Jackson Hole skiing: The wild Wyoming resort was established 50 years ago

Simon Usborne explores the Rockies' most characterful peaks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You go to Jackson Hole for the skiing and fall in love with the place for the other stuff, like Sunday nights at the Stagecoach. For more than 45 years this out-of-town bar has ended the weekend with “church”, an evening of country music and dancing. Banjo player Bill Briggs hadn't missed a beat, ageing with his bandmates and a good chunk of the congregation. As I watched them dance in pairs through an arch of arms, in their buckled jeans and swirling skirts, a man wearing an oxygen mask rolled through on a mobility scooter.

“You don't miss church!” yelled a guy at the bar in a ten-gallon hat.

In the early days, riders from the old rodeo out back would get into fights at the bar. The band was brought in to provide a distraction; two-stepping was better for business than brawling. Back then Jackson, named after a local beaver trapper, was still a small ranching town. Skiing arrived in the 1930s but not in a big way. Then, in 1965, two skiers with dreams bigger than their pockets threw in a cable car on the other side of the Snake River, where the hills get really big.

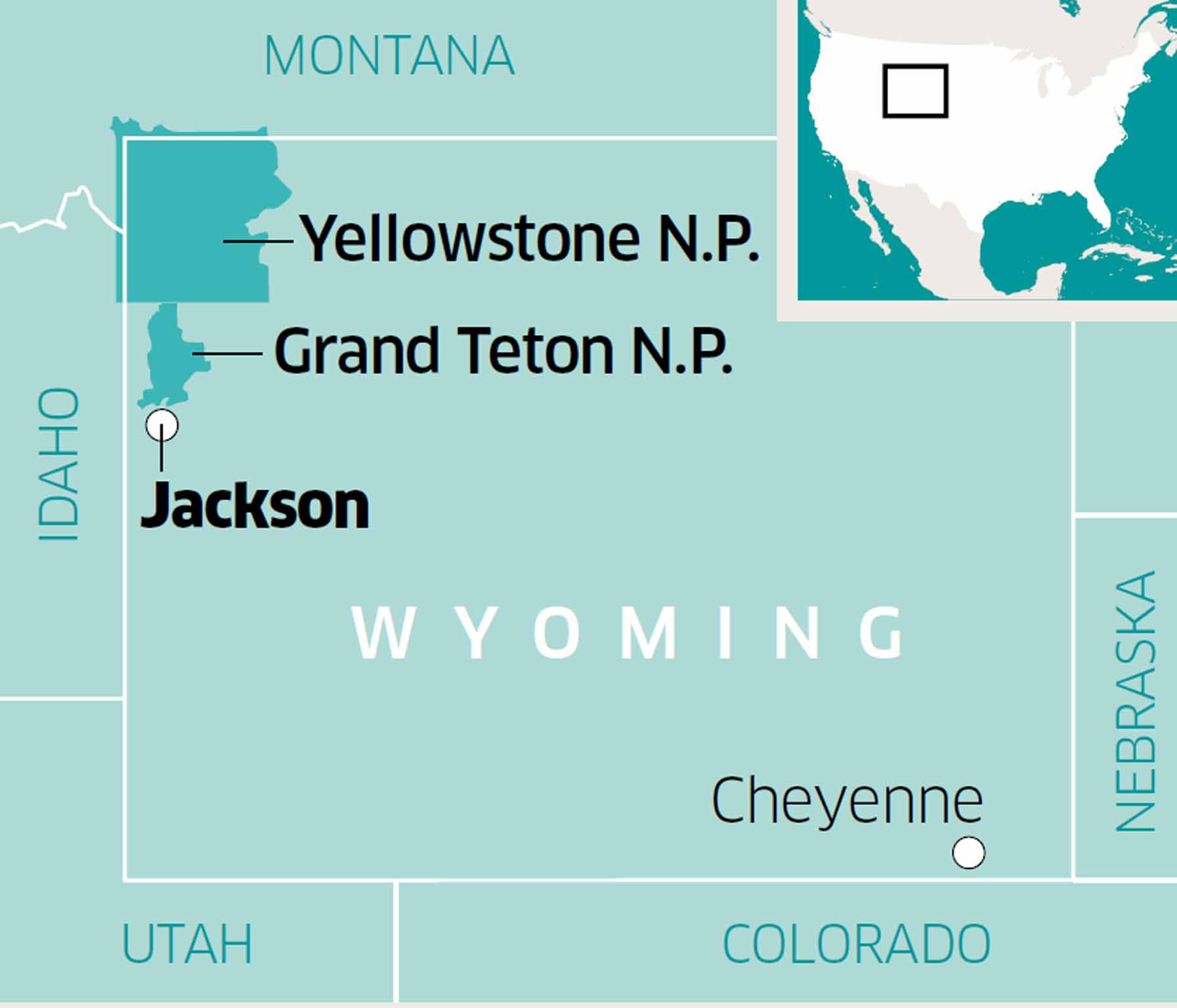

Fifty years later, Jackson and its resort at Teton Village, 25 minutes up the valley in the north-western cowboy state of Wyoming, have become and remain one of the great American winter destinations, where the personalities tower as high as the peaks and, despite considerable development, the founding spirit of the place somehow endures.

Earlier that Sunday in March, as my plane from Chicago dropped into the valley, Grand Teton rose up like a great pyramid, its east face turned golden by the morning sun. The 4,200m peak is the tallest of the toothlike Tetons, a range of the Rockies just south of Yellowstone. And guess who first skied down it, via that same east face? Bill Briggs. When he wasn't playing the banjo, Briggs was a pioneer of American extreme skiing and helped Jackson Hole emerge as its beating heart. In 1971, locals only believed he'd skied the Grand when an aerial photo revealed his tracks.

The resort itself peaks at Rendezvous, at the top of the cable car, or tram as they call it (a shiny new one replaced the original in 2008). You step out a good 1,000 metres lower than the Grand Teton, and some way south, but on to some of the most serious lift-served terrain in North America. Much of the steep stuff is accessible through controlled gates – still rare in typically litigious US resorts. This winter, as part of the half-century celebrations, that access is about to get even better. The Teton chairlift, due to crank into life just before Christmas, opens up the Craggs area formerly accessible only to those willing to hike.

Before helicopter crews spent the summer installing the lift, I walked along Sheridan Ridge to ski the new area knowing that the icy conditions were not favourable. They were worse than that – my descent of the lift's path, high above Teton Village, could only have been less pleasant had the steep ground under my feet been covered in Formica. But I could see the potential even as my eyes shook in their sockets. The snow will be softer when you go. Take the fall-line Kemmerer run, named after the Wyoming coal mining family who have owned the resort since 1992.

I skied for a day with Tommy Moe, one of the dozens of big names who make Jackson what it is. Like all the great resorts, it's the people that make it as much as the mountains, and the roll-call here is among the best anywhere. Moe burst out of Alaska almost unknown in 1994 to stun world skiing with victory in the Olympic downhill in Lillehammer. He visited Jackson not long afterwards and never left, which is a bit of a trend here. He lives near the Stagecoach, in Wilson and works as a resort ambassador and guide for (not inexpensive) hire.

We hiked from the top of the tram, where the scent of hot waffles poured out of Corbet's Cabin, to Four Pines, one of Jackson's most hallowed areas beyond the resort limits. The relative scarcity of snow when I visited (on average Jackson gets way more than most US resorts) meant we had to work hard to make new tracks. Taking a left off Drew's, named after an avalanche survivor once rescued by a dog, Moe lowered me by rope and harness into an unnamed couloir and a stash of undisturbed snow. I got a few turns, the best we'd get that day.

On our next descent from the tram, we paused to peer over the edge of Corbet's Couloir, the resort's notorious chute with its vertical lip and freefall entry. The snow was as hard as the rock walls either side and, after we watched a man with a GoPro and more bravery than skill scrape down and then lose control, we decided to skip it. “We don't want to hurt the journalist,” Moe said as the man's friends lined up to follow him.

Before Moe there was Pepi. Pepi Stiegler won the Olympic slalom at Innsbruck in 1964 and a year later came to Jackson to start the ski school, one of a wave of Austrian racers who taught the US and Canada how to ski. He ran it for almost 30 years and it still works hard to appeal to skiers and families with more grounded ambitions than Corbet's. And despite Jackson's rep, the terrain is here; half of the impeccably groomed runs are for beginners and intermediates. And, as my partner will tell you, the instructors are the friendliest you'll find.

The options multiply off the mountain. I chose to stay half the week in Teton Village, where the hotels and condominiums have mushroomed in the past 50 years around the tram station and the equally uplifting Mangy Moose bar. Don't miss a beer there, or the pizzas at the new Il Villaggio Osteria. And if you want to pay a premium to ski in and out, the Four Seasons is a delight.

Many prefer to stay in Jackson itself, a destination town in its own right linked to Teton by shuttle bus. The main square, with its deer antler arches, leads to boardwalks and sidewalks filled with galleries, gift shops and bars. Have brunch at the cutesy Persephone bakery, dinner at chic The Kitchen, and a beer or more at The Million Dollar Cowboy Bar, an institution made of burled pine with riding saddles for barstools. You can ski in Jackson, too at the steep Snow King Resort and hotel. I enjoyed a fine dinner of elk steak at the revamped Hayden's Post, where Blaze and Kelly, a singing duo over from Boise, Idaho, sang Johnny Cash and Cat Stevens.

To maximise cultural immersion, get on a snowmobile for a dip at Granite Hot Springs. The serene pool in the woods is a boon for aching ski legs, and the powerful machines are a total thrill to drive. In the truck, during my ride out of town with Togwotee Snowmobiling, my guide Mo, a lapsed Mormon who fled Utah for Wyoming in 1978, talked with the other guests – all Americans – about the obscure meats they like. “I luuurve me some gator tail,” said Mo, who added that he once also trapped, skinned and ate a rattlesnake. You just don't get that kind of chat in Les Trois Vallées.

With overdue snowfall forecast before my flight out of Jackon's swish and perfectly formed airport, I was itching to get back on skis. Which brings me to another big character in the 50 years of skiing here. Glenn Exum, the late, great American mountaineer, was all over the Tetons long before the cable car arrived. His company, Exum Guides, remains the town's best outfit for adventure.

I drove north up the valley, past the airport, and into the Grand Teton National Park with Kim Havell, one of Exum's newer recruits. Where the road ends in the winter in the shadow of Grand Teton, we put on climbing skins at Taggart Lake and hiked for almost three hours through the forest. It snowed as we zig- zagged higher and it was tempting to drop down the same way.

We carried on up the ridge and, after a bagel in the shelter of a tree, treaded carefully over some windblown rock into Turkey Chute. We were the only people anywhere near the steep but wide couloir, and the descent was a joy, as old and new snow billowed up to my knees for turn after turn.

Havell is one of the world's top professional freeskiers. She moved here after an itinerant upbringing and 16 years spent working in Telluride, Colorado. Like Pepi, Tommy, Bill and countless other Holers who arrived here in the past 50 years, she could have settled anywhere with good hills and snow. “But this is home now,” she said as we freed our heels again for the walk across the frozen lake to the truck.

Getting there

Simon Usborne flew United Airlines (0845 607 6760; unitedairlines.co.uk) from Heathrow to Jackson, via Chicago. Jackson Hole can also be accessed by British Airways (0344 493 0787; ba.com) and its partner American Airlines, via Dallas, and by Virgin Atlantic (0844 209 7777; virgin-atlantic.com) and its partner Delta, via Atlanta.

Skiing there

Seven-night packages to Jackson Hole start at £732pp including flights and accommodation with American Ski Classics (020 8607 9988; americanskiclassics.com).

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments