French air-traffic control strike: The impact on the environment and economy when flights are diverted

Plane Talk: The convoluted routes aircraft take to avoid the strike zone is like going back in time to the Cold War

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Early in 1989, flying over the bleak, bitter Deutsche Demokratische Republik on a flight to West Berlin, I tried to explain to a fellow passenger the complexities of Cold War geography. The West Germany-East Germany split was clear enough: a vicious frontier splitting the nation, dividing the democratic German Federal Republic from the undemocratic German Democratic Republic (DDR).

But buried deep within the latter was our destination. West Berlin was a fragment of West Germany entirely surrounded by East German territory — and much closer to Poland than to Munich, Frankfurt or Hamburg.

The city’s lifelines were the air corridors from West Germany: narrow, low-altitude tracks. There were no “sky maps” in those days to let you view your progress, but it didn’t matter: as the plane approached the East German frontier it descended to 10,000 feet for the final 100 miles to West Berlin.

We were flying from Frankfurt on Pan Am, though other possibilities were Air France from Stuttgart or British Airways from Cologne. Following the post-war carve up of Germany, only airlines from the victorious allies were allowed to fly between the West and Berlin.

Even after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the aeronautical shenanigans continued. In February 1990, three months after the fall of the Wall, the West German leader and father of detente, Willy Brandt, flew from Frankfurt to the newly formed Social Democrats’ congress in Leipzig.

The two countries were still separate, and German planes were not allowed to fly direct from West Germany to East Germany, so the Lufthansa jet flew south to Basel, touched Swiss airspace and then threw a U-turn to fly north-east into DDR territory.

Today, Lufthansa can fly wherever it wishes, but non-German carriers still compete ferociously to Berlin, in the shape of easyJet of Britain, Ryanair of Ireland and Norwegian. I happened this week to be flying on Norwegian from Gatwick to Berlin.

Everyone was on board in good time, but we then had to wait half-an-hour for an air-traffic control slot. The cause: the first (and almost certainly not the last) French controllers’ strike of the year, which ran from Monday to Friday.

Air-traffic control centres in Brest, Bordeaux and Aix-en-Provence were affected. Flying between the UK and Germany takes you nowhere remotely near any of these, but the reverberations of the strike strayed way beyond France.

To avoid French airspace, airlines filed flight plans which, in a normal week, would have been regarded as deranged: Frankfurt to Lisbon via Essex and Cornwall, and the Canaries to Copenhagen via Wales.

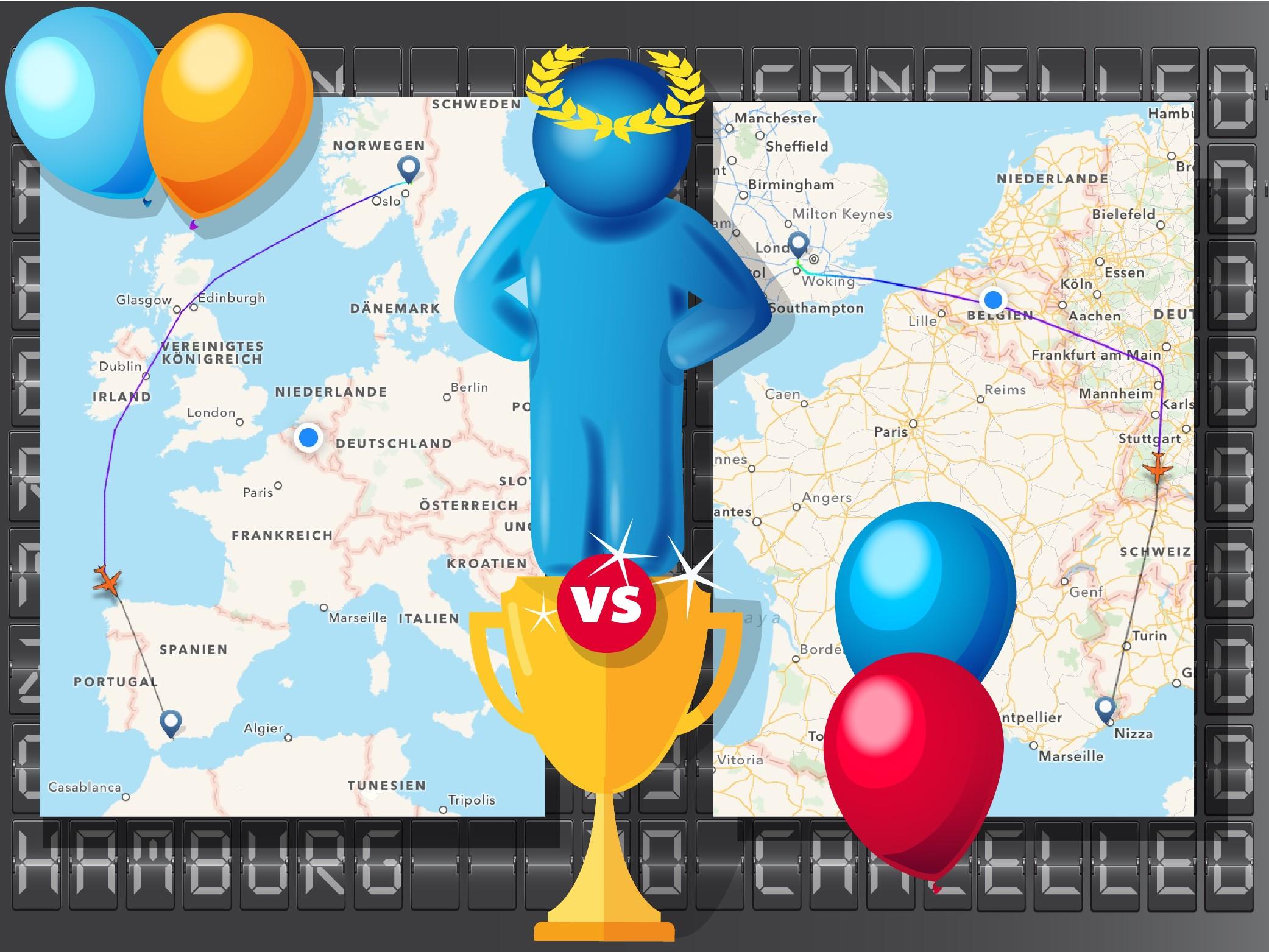

So enraged was Aage Dünhaupt, head of communications of the Airlines For Europe group, that he concocted a new award called an Alfie, for the most extreme diversion of the week. An Oslo-Malaga flight that took in Glasgow, Dublin and Cork was a contender, but clear winner was the Gatwick-Nice flight that wandered almost as far east as the Iron Curtain, overflying Heidelberg – about 400 miles away from the direct track.

The airline was prepared to spend a fortune on fuel and overflying payments, in order to avoid the more onerous costs of a cancellation and, of course, to make sure its passengers were where they wanted to be, if not when. The passengers were no doubt annoyed to spend an extra hour or more in the air, but glad not to be among the 30,000 or so travellers who had their plans wrecked by the strike; around 2,000 flights were cancelled.

The right of air-traffic controllers to strike is sacrosanct, but before the next round of disruption one or two of them might want to take a moment to contemplate the damage their action causes. The environment takes a hammering.

Even though there are fewer flights, those that operate are likely to be burning more fuel on longer routings or while waiting to take off or land. Airlines suffer, of course, but the business impact goes much deeper: by destroying thousands of Mediterranean holidays, the strikers are damaging employment prospects in a part of Europe desperately in need of work.

Football matches and funerals were missed and cannot be replayed. Add in the family feasts and amorous assignments that were wiped out, and strike-hit days in 2017 looks about as joyless as life back in the DDR.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments