Why more people should visit Eastern Europe

Man Who Pays His Way: Today, the Chisinau Hotel remains resolutely Soviet, with the slogan ‘like visiting your granny, not modern, but clean, warm and relaxing’

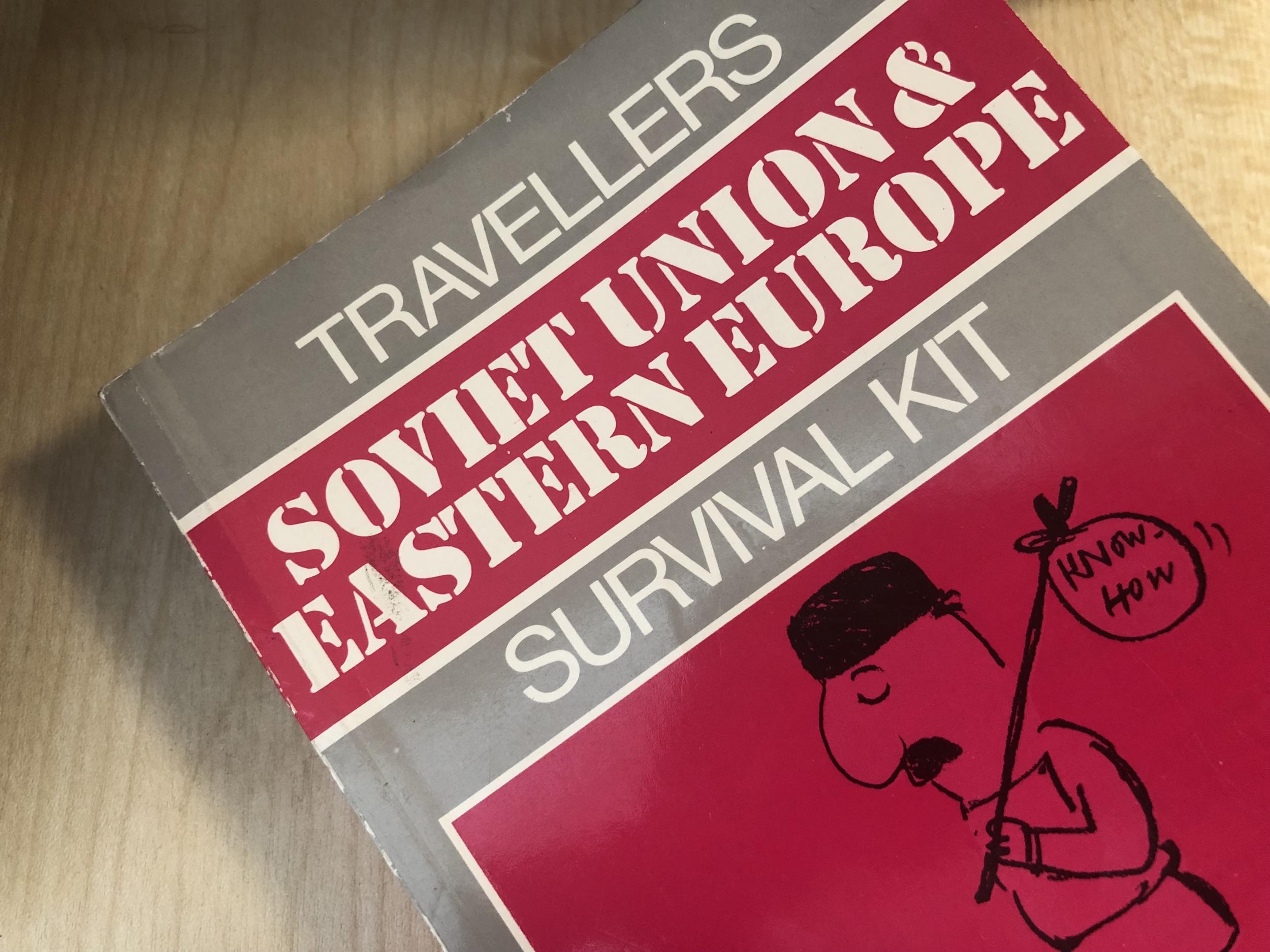

Thirty years ago this weekend, possibly the most ill-timed guidebook in history was published.

Travellers Survival Kit: Soviet Union & Eastern Europe explained in exhaustive detail how to procure a Hungarian visa. But three months after it hit the bookshops, Hungary opened its frontier with Austria and you could walk across the border unchallenged to join the “Pan-European Picnic” outside the town of Sopron.

Conversely and crucially, East Germans on holiday in Hungary could stroll beyond Sopron’s Lenin Boulevard, cross over to Austria and be ushered onto West Germany where citizenship awaited.

Within six months, the Berlin Wall that divided families, street and the world had fallen – rendering the complexities of crossing through Checkpoint Charlie or Friedrichstrasse station between East and West Berlin wonderfully irrelevant.

The Kremlin swiftly lost its grip on the Warsaw Pact nations. And the notion of having a crafty budget holiday behind the Iron Curtain (“Many western visitors subsidise their stay by selling possessions or changing money illegally”) vanished as swiftly as the shady black marketeers, as nations from Bulgaria to Czechoslovakia stopped pretending their currencies were five or 10 times more valuable than the real world believed.

The travel industry was thrilled: surely the collapse of communism would open up the Eastern Bloc from Potsdam to Vladivostok? Richard Branson announced impending beach holidays in the Crimean resort of Yalta.

A few cities – Prague, Budapest and Krakow – have blossomed as tourism hubs. Yet in the past three decades, much of this vast terrain has comprehensively failed to live up to its tourist potential.

Which, along with the welcome untangling of red tape, makes it prime territory for adventure in 2019. So allow me to prescribe a journey to the past which will open your eyes.

Start in southeast Romania, no longer a “dark and troubled land” but ridiculously easy to reach with 14 flights a week from Luton and Liverpool to Iasi. The painted monasteries remain “a stunning sight, the closest things that Romania has to perfection” and woefully unvisited.

Stay in the Hotel Select – a former banker’s mansion converted under communism to accommodation that, it claims, “tourists and locals, people of culture, historians, diplomats and businessmen fully appreciate”.

Frequent absurdly cheap buses run across the border to Moldova, known for centuries as “the land on the route of all disasters”. Chisinau (formerly Kishinev) was a provincial backwater that found itself inadvertently promoted to a capital of one of the USSR’s 15 republics.

Today, the Chisinau Hotel remains resolutely Soviet, with another enticing slogan: “Like visiting your granny, not modern, but clean, warm and relaxing.”

Step aboard a crowded minibus for a ride across what purports to be an international frontier. Not far beyond Chisinau airport, barbed wire and weapons signals the border of the breakaway republic of Transnistria: the one truly Soviet place you can reach without a Russian visa.

You must explain yourself to the frontier officials, who will decide whether to admit you for a full day or only a few hours and stamp your passport accordingly.

Talking of stamps, the Post Office in the self-styled capital of this self-styled nation sells them. But you can only use them to post cards to your friends in Transnistria; the postal service, like the “nation”, is recognised nowhere else.

In the only land which still has the hammer and sickle on its flag, Lenin is revered, and Stalin is given plenty of air at the National United Museum (ask to see the statue of him in the back garden).

Transnistria is in a trance-like state of suspended Soviet animation. At the brand new tourist office, the manager cheerfully admitted to me: “We’re not a very tourist country.”

Beyond another border lies Ukraine, which should be a very tourist country, yet still isn’t. While its Crimean resorts have been annexed by Russia, the jewel of the Black Sea coast – Odessa – is accessible.

“Friendly, relaxed and with an almost southern European air,” was how the 1989 guide describes the city. The palaces, beaches and Potemkin Steps – immortalised in the 1925 film by Sergei Eisenstein – are possibly even less visited than they were back in the USSR days, as the Russian and Belarusan contingents have diverted to Crimea.

“Be prepared to have your preconceptions shattered and to meet people who will convince you that not everything east of the Berlin Wall is sad and shabby.” At least one piece of advice from 1989 still holds good.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks