised visits are not permitted and anyone found accessing the island will be asked to leave.”

Even my target, Sully Island – just off the coast as it curls around from east- to south-facing – comes with complications. Lawrence warned: “The locals get a bit angry if you get stuck on the island and they have to come and rescue you.” But getting there, and beyond, comprises a large part of the fun.

The Cardiff sky and Cardiff Bay had adopted the same hue, on the gloomy side of grey. The rain was a grade of heavy drizzle that is disheartening rather than depressing. But the joys of the corrugated coastline unwinding westwards from the Welsh capital prevailed.

First, you walk (or cycle) across the barrage that has tamed the tide and gives a grand perspective on Cardiff’s reborn waterfront.

Pier pressure: Penarth has one of the finest from the Victoria era (Simon Calder)

Next, clamber to the heights of Penarth and down to the Esplanade, where Victorian resort has kept the best of the 19th century – notably the pier – and embellished it with absurdly appetising restaurants.

An hour spent on a stirring cliff-top path takes you closer to Weston-super-Mare, just 10 miles away through the haze (or about half a day’s drive over a bank-holiday weekend) – and deep into radio history.

High on a cliff in May 1897, Guglielmo Marconi transmitted the first radio message across from here at Lavernock Point across open sea. The pioneer did not aim as far as the Somerset coast, but his signals reached Flat Holm island (which was open that summer).

“Are you ready?,” stuttered the first Morse message to cross the water. The rest was communication history.

“Are you ready?,” I wondered as I wandered west to Sully Island. Despite the dead-end detour, I reached Swanbridge – the village to which Sully is intermittently tethered – earlier than anticipated.

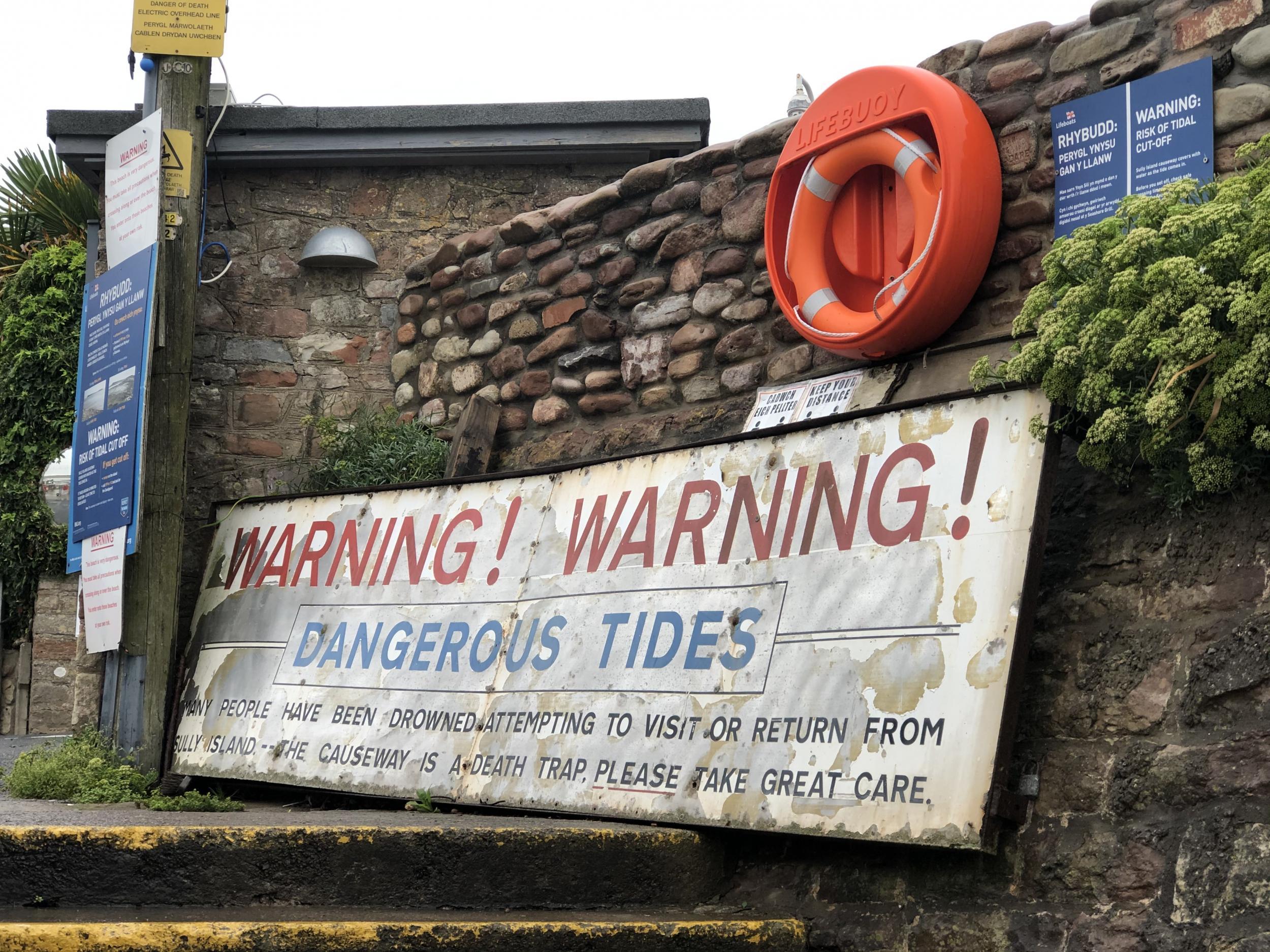

Sully is connected to Swanbridge by a natural causeway. For much of the moon’s cycle, the hyper-tidal Bristol Channel rushes over it, one way or other. For a few hours around low tide, you can walk across.

A digital clock counts down with the outgoing water: “8:31,” it blinked. But I slithered across the exposed rocks to the water. Which, at quarter-past the hour exactly, parted to let me walk across.

After an unexpectedly Biblical experience, Sully was an uninhabited joy. The slabs of rock that lead you on to dry-is land look intricately carved by Inca masons. The dome of greenery comprises dense bracken and sparse grass, and it made for an exuberant hour of what could loosely be called fieldwork – exploring the crannies, noting the nooks, scampering to a summit of a good 60 feet or so.

“On a good day you can get a fantastic view of the Quantocks,” I had been told. But close up can be more than enough.

Sully, as far as I can tell, is not twinned with another island. Perhaps Barry Island should sign it up. Just along the coast, at the end of the hike, is this cheerful resort.

Anyone hoping to find a location encircled with water will be disappointed with Barry Island, but the rest of us can enjoy the promenade, seek enrichment in the Treasure Island amusement arcade – or get cheap thrills at the Island Pleasure Park, where a mural invites you to travel: “Here. There. Everywhere.”

One day. But for now, island life in South Wales will suffice.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks