Ski in the Dolomites: War and piste

Ski through history amid one of the Great War's most dramatic theatres – the high-mountain splendour of the Dolomites. Leslie Woit reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.'And for us," declares Marcello, "the war begins." I'm on a multi-day guided Great War Ski Tour, where trivial laments of the modern-day skier – lift queues, runny noses, sore legs – take a back seat. One hundred years ago a very real war was waged here after Italy joined the Allies in April 1915 and declared war on Austria-Hungary a month later. Austro-Hungarian and Italian troops battled in places now famous for fur shops and cappuccino stops – Cortina, Val Gardena, Alta Badia, Marmolada, Sella, Lagazuoi, Tofane, Cinque Torri. From 1915 to 1917, the ski slopes of the Dolomites were on the war's frontline.

Mountain guide Marcello Cominetti and I slide towards the gondola entrance. Equipped with skins on our skis for climbing, as well as beacons, probes and shovels, we're skiing through the First World War – tunnels, battlefields, bridges and mountain tops. In comfortable juxtaposition, we will stop at different mountain rifugios and hotels each night – soaking up the blowout scenery, remarkable cuisine and fabulous skiing that South Tyrol now shares with the world.

Our bubble rises upwards from the village of Corvara, jagged peaks filling the window frame. At the summit, Marcello aims his ski pole across the valley, directing my gaze towards a formless white nob – Col di Lana, the epicentre of battles between Austrian and Italian troops. About 10,000 soldiers were killed protecting that innocuous-looking knoll, a vital link in the supply route for munitions and food from Venice to the mountains. Next to the treeline we make out Marcello's house; nearby, bunkers and holes from explosive charges are still discernible in summer.

It's a glorious morning-long ski on sunny pistes en route to Marmolada, the Dolomite's highest glacier and premier powder stash. Impressive as the boot-top powder promises to be from the top, it's far less miraculous than what we see next.

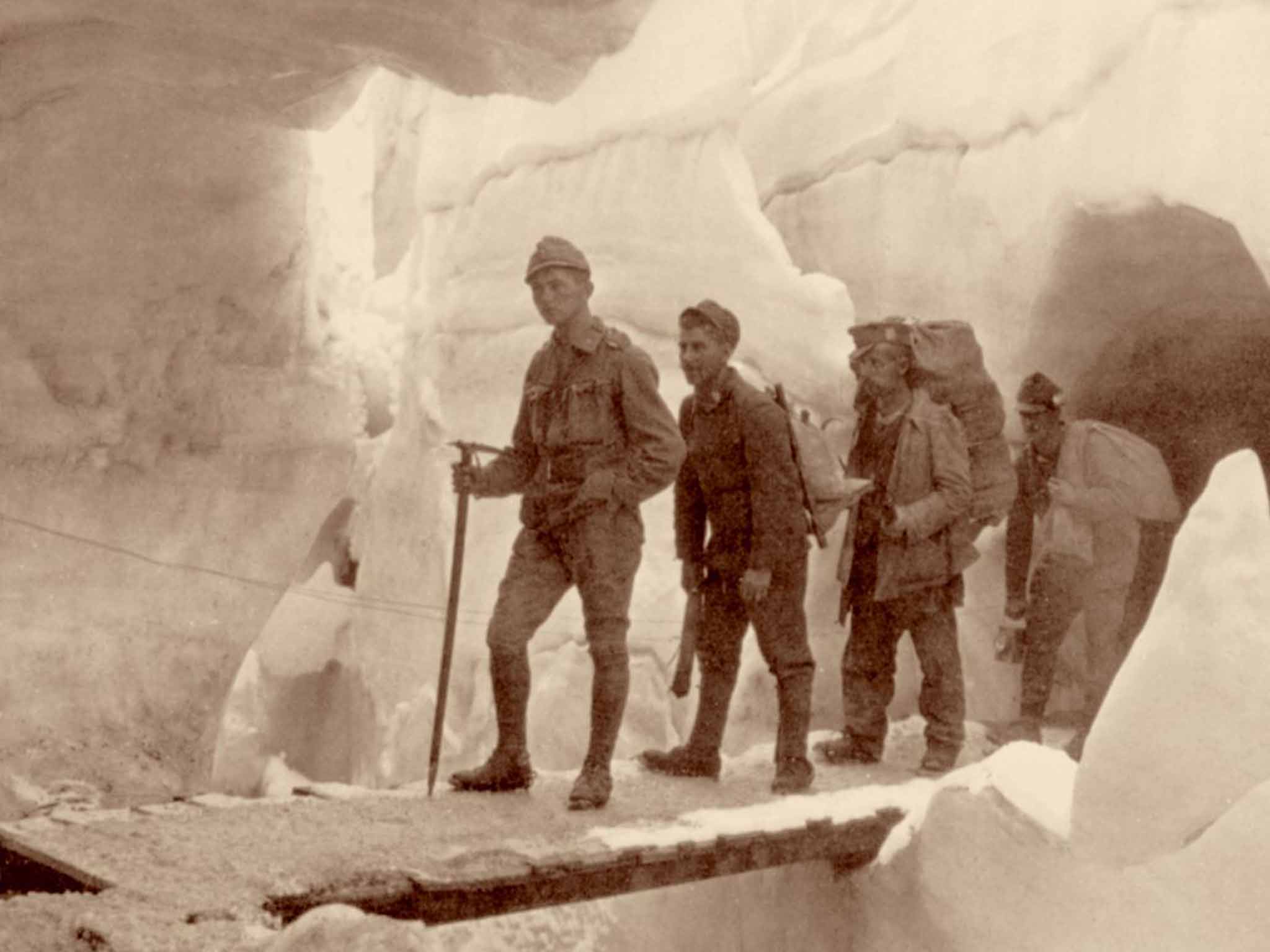

They called it Ice City. Hundreds of Austrian soldiers lived for two and half years inside Marmolada glacier – a 12km labyrinth of caves and tunnels at 3,300m. Barracks, kitchens, first-aid stations, a chapel – all dug up to 60m beneath the ice's surface. Marmolada's Ice City was one of the Great War's iconic theatres, now revealed in the Museum of the First World War located inside the top gondola station. As if this extraordinary feat of warfare and survival weren't enough, the winter of 1916-17 was remarkable – more than 10 metres of snow fell, including four metres in one 48-hour period after which, on what became known as White Friday, an estimated 10,000 soldiers died in avalanches on the Dolomite front.

A century on, the mountains continue to release their secrets. As recently as 2012, the remains of two soldiers were found in the Presena Glacier, around 100km to the west. According to Marcello, September is a good time to find the relics that are reluctantly churned out by melting glaciers.

The next day, with the snowpack at the nine-metre mark and more falling, skiing is superb but plans are being complicated. Our next destination is historic Rifugio Lagazuoi, perched peak-top over the breath-taking Unesco World Heritage mountainscape that stretches from Cortina to Val Badia. Accessed by a rickety red cable car, Lagazuoi is the jump-off point for the scenic Armentarola, the longest piste in the Dolomites, as well as to a labyrinth of still navigable mountain tunnels, dug by the Italians. Sylvester Stallone had better luck with the weather while filming Cliffhanger here: for us, heavy snowpack has rendered the tunnels momentarily inaccessible. Consolation comes in the form of a delicious refuge dinner of venison, polenta and excellent local red wine, served on the precipice of what Italians call "il fronte verticale".

Peace dividends are found at every turn – and not only on skis. The First World War in the Dolomites saw the first widespread use of via ferrata – a system of fixed ladders and ropes built into the rock – to aid the movement of troops. Today, they are a global recreational phenomenon that allow novice alpinists to climb dizzying heights.

Down in the village of Corvara, at the atmospheric Hotel Posta Zirm, hotel patriarch Heinz Kostner guides me through the black and white photos that decorate the cozy Stube, a focal point of the village since 1908. His grandfather, Franz Kostner, personal mountain guide to Prince Arnulf of Bavaria, was present at the battle of Col di Lana as a major in the Kaiserjager.

In a war where men from the same villages and, in some cases, the same families found themselves on opposing sides, one thing shared was respect for the mountains and for what Mark Thompson, author of The White War, called "a third army". Snow.

"On one occasion, my grandfather said, 'Don't put the troops there'. The next day 36 were killed by an avalanche," Heinz recalls. "You may have your enemy in front of you in the mountains, but in an avalanche you may need his help."

After the war, South Tyrol was annexed by Italy, creating a unique blend of Italian, Ladin, and Austrian cultures that bring a punchline to life. "The food is great, the people are funny, and everything works," says Marcello. It is now one of Europe's richest regions.

After four days of superb skiing and spectacular scenery, charming rifugios and mountain restaurants, Marcello delivers me to my final stop, Hotel Ciasa Salares, a four-star den of wine and gastronomy on the outskirts of tiny San Cassiano. It's home to the youngest Michelin-starred chef in Italy, five restaurants and a dedicated chocolate Stube.

Leaving me at the door, he offers a kiss on the cheek and sage words to face the modern South Tyrol menace: "Don't get fat."

Getting there

The Great War Ski Tour is offered by Dolomite Mountains (0844 854 1882; dolomitemountains.com). Starting and finishing in Alta Badia, the four-day guided trip costs from €970 (£715)pp (€870/£641 self-guided). Skiing is lift-service, with some off-piste descents. The prices include three nights' accommodation, lift pass, breakfast, and dinners.

The closest airport with UK links is Innsbruck, served by easyJet (0843 104 5000; easyJet.com) and British Airways (0844 493 0787; ba.com) from Gatwick and Monarch (0871 940 5040; flymonarch.com) from Manchester.

Visiting there

Rifugio Lagazuio (00 39 0436 867303; rifugiolagazuoi.com).

Hotel Posta Zirm (00 39 0471 836175; postazirm.com).

Hotel Ciasa Salares (00 39 0471 84 94 45; ciasasalares.it).

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments