The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

I moved to America’s hippest city – this is what they won’t tell you about it…

Hippy, peace-loving Austin, where live music and Mexican food mattered more than politics, sounded like the perfect place in the US to settle, thought Alex Hannaford. But then everything changed

Earlier this month, The New York Times ran a story about American voters planning to leave the United States if their chosen candidate lost the presidential election in November. The newspaper had 2,000 responses to its survey; and a further 3,000 people responded on social media. “Many”, the report read, “said they feared the country might spiral into authoritarianism should Donald Trump win a second term”. Others were deeply concerned about how a Kamala Harris administration would handle the war in Gaza and the economy. There was more general angst – about gun violence, political vitriol, abortion restrictions, rising antisemitism, racism and LGBT+ discrimination.

I moved from London to America in 2003 – into the belly of the beast; deep in the heart of Texas. I’d discovered Austin for myself on a road trip across the States in 1999 and decided I’d one day make it my home. Although Austin, as you may be aware, is known as the “blueberry in the tomato soup”; a puddle of Democratic blue in a sea of Republican red.

I’d joke that whenever anyone in Texas brought up politics, I would reply: “Our Labour party is like your Democratic party,” in an attempt to explain the British political system. “And our Conservative party is like your Democratic party.”

Broadly speaking, then neither of the two main parties in the UK wanted to abolish the NHS, instead seeing “socialised medicine” as it’s pejoratively called in the US, as something Britain should be proud of. (Ignoring, just for a minute, the differences in how much they were prepared to pay for it.)

Neither party made bringing back the death penalty part of their platform. And neither campaigned on the right to bear arms. Gun ownership, meanwhile, was part of the fabric of Texas. And, when I moved there in 2003, Texas was busy carrying out more executions than any other state.

But I had chosen Austin as my home – hippie, peace-loving Austin, where live music and Mexican food mattered more than politics. Guns, immigration, the death penalty, a literal interpretation of the Bible – these were things I was going to be writing about as a journalist, not anything I needed to worry about in the place I now called home. Austin was America’s coolest city: 300 days of sunshine every year; more rivers and lakes and natural springs than I could have imagined; and safe from the excesses of the rest of America. Or so I thought.

Over the 19 years I lived there, I wrote about armed militias, private armies who tasked themselves with preparing to defend Americans against a tyrannical government. I visited death row more times than I can remember, and I witnessed an execution.

I drove the entire length of the US-Mexico border and tracked the bodies of migrants who had died in the desert trying to cross that border. I interviewed school shooters, met cult leaders, and covered the brutal aftermath of hurricanes and tornadoes. I wrote about poverty, violence and wrongful conviction. For one story, I bought a 9mm pistol and described what it was like to become an American gun owner.

But these were all stories. They didn’t affect me or impact my life in any way. I married a Texan and we bought a beautiful house on the outskirts of the city. Our daughter was born there, and we never thought we’d leave. But, over the almost 20 years that I lived there, it had been changing – dramatically. And I didn’t really notice until our daughter started school.

Until this year, Austin had spent more than a decade as the fastest-growing large metro area in the country. The New York Times called its real estate market a “madhouse,” saying it had forced regular people to act like “speculators”. Yet it was the only major growing city in America to have a declining Black population. And it was still trading on its credentials as the “live music capital of the world”, ignoring the fact that by the summer of 2022, an average month’s rent was just under $3,000; working musicians could barely afford to park downtown to unload their gear, let alone live there.

Today, property prices are dropping in Austin. A good thing? Yes. These things go in peaks and troughs. But the ship has sailed; people who could no longer afford to live in Austin have left. There’s no decent public transport system, and residents don’t want their already hefty property taxes to go up any more in order to pay for it.

So what now? A finance professor at the University of Texas recently said if everybody stopped building because things are more expensive, “you could end up in a situation where you are back in the undersupply situation again and rents start rising … if there is no money to be made, no one will build. That is the name of the game”.

Today, 20 per cent of Austin office buildings sit vacant. Covid changed the way we work. No one wants to work full time in an office anymore. It’s too expensive to convert offices into apartments. And meanwhile, Austin’s skyline has changed so dramatically, it’s no longer the instantly recognisable city I discovered back in 1999, distinguished by the dome of its Capitol building, and the slim, 300ft tower on the University of Texas campus.

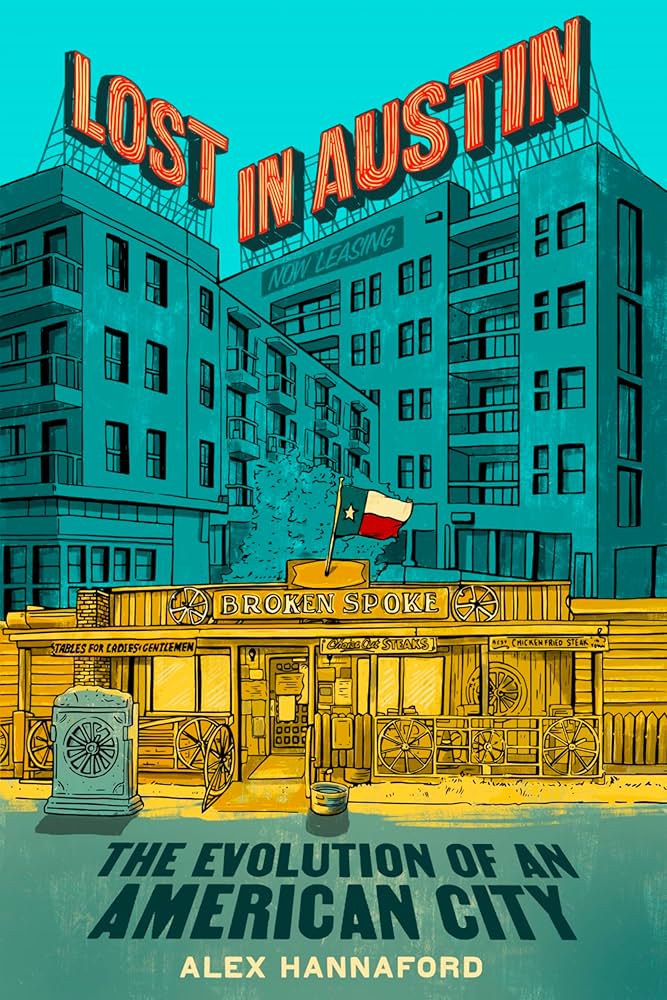

A couple of years ago, while I was back in Austin on a reporting trip for what would become my new book, Lost in Austin: The Evolution of an American City, I met up with my friend Kevin Ashton. Kevin is a fellow Brit and is famous for coining the term “the internet of things” – in which the internet is connected to the physical world.

He’s also the author of a book, How to Fly a Horse, about creativity. After I left Kevin that day, he texted me a picture of what I assumed was Austin. “It’s not Austin. It’s Wuhan in China,” Kevin texted back. Yet the skyline looked so similar – just an empty cluster of steel and glass skyscrapers.

Charles Peveto, the architectural historian for the Texas Historical Commission, asked me which of these many new buildings I thought we might want to put a preservation order on in 50 years’ time. I couldn’t point to any – they were just identical steel and glass. Nondescript. Soulless.

The day our daughter started school in Austin was the day my wife and I began to really talk about guns. She’d been having drills in nursery school, and one day we got an email saying they were having a lockdown but that this time it wasn’t a drill. We later discovered that police had surrounded an apartment complex across the road from the school because of a domestic incident involving a man with a gun.

Now she was in elementary school, and the stories I’d written about school shootings seemed too close to home. Since 2008, Texas has had more school shootings than any other state. 2022 broke the record for the most school shootings across the US in over four decades – 300 shooting incidents nationwide. On 24 May, at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, 19 students and two teachers were killed in a single mass shooting.

In 2016, when our daughter turned five, the state passed a “campus carry” law, which meant anyone over 21 without a felony conviction could carry a concealed handgun on college campuses.

We were in Austin, the hippy outlier yes, but I was profoundly aware that we were subject to the same nutty laws that the State of Texas decided to enact. What’s more, I had come to realise that Austinites weren’t like east or west coast liberals. They were something else entirely – culturally progressive, maybe, but with more of a libertarian persuasion. OK with gay marriage, but they still wanted a Glock 9mm by the bed and an AR-15 in the gun safe downstairs.

In the summer of 2019, we were back in London, my hometown, for a visit, when we read the news that a 23-year-old man had been detained by police in an Austin park. He had a knife strapped to his belt and a 9mm pistol in his waistband and told officers he’d hidden an assault rifle and a 30-round magazine behind some nearby trees. When he was apprehended he was walking towards a group of children playing in the park’s splash pad.

But this wasn’t just any park. This was Pease Park, a few blocks from Pease school, where our daughter went. She’d played in the same splash pad with her friends; we walked our dog in that park; we’d celebrated her birthdays there.

It turned out there was an outstanding arrest warrant for the man with the gun and he’d end up serving five months in jail.

For us, this was the line in the sand. We decided to move to the North East – to New York, a state with stricter gun laws and one where we could enjoy seasons again after years of brutal drought and the hottest summers Austin had ever seen.

We miss our friends in Austin, but we like it here. For us, the outcome of this November’s election won’t change where we live. We’re staying put for now. Our daughter, now 13, is settled in school. She may be half British, but she has an American accent and likes American football (the University of Texas college team, and the Kansas City Chiefs.)

But in five years’ time she’ll be college bound, and we are looking across the Atlantic to England once more. The cost of living has climbed in America, its politics have become crazier in the two-plus decades I’ve lived here, and its healthcare system is governed by profit. England may not be perfect, and I admit I might look back on my life there with rose-tinted glasses, but it’s the people I miss the most. I also want to live in a place where gun violence will never be commonplace.

Lost in Austin: The Evolution of an American City (£23) is available 24 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks