How a tragedy at Manchester airport saved hundreds of passengers in the Tokyo plane crash

Lessons learnt after 55 people lost their lives in BA’s last fatal accident four decades ago helped 379 survive in 2024

“As the aircraft stopped, the aft cabin was suddenly filled with thick black smoke which induced panic amongst passengers in that area, with a consequent rapid forward movement down the aisle.

“Many passengers stumbled and collapsed in the aisle, forcing others to go over the seat-backs towards the centre cabin area, which was clear up until the time the right overwing exit was opened.

“A passenger from the front row of seats looked back as he waited to exit the aircraft, and was aware of a mass of people tangled together and struggling in the centre section, apparently incapable of moving forward. He stated ‘people were howling and screaming’.”

That horrifying account of unfolding tragedy is taken from the official report into the last fatal accident involving British Airways.

On 22 August 1985, a Boeing 737 belonging to BA’s charter subsidiary, British Airtours, accelerated along the runway at Manchester airport, destination Corfu. An engine failure started a fire. The pilots aborted the take-off, stopped the plane and ordered an emergency evacuation.

In the ensuing chaos, only 83 of the passengers and crew made it out alive. One initial survivor died six days later, taking the death toll to 55 – most of them killed by a mix of poisonous gases.

“Many survivors from the front six rows of seats described a roll of thick black smoke clinging to the ceiling and moving rapidly forwards along the cabin,” the accident report continues.

“On reaching the forward bulkheads it curled down, began moving aft, lowering and filling the cabin. Some of these passengers became engulfed in the smoke despite their close proximity to the forward exits.

“All described a single breath as burning and painful, immediately causing choking. Some used clothing or hands over their mouths in an attempt to filter the smoke; others attempted to hold their breath. They experienced drowsiness and disorientation, and were forced to feel their way along the seat rows towards the exits, whilst being jostled and pushed.”

Almost 40 years later, on 2 January 2024, a Japan Airlines Airbus A350 was cleared to land on runway 34R at Tokyo’s main airport, Haneda. A small Dash-8 propeller plane belonging to the Japanese coastguard had been told to hold short of the runway but – we now know from the release of air-traffic control messages – strayed onto it.

“It seems to be that the guy in the Dash-8 lined up without permission,” says Rowland Burley, a former Cathay Pacific Boeing 747 pilot who has flown into Haneda many times.

“I understand he’d been taxiing for an hour already, so he was probably impatient to be off – very ‘go minded’. It’s just weird that he didn’t look up and see this large A350 coming in and about to land on top of him.

“It’s just so sad that at night the A350 pilots didn’t actually see this guy in front of them.

“I can understand that because there’s lots of lights around, it’s very bright, you’ve got the city quite close and Yokohama [a large port] and stuff, so there would be a lot of confusion with other lights around.”

The Japan Airlines A350 struck the Dash-8, and both aircraft caught fire. The captain of the coastguard plane escaped, but his five colleagues perished.

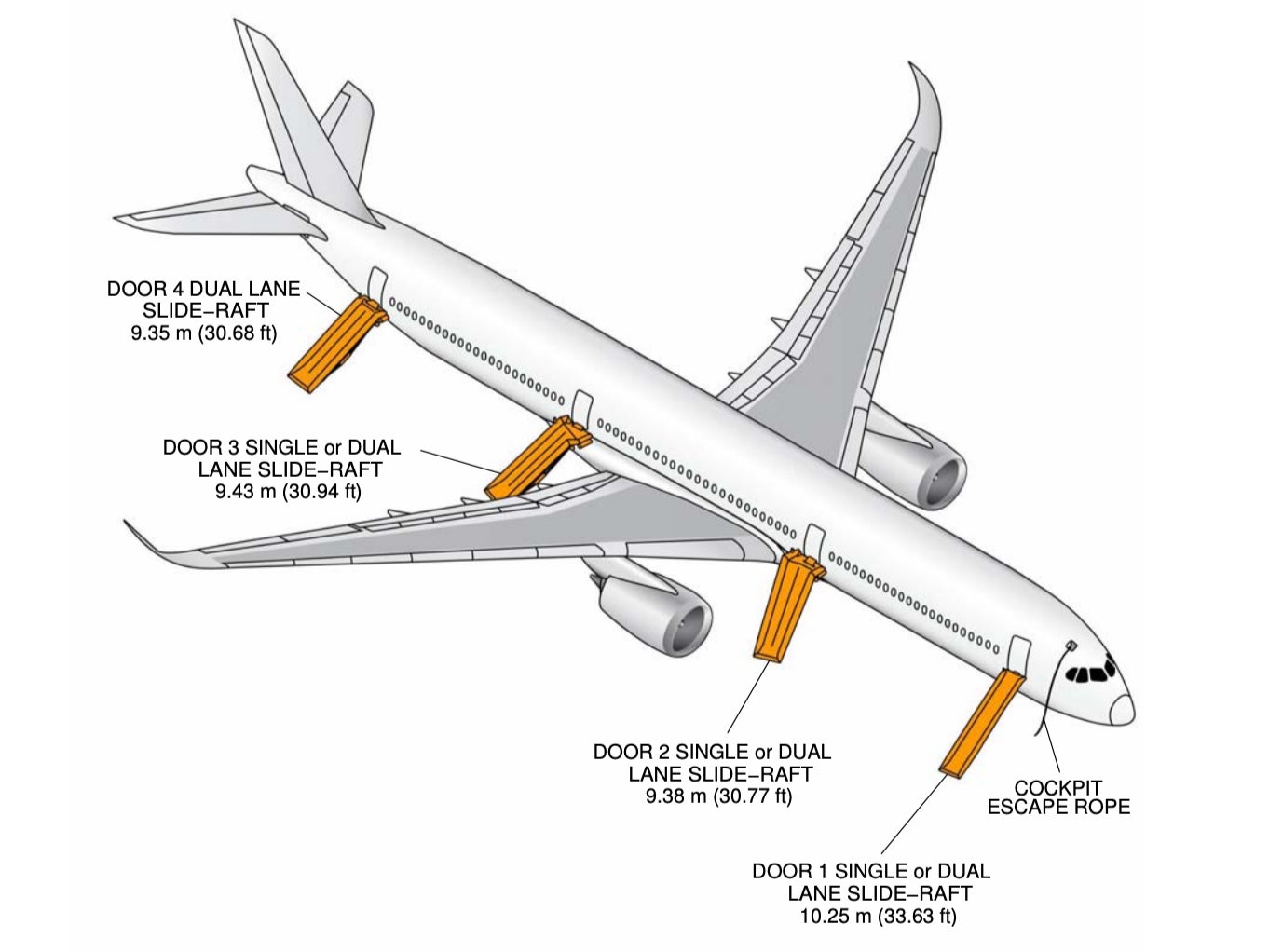

The passenger jet continued for 1km along the runway, in flames. On board: 367 passengers, including eight infants under two, and 12 crew. The public address system failed, meaning cabin crew had to shout and use megaphones to order the evacuation. Only three of the eight emergency slides could be used because of the fire engulfing much of the aircraft.

The circumstances so far bear a strong resemblance to the British Airtours tragedy at Manchester, but with nearly three times as many people at risk.

Yet all 379 people escaped from the aircraft. In terms of physical injury, there was nothing worse than bruises; the emotional toll of being involved in a near-death experience can only be imagined.

The Manchester disaster helped save their lives. Airlines are ferociously competitive – except in the most important aspect of all: safety. The aviation industry is based on open, collaborative investigation. The imperative is not to apportion blame but to protect future passengers by learning from tragedy.

The loss of 55 souls in chaotic circumstances in Manchester changed much. Floor lighting to guide passengers to an exit is mandatory. At those exits, minimum space and handholds are stipulated for cabin crew so they can help passengers escape.

At Manchester, the cabin crew – including two young stewardesses who perished while striving to save lives – performed their duties in exemplary fashion. But they had been dealt a deadly hand: on a blazing aircraft, filling with lethal fumes, passengers became jammed together at exits and the crew could not physically extract people in time.

While the Boeing 737 had been certified for evacuation within 90 seconds, events at Manchester bore no resemblance to the test parameters.

Passengers in the overwing exits did not understand how to open the emergency hatch, nor what to do with the heavy slab of metal when finally it was open. Today, everyone enjoying the extra legroom will also get a lecture about how to handle the device – and asked if they are prepared to assist.

The odds of a typical crew member experiencing an emergency evacuation during the course of a career are extremely low. Chris Hammond worked as a pilot for 43 years, first for BA’s predecessor BOAC and later as a captain for easyJet.

He now speaks for the British Airline Pilots’ Association (Balpa).

“I had probably three or four incidents that could have turned into an evacuation if they’d gone wrong. They didn’t,” Captain Hammond says.

“I’ve never, ever had to push the button to evacuate.

“There is a button, yes – it’s on the overhead console. The evacuation button starts off all kinds of sirens and so forth and indicates to the cabin crew that they can do their drills.

“We would announce if we could from the flight deck, saying: ‘This is the captain. This is an emergency. Evacuate, evacuate.’

“The cabin crew can initiate an evacuation themselves. If they don’t hear from the front end, that could be because the front end are disabled, so it’s within their remit to start one themselves.”

Cabin crew’s focus is on helping passengers survive survivable accidents.

The nice person who poured you a drink and joked with you? They just turned into Gunnery Hartman from Full Metal Jacket.

So says a wise old aircraft captain who goes by the handle of KC-10 Driver (translation: pilot for the military version of the McDonnell Douglas DC-10). He posted a thread on X, formerly Twitter, that sums up an emergency evacuation. The cabin crew, he says, are trained to shout at passengers to save lives.

“You’ll obey. There is no ‘what if I don’t?’ You’ll move quickly, because they’re using psychological means to get you to move. If you stop at the slide, they’re not going to have a conversation with you. You’re going down the slide and quickly. They’ll evacuate everyone within 90 seconds.

“You may end up injured at the bottom of the slide, but it’s better than burning.”

The 379 passengers and crew did not burn, but their £100m aircraft did. “We love our jets, but they exist to deliver us to a destination,” says KC-10 Driver.

“They’re engineered to sacrifice themselves to protect you if need arises and let you escape quickly.”

The morning after the nightmare landing, almost nothing remained of the sacrificed carcass of the Airbus A350. The fuselage is made from carbon-based composite – used for high strength, low weight and durability. And, it turns out, added safety.

The US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) says: “Aluminium will melt at 660C in large fires. Typically, for a composite material, the degradation temperature to cause burning is 300-500C, but it will maintain structural integrity during burning.”

Investigators are now trawling through the embers looking for the “black box” – the cockpit voice recorder, which will reveal how the pilots responded. Perhaps a year from now, the final report into the accident will tell the full, chilling story. Safety officers for the world’s airlines will read it closely.

“The safety and security of our customers and crew will always be our number one priority and we continually review our procedures in line with best practice and events that occur globally in our industry,” says a Virgin Atlantic spokesperson.

“Once the final report is produced by the Japanese Transport Safety Board we will review and, if applicable, take onboard any learnings.”

Before then, though, passenger behaviour should start to change, says Chris Hammond of Balpa. He says that pilots will be “emphasising that the safety briefing must be watched” – perhaps by saying: “These things can happen. If you don’t believe me, remember the Japanese flight.”

The survival of everyone on the passenger jet was not, though, a miracle. It was a testament to rigorous training and a safety culture unmatched in any other industry. British Airways has had an outstanding safety record since the Manchester disaster, and its rivals – Virgin Atlantic, easyJet, Jet2 and Ryanair – have suffered no fatal accidents.

Out of tragedy, safety.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks