MH370: New crash site identified for missing Boeing 777 plane, say scientists

Leading Australian scientists have calculated the crash site 'with unprecedented precision and certainty'

The crash site of Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 is a lonely spot in the southern Indian Ocean, 1,250 miles due west of the southern tip of Western Australia and 2,000 miles south-south-west of Kuala Lumpur - the place where the 239 people on board were last seen alive.

Seven months to the day after the search for the doomed Boeing 777 was officially called off, leading Australian scientists have calculated “with unprecedented precision and certainty” that the plane crashed at a point 35.6 degrees south of the Equator and 92.8 degrees east of Greenwich.

On 8 March 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 departed from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing with 227 passengers and 12 crew. Its disappearance remains the greatest unsolved mystery in aviation. Despite a massive international search effort that lasted almost three years, the only traces of the plane that have turned up are fragments of wreckage washed up on the western shores of the Indian Ocean.

When the transport ministers of Malaysia, Australia and China announced the abandonment of the hunt on 20 January 2017, they said the search had failed “despite every effort using the best science available, cutting edge technology, as well as modelling and advice from highly skilled professionals who are the best in their field.”

But Geoscience Australia researchers re-examined four pictures that were taken by the Airbus Pleiades 1A satellite shortly after start of the hunt, and identified 12 significant pieces of “probably man-made” debris that could be from the lost aircraft - as well as 28 that were “possibly man-made”.

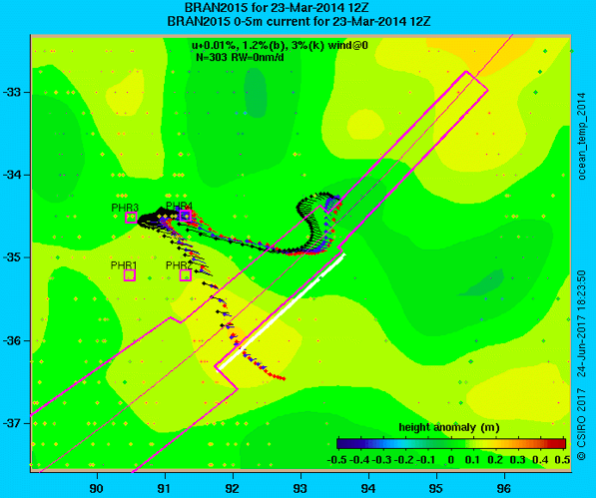

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) conducted tests using a flaperon - the tailplane component which washed ashore on the island of Réunion - to see how it moved in open water subject to wind and ocean currents.

Their report uses new specifications to predict the track taken by the debris, and concludes that the long and expensive search was looking in the wrong place - but the actual crash site was tantalisingly close.

“If we find MH370, which we all hope to do, it will be thanks to all this satellite data,’’ said the lead scientist, Dr David Griffin.

The last contact with flight MH370 took place at 1.19am on 8 March 2014, when Captain Zaharie Shah acknowledged air-traffic control with the words “Good Night Malaysian three-seven-zero”.

No distress messages were sent. It took the airline a further six hours to tell the world that the plane, registration number 9M-MRO, was missing.

An air-sea rescue operation was launched in the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand. But a week after the disappearance, the British company, Inmarsat, showed the jet remained aloft for at least seven hours after the final contact with the flight deck.

Equipment aboard the plane responded automatically to a series of satellite “pings” that allowed investigators to define the path flown by the aircraft south across the Indian Ocean to an area west of Australia, before it was presumed to have run out of fuel and crashed. This is the so-called “Seventh Arc”.

The new report says: “The dimensions of these objects are comparable with some of the debris items that have washed up on African beaches and their location near the 7th arc makes them impossible to ignore.

“If at least some objects in the images are pieces of 9M-MRO, from where did they drift in the weeks between the disappearance of the aircraft and image capture?”

The report said that the 35.6S, 92.8E location was the likely crash site, though two other possible candidates (34.7S, 92.6E and 35.3S, 91.8E) had been identified. All are just outside the search area specified by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau.

The search of the sea bed of the Indian Ocean began in September 2014, intending to identify anomalies that could be larger elements of the 777, such as engines and landing gear.

At the time, Martin Dolan, the bureau’s Chief Commissioner, told The Independent that he expected to find the aircraft within a year, but added “There is no complete guarantee of success.”

The search was called off after covering an area of nearly 50,000 square miles, almost as big as England.

Speculation on the fate of the plane has proliferated since its disappearance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks