Can airline darling Southwest recover from a holiday meltdown of its own making?

Simon Calder loves the carrier that Herb Kelleher founded in Texas in 1971. But there are limits

“Accident waiting to happen” is never a good phrase to hear in the context of aviation. But when Southwest Airlines bosses fly to Washington to be grilled by a Senate committee over the most severe aviation disruption since 9/11, they must be expecting to hear those words.

The “bomb cyclone” that hit the US before Christmas brought viciously cold temperatures across much of the continental United States. Extreme weather devastated airline schedules at exactly the time when passengers were most emotionally and financially invested in their journeys.

All the US carriers were affected. On most airlines, though, cancellations were limited to specific locations on the toughest days, and recovery was relatively swift.

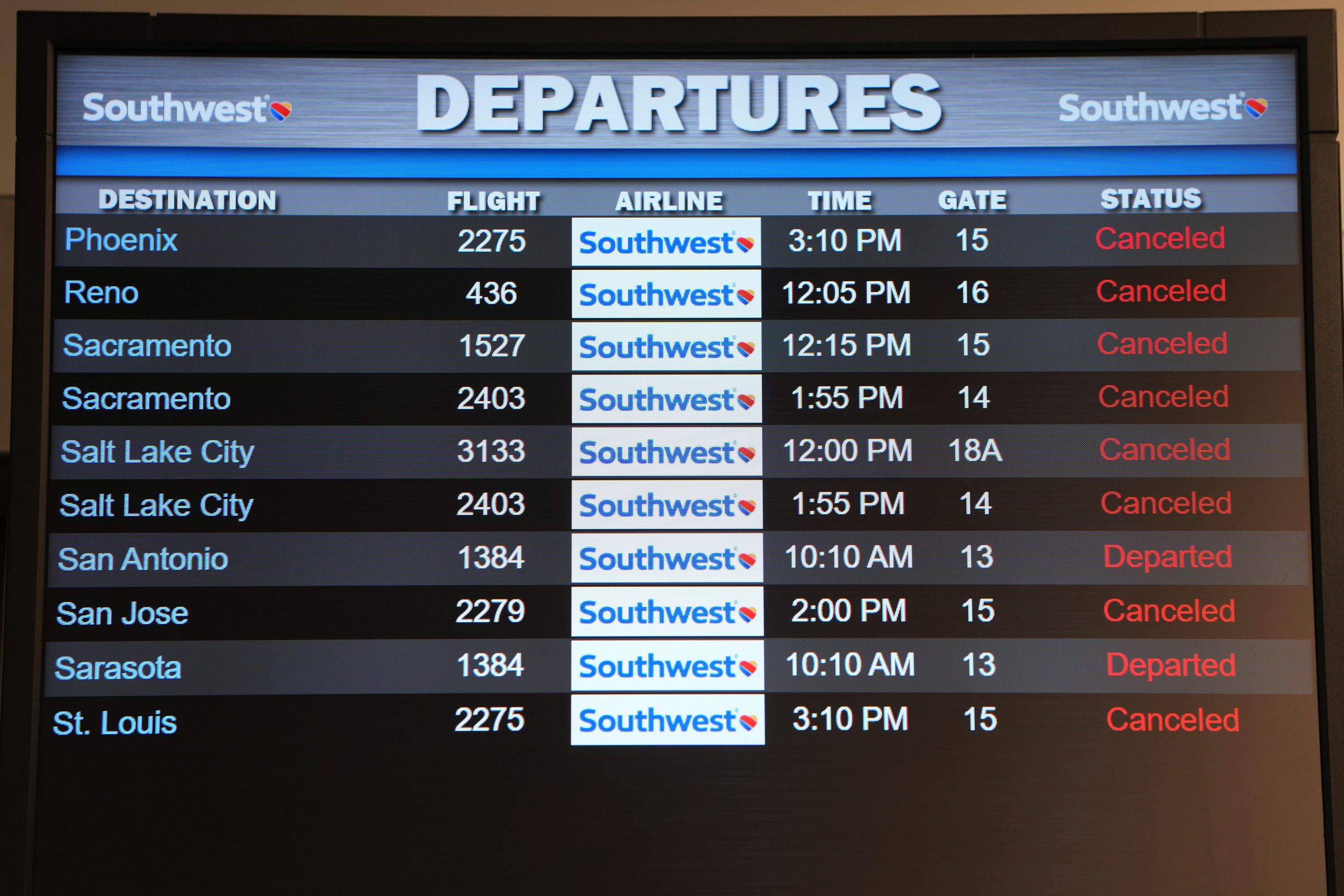

But Southwest Airlines experienced a network-wide collapse that left passengers, pilots and planes even in sunny and warm locations unable to fly because legacy scheduling systems said “no”.

So dysfunctional did the airline become that Southwest had to ground most of its operation for several days while HQ in Dallas desperately sought a reset button to press.

More than 10,000 flights were cancelled, representing over 1.5 million passengers, at a time of year when practically every domestic flight was fully booked, with no seats available. Rental cars sold out, too, with some passengers driving nearly 2,000 miles from Houston in Texas to San Francisco in a desperate two-day bid to get where they needed to be. Whether their baggage might ever catch up with them was another matter.

For years to come, business students will study a systems failure like none other – and one that has trashed the reputation of that rare species, a much-loved airline.

“The problems at Southwest Airlines over the last several days go beyond weather,” says Maria Cantwell, Democrat senator for Washington. She is chair of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, and will be summoning Bob Jordan – chief executive of Southwest – to a hearing. “The committee will be looking into the causes of these disruptions and its impact to consumers,” she says.

From what we know of Senate hearings, Mr Jordan faces ritual humiliation as committee member queue up to lambast his airline for its mistreatment of passengers from their particular home state.

For Southwest, the darling of many American travellers, this is all very new.

Airlines are not usually there to be loved. They exist to provide safe transportation for passengers and returns for their shareholders. By both measures, Southwest has been outstanding since it started flying within Texas in 1971.

Only one passenger has died in an accident involving Southwest, when an engine exploded in flight, shattering a window and dragging Jennifer Riordan half out of the aircraft window. (After that tragedy, Ryanair took the crown for flying the most passengers with no fatalities in accidents.)

Owning shares in airlines is sometimes the preserve of hopeless optimists, but until the coronavirus pandemic Southwest had delivered 47 straight years of profitability – unheard of among major US airlines, most of which have been in Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection (also known as the carwash) while they turn their businesses around. No wonder investors love LUV, as Southwest’s stock exchange listing is known.

Passengers love Southwest, too. Almost always I choose a flight on the grounds of schedule and fare. (Happily, I can take safety for granted.) But there is one airline where I relish the prospect of every journey and will gladly pay a premium to travel on it: Southwest.

My first flight was an all-stations-to-California flight from Chicago Midway via Kansas City and Phoenix to Burbank airport in the northern sprawl of Los Angeles. The fare was $99, less than half the price on the majors, who are now reduced to American, Delta and United.

Since then I have spent thousands more dollars with the airline, and enjoyed every moment. Even in the tragic winter of 2001-2 – after 9/11 and as the aviation world was crumbling – Southwest’s amazing crew were still intent on bringing fun back to flying.

“Place the mask over that big old mouth and nose of yours and breathe like this: aaah, oooh, uuuh,” was the briefing from Duane Redmond aboard Southwest flight 244 in December 2001. “By the way, that wasn’t me calling your house last night,” he added.

And at the end of the flight, he burst into song: “We love you and you love us, we’re so much faster than the bus.

“So come back soon for our hospitality – If you’d married one of us you could have flown for free.”

Duane was channelling the love for an airline that was 30 years earlier by the closest aviation has to a budget airline Messiah: Herb Kelleher.

“He’s the original genius,” Ryanair CEO Michael O’Leary later told me. The Texas lawyer-turned airline boss died four years ago this week, aged 77. But the low-fare model he devised now underpins every successful budget airline. Including Mr O’Leary’s outfit, which is now Europe’s biggest no-frills airline.

The Ryanair boss calls Herb Kelleher “the Thomas Edison of low-fare air travel”.

“This is the guy who created it, this is the guy who first dreamt of charging people $10 for two- and three-hour flights in the US, and he’s the one who revolutionised the industry.”

Kelleher showed O’Leary how to turn around a small and failing airline, and advised easyJet founder Stelios Haji-Ioannou on building a carrier from scratch.

“They were certainly the model on which the European low-cost carriers based their early operations,” says Tim Jeans, former managing director of Monarch Airlines. “Single aircraft type, high utilisation, secondary gateways and simplicity as a byword were central to the success of Ryanair, easyJet and others.

“The failure of first generation of low-cost carriers like Buzz and Debonair can be attributed to the fact that those fundamental principles were not followed.”

The Southwest network began as a triangle of Texas cities: Dallas, Houston and San Antonio. The 1970s comprised the decade of deregulation within the US and across the Atlantic (Freddie Laker, founder of Skytrain, was another Kelleher disciple). But it began slowly, with cheap domestic flights initially permitted only within big states: California and Texas, where Southwest was born.

Free publicity is part of the recipe. In 1992, the lawyer staged an arm-wrestling contest (billed as “Malice in Dallas” to settle a trade-mark dispute. A small aviation supplier challenged Southwest’s right to use the slogan “Plane Smart”; to settle it, the two CEOs hired the Sportatorium Arena in Dallas and lured in the national TV networks. Kelleher lost, but his rival magnanimously agreed to let Southwest continue to use the slogan.

Kelleher also focused ruthlessly on costs – using secondary airports such as Dallas Love Field even after the vast Dallas-Fort Worth hub opened, and Burbank as an alternative to LAX.

Larry Yu, professor of hospitality management at the George Washington University in the US capital, says: “Southwest has been recognised as a game changer for revolutionising the airline services in the world in the last half century.

“There are several Harvard Business cases on Southwest we use in the classroom to discuss how it has gained competitive advantage by differentiation in service and cost as well as effective use of staffing. Up till now.”

Southwest is learning there is definitely such a thing as bad publicity. Running a large airline is an enormously complicated game of three-dimensional chess. Southwest stacks the odds against it with its focus on “line flying”.

Unlike easyJet and Ryanair, crew do not shuttle back and forth to their base each day. Pilots and cabin crew typically make trips lasting several days that can see them zigzagging across North America. The upside: maximising the productivity of staff, at least when things are going well.

But it depends on everything coming together. Once that stops happening, then anything can happen.

“When you’re dealing with sub-zero temperatures, driving winds and ice storms you can’t expect to schedule planes as if every day is a sunny day with moderate temperatures and a gentle breeze,” says Randy Barnes. He is president of the branch of the Transport Workers’ Union representing ground workers at Southwest.

“Many of our people have been forced to work 16-hour or 18-hour days during this holiday season. Our members work hard, they’re dedicated to their jobs, but many are getting sick, and some have experienced frostbite over the past week.”

Evidence of mounting ground-handling problems – and a corporate culture with zero goodwill – emerged before Christmas with the infamous “Denver memo”.

Southwest’s ramp agents – who load and unload bags and prepare aircraft for departure – were sent a warning from their manager, Chris Johnson, headlined “State of Operational Emergency “.

The airline, he writes has “received an unusually high number of absences” – and that will have to stop. Anyone claiming to be sick will need to satisfy “heightened verification of illness”. And if they don’t?

“Failure to comply will be considered insubordination and abuse of sick leave which will result in your termination.” The same punishment awaits anyone refusing to work “mandatory overtime”.

How can a firm that was such a dream to work for that staff would sing on duty turn into an organisation threatening to sack exhausted staff who decline to work beyond their usual hours?

“You have to be relentless in keeping a tight rein on operations and have resilience built in to the flying programme,” says Tim Jeans. “So that a winter storm doesn’t lead to the operation breaking down completely as it has done for Southwest this past week.

“There does seem to be an air of corporate complacency, which has led to the network departing from those early principles and newer, more agile competitors like Spirit and Alaskan stealing their clothes.”

Southwest, once the chippy disruptor, is now part of the aviation establishment. One month from now the lowest fare from Dallas to Chicago is with Frontier at $25, closely followed by Spirit at $30. Southwest is more than twice as much, though in a touching nod at the way we were, you can still check in bags for free.

The ultra-low-cost carriers, like Ryanair and Frontier, seem to have improved on the Southwest model by, for example opening sufficient bases so that all aircraft and crew are back at base each evening – with no exceptions.

Recovery from “Irrops” (IRRegular OPerations) is far easier if you know where your planes and pilots are, and – critically for the flight crew – whether they are within flight time limitations. Checking whether men and women were “legal” became impossible when decades-old systems fell over.

It appears that Denver’s rocky ground operation was “Case Zero” for the infection that spread through Southwest. Once the operation at the Colorado capital began to unravel, it could not be contained. Face with growing mayhem, Southwest’s internal systems went rogue – allegedly cancelling flights with no human intervention, and sending a pilot “deadheading” from Baltimore to Manchester New Hampshire and back without him actually flying a plane.

The jolly Texan giant was beaten by a storm, taking once-loyal passengers with it. Offering frequent flyers 25,000 miles (worth around $300) will not salve the pain felt by passengers stranded overnight at airports with zero communication from a carrier

Can Southwest recover with some of its reputation intact? “Far be it for me to lecture them,” says Tim Jeans, “but ‘back to first principles’ would be a good place to start.

“Holding some senior people to account is important too as there is clearly some disillusionment amongst the workforce.”

Randy Barnes of the Transport Workers’ Union berates the bosses – but points to a possible solution for future violent weather: “If airline managers had planned better, the meltdown we’ve witnessed in recent days could have been lessened or averted. The human factor also has to be a consideration.

“The airline needs to do more to protect its ground crews. Although it can be complicated, especially during the holiday season, we need to consider better spacing of flights during extreme weather events in the bitter cold of winter – as well as the extreme heat of summer.”

Was the Southwest meltdown always an accident waiting to happen? Not necessarily, says Professor Yu of George Washington University.

“This is an example of a low-probability, but high-impact event happening in business operations. It won’t always be going to happen. However, it has a negative impact on the company financially and reputation-wise when it occurs.

“For the long run, Southwest Airlines needs to refresh its brand by investing in technology to improve management systems.

“The damage will be repaired when the airline makes improvements to prevent future low-probability and high-impact events that disrupt normal operations.”

America, the Senate and rival carriers will be watching. And so will I, with the concern of an old friend.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks