Every passport stamp tells a story

The Man Who Pays His Way: Travel options in July 1971 were as wide as the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

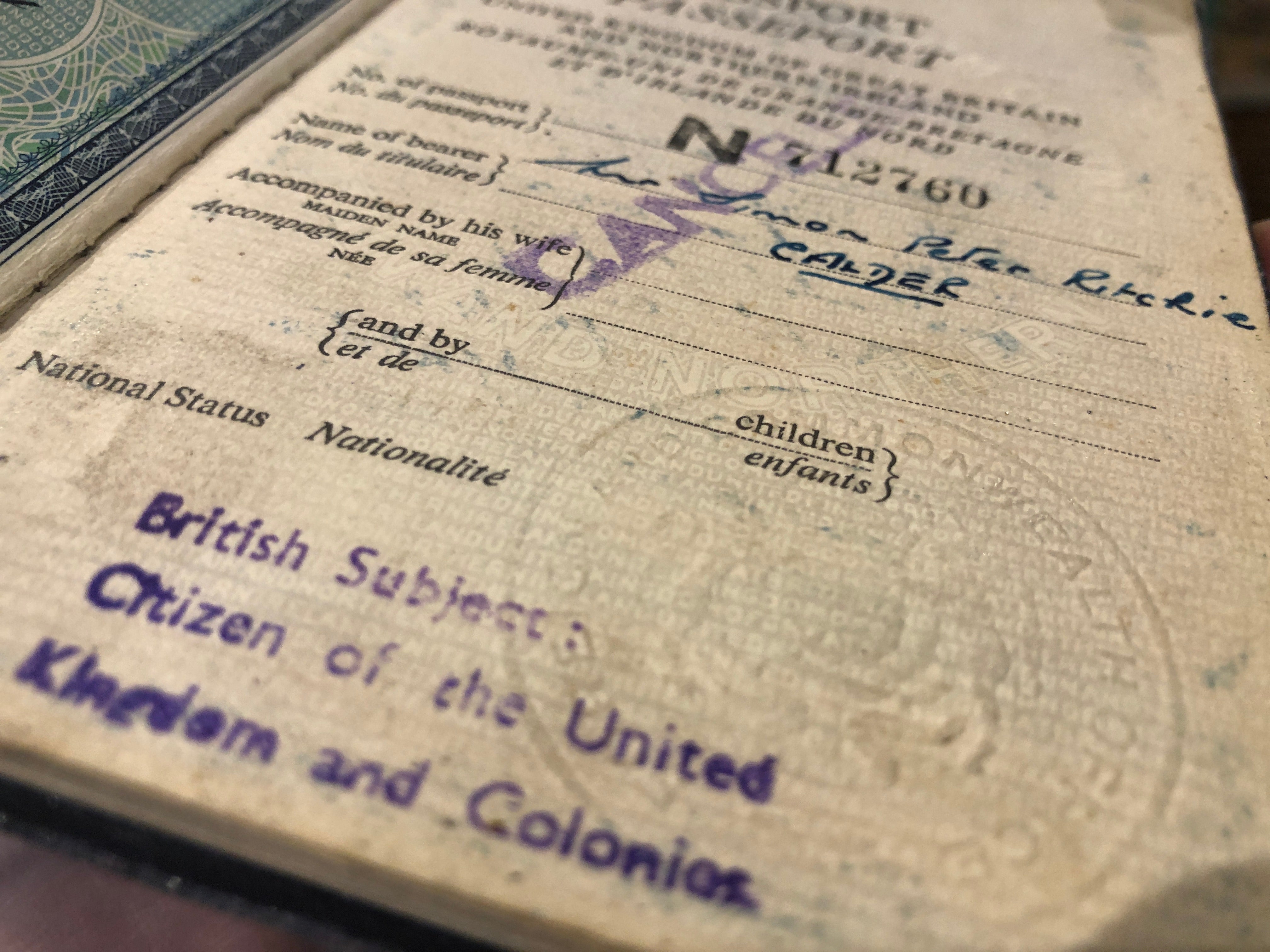

Your support makes all the difference.Half a century old, rather tatty round the edges but full of travel tales. No, not me: my first passport, which was issued 50 years ago this week.

Even before the precious document arrived, I had actually been abroad for a few hours: my school in Sussex gave all pupils the chance to dip a toe in France, with a day trip from Newhaven to Dieppe. Each teacher simply took a list of our names and presented it to the uninterested passport officials.

The dog-eared document declares me to be “A Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies”. Bar the small problem that it cost an absolute fortune to go anywhere more international than Dover, the travel options in July 1971 were as wide as the world.

When “Her Britannic Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs” requested and required, in the name of Her Majesty, to allow the holder of passport N712760 to pass freely without let or hindrance, there was a fair chance that overseas countries would comply.

In July 2021, half the world is off limits to Brits – and anyone with the temerity to want to visit those parts that will let us in faces a battle with bureaucracy (and some serious nasal swabbing) at the end of their meanderings.

All the more reason to leaf through the stiff watermarked pages and to wonder at the wanderings in my first decade of solo international travel.

(In fact, it stretched a further six months: a strike at the Passport Office in the summer of 1981, when I was hoping to renew it, was addressed by giving half a year of extra validity to anyone prepared to queue up at the HQ in Petty France, Westminster.)

The border guards at “Haven Oostende” welcomed me to Belgium, the starting point for many a trip: a ticket issued by the Transalpino agency at Victoria station in London could take the budget traveller onwards by rail to any station in Belgium for £7, which meant almost as far as Aachen in (then) West Germany – whereupon the rail travel ended and the autostop began.

With an overnight ferry across the North Sea and a good run on the autobahn you could make West Berlin by midnight, even allowing for the frontier formalities through the German Democratic Republic – the absurd Soviet puppet state more concisely known as East Germany.

Going deeper into eastern Europe required almost as much pre-planning as a day-trip to France does these days.

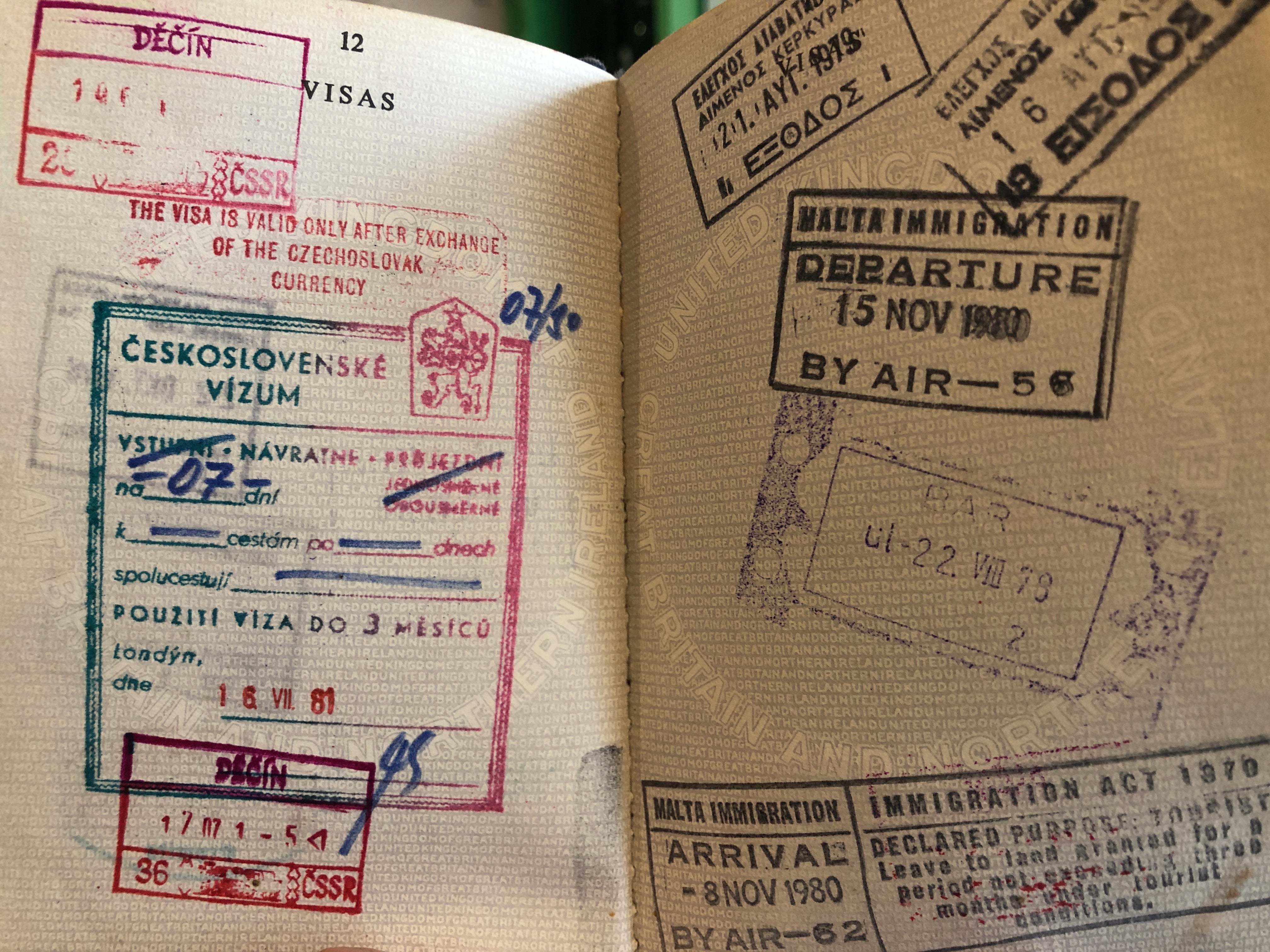

“The visa is valid only after exchange of the Czechoslovak currency,” warns a stern red stamp above a fetching pink and green visa for the nation now split between the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

The grey market for currency in West Berlin was legendary: you could convert a modest amount of sterling into enough soft currency to live like a commissar for weeks. But you also had to change pounds for crowns at an entirely fictitious and unfavourable rate of exchange at a bank in London. And if you were found to have more Czech currency than you could account for, the whole lot would be confiscated and you would be sent packing back to the capitalist West.

On the opposite page, evidence of a trip to Malta on 8 November 1980. The fare, I recall, was more than twice the £26 return that Ryanair was asking for a trip from Birmingham to the island this week. At least I had no worries then about being turned away at the airport for failing to have the right kind of jabs.

The final pages are instructive, too. I see that on 19 July 1972 I declared the export of £30 under the Exchange Control Regulations 1947 – a futile attempt to protect sterling against the ravages of the market. And woe betide any married women thinking of making a break on her own, travelling on what was then a joint passport.

“A passport including particulars of the holder’s wife is not available for the wife’s use when she is travelling alone,” the document warns.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments