Cash and contrition: what is a fair price for flight disruption?

Plane Talk: If airlines want the laws on compensation scrapped, they must be generous

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

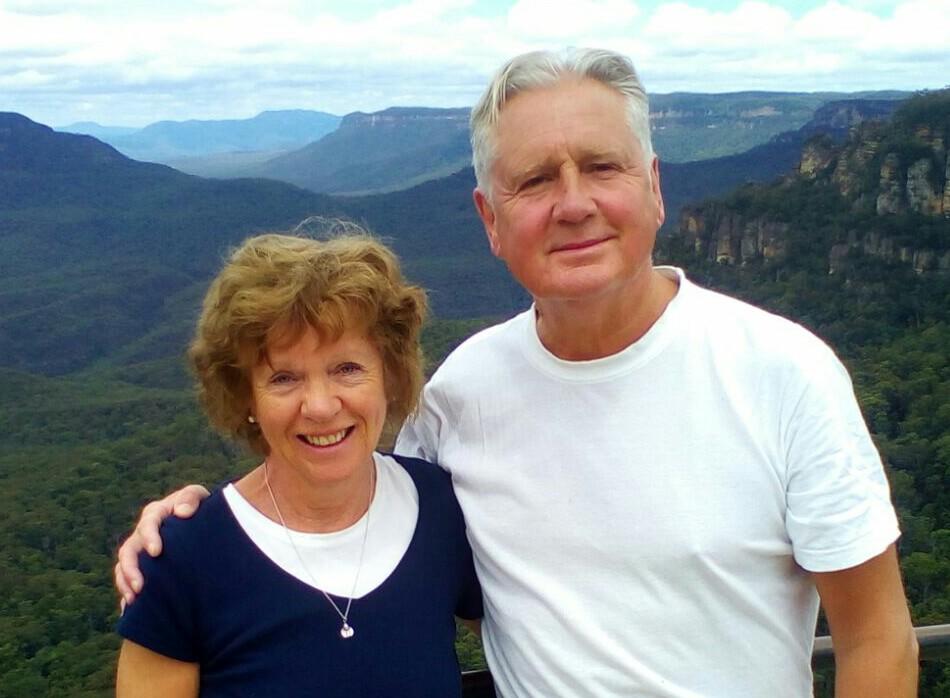

Your support makes all the difference.It was teatime in the UK when Ian Swann contacted me from Christchurch, New Zealand. He and his wife, Jane, had turned up to check in for their Qantas flight to Sydney and onwards to Beijing. They were looking forward to a five-night stay in the Chinese capital, which is now an easy matter thanks to the 144-hour visa-free transit arrangement in a number of cities in the People’s Republic.

If you fly in to China from country A, and depart direct to country B no more than six days later, there is no need to get entangled in the complex and expensive red tape involved in a trip to People’s Republic. The couple’s itinerary on Qantas and Emirates ticked all the boxes.

But the Qantas ground staff at the South Island’s main airport didn’t agree. You need visas, they were told. As you don’t have them, you’re not getting on the flights

Armed with my (evidently not very helpful) interpretation of their situation from the other side of the world, the couple then asked at least to be flown to Sydney, where the Australian airline is based. Mr and Mrs Swann planned to appeal again to Qantas’s better judgment. Had they been allowed on board to Sydney, they surely would have sorted it all out. But again the ground staff at Christchurch said they were going nowhere.

The credit card came in for a beating, buying new flights on Emirates from Christchurch to (ironically) Sydney, to Dubai, and finally back to London. Fifty-four hours, they spent, from checking in on New Zealand’s South Island to getting home to Devon.

The airline confirmed to me that Mr and Mrs Swann had been incorrectly denied travel. Qantas refunded the cost of their new ticket. And it offered compensation for the stress, upset and lost holiday.

Now, if the incident had happened at an EU airport, the starting point for compensation in a denied-boarding case such as this is €600 (£520) per person. That is the minimum payable for a long-haul flight under European passengers’ rights rules.

But Australia and New Zealand have no such generous stipulations. Indeed, under the Qantas conditions of carriage, the Swanns have no automatic right to compensation because the flight wasn’t overbooked; they were denied boarding because of incompetence. In a spirit of generosity, though, the Australian airline offered them £137 each – barely a quarter of what they would have been paid if, for example, a Qantas flight from Heathrow arrived at Singapore four hours late or more.

The ex gratia payment works out at less than a pound for every hour they would have spent in China, or £2.50 for each of those weary, depressing hours of the unexpected journey home.

The derisory offer highlights the random patchwork of compensation rules around the world, most of which do few favours to travellers or the industry.

Europe’s regulations, known as EC261, are absurdly generous to people who are a little bit inconvenienced. On the day the Swanns saw their China holiday shatter, it’s a safe bet that hundreds of other passengers on board at least one long-haul flight from an EU airport (or on a European airline anywhere in the world) qualified for that €600 jackpot after arriving perhaps four, five or six hours behind schedule: annoying, but in the context of a long-haul flight, not really an issue warranting payment of around £100 per hour of delay.

That is a consequence of badly drafted rules which have been reinterpreted by the European Court of Justice, ending up far from the original intention of the regulations – which was to incentivise airlines not to cancel flights abruptly and to be better at handling overbooking.

This weekend, and on many more days between now and the end of the month, it’s a fair bet that tens of thousands of long-haul travellers on Air France will have their travel plans wrecked by continuing strikes.

The French airline can dodge the need to pay compensation by pleading “extraordinary circumstances which could not have been avoided even if all reasonable measures had been taken”. Nonsense, of course; the strikes could have been avoided by the reasonable measure of paying the pilots, cabin crew and ground staff a little more.

When airlines seriously mess up, passengers deserve proportionate compensation, calibrated according to the degree of upset to their travel plans and the fare paid. In the case of Mr and Mrs Swann’s cancelled China holiday, a fair settlement could run to £1,000 or more; for a four-hour delay reaching Singapore on a £500 ticket, £50 looks like a suitable “sorry”.

The International Air Transport Association (Iata), representing the world’s carriers, says the solution is to abolish all mandatory compensation schemes, and instead give passengers “the freedom to choose an airline that corresponds with their desired price and service standards – and ensure that consumers have access to information so they can make informed choices”.

In other words, if protection from disruption is important to you, pay extra for an airline that will look after you when things go wrong. Or take the view that you’d rather countenance the small risk of having to sleep on the floor of the airport in return for a cheaper flight.

A market-based solution has plenty of merit. But for the concept to catch on will require a spirit of generosity on the part of the airlines – for which, after royally messing up Jane and Ian Swann’s plans, Qantas was found wanting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments