Kabul's women find power and liberation in the city's vibrant cafes

In an Islamic culture that still dictates how they should dress and interact with men, women can express themselves freely in the Afghan capital’s coffee shops, find David Zucchino and Fatima Faizi

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On some days, life as a young woman in Kabul can feel suffocating for Hadis Lessani Delijam, a 17-year-old high school senior.

Once, a man on the street harangued her for her makeup and western clothes; they are shameful, he bellowed. A middle-aged woman cursed her for strolling and chatting with a young man.

“She called me things that are so terrible I can’t repeat them,” Delijam says.

For solace, Delijam retreats to an unlikely venue – the humble coffee shop.

“This is the only place where I can relax and feel free, even if it’s only for a few hours,” Delijam said recently as she sat at a coffee shop, her hair uncovered, and chatted with two young men.

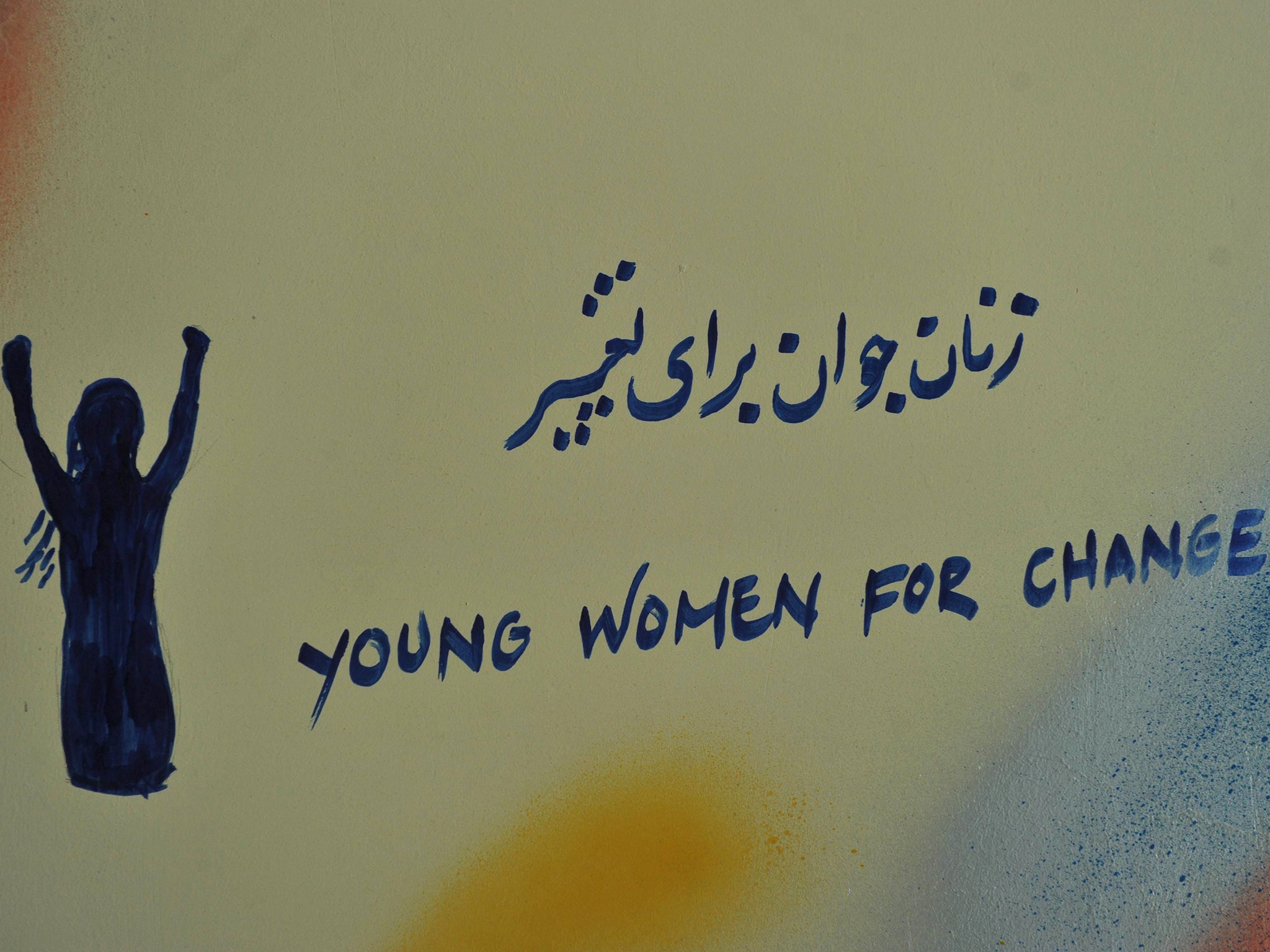

Trendy new cafes have sprung up across Kabul in the past three years, evolving into emblems of women’s progress.

The cafes are sanctuaries for women in an Islamic culture that still dictates how they should dress, behave in public and interact with men. Those traditions endure 18 years after the toppling of the Taliban, who banned girls’ education, confined women to their homes and forced them to wear burqas in public.

These days, conversations at the cafes often turn to the Afghan peace talks in Doha, Qatar, between the United States and the Taliban. Many women worry their rights will be bargained away under pressure from the fundamentalist, all-male Taliban delegation.

“We are so frightened,” says Maryam Ghulam Ali, 28, an artist who was sharing chocolate cake with a friend at a coffee shop called Simple. “We ask each other what will happen to women if the Taliban come back.”

“When we come to cafes, we feel liberated,” she added. “No one forces us to put on our headscarves.”

Many young women in Kabul’s emerging cafe society were infants under Taliban rule. Delijam had not yet been born. They have come of age during the post-Taliban struggle by many young Afghans to break free of the harsh contours of a patriarchal society.

I don’t want to be recognised as someone’s sister or daughter, I want to be recognised as a human being

The women have grown up with mobile phones, social media and the right to express themselves freely. They cannot imagine returning to the puritanical dictates of the Taliban, who sometimes stoned women to death on suspicion of adultery – and still do in areas they control.

Farahnaz Forotan, 26, a journalist and coffee shop regular, has created a social media campaign, #myredline, that implores women to stand up for their rights. Her Facebook page is studded with photos of herself inside coffee shops, symbols of her own red line.

“Going to a cafe and talking with friends brings me great happiness,” Forotan said as she sat inside a Kabul coffee shop. “I refuse to sacrifice it.”

But those freedoms could disappear if the peace talks bring the Taliban back into government, she said.

“I don’t want to be recognised as someone’s sister or daughter,” she said. “I want to be recognised as a human being.”

Beyond cafe walls, progress is painfully slow.

“Even today, we can’t walk on the streets without being harassed,” Forotan said. “People call us prostitutes, westernised, from the ‘democracy generation.’”

Afghanistan is consistently ranked the worst, or among the worst, countries for women.

One Afghan tradition dictates that single women belong to their fathers and married women to their husbands. Arranged marriages are common, often to a cousin or other relative.

In the countryside, young girls are sold as brides to older men. Honour killings – women killed by male relatives for contact with an unapproved male – still occur. Protections provided by the Afghan Constitution and a landmark 2009 women’s rights law are not always rigorously enforced.

In 2014, the Taliban launched a series of attacks against cafes and restaurants in Kabul, including a suicide bombing and gunfire that killed 21 customers at the popular Taverna du Liban cafe, where alcohol was served, and Afghan men and women mingled among westerners.

Afterward, the government forced a host of cafes and guesthouses to shut down for fear they would draw more violence.

Human instinct is as powerful as religion – the need to connect, to share and love, to make eye contact, is instinctual

For the next two years, much of westernised social life in Kabul moved to private homes. But in 2016, new coffee shops began to open, catering to young women and men eager to mingle in public again.

Still, except for urban outposts like Kabul, Herat and Mazar-e-Sharif, there are few cafes in Afghanistan where women can mingle with men. Most restaurants reserve their main rooms for men and set aside secluded “family” sections for women and children.

That is why the Kabul cafes are so treasured by Afghan women, who seek kindred souls there.

“Human instinct is as powerful as religion,” said Fereshta Kazemi, an Afghan-American actress and development executive who often frequents Kabul coffee shops.

“The need to connect, to share and love, to make eye contact, is instinctual,” she said.

After the Taliban fell in 2001, those instincts were nurtured as girls and women in Kabul began attending schools and universities, working beside men in private and government jobs, and living alone or with friends in apartments. The Afghan Constitution reserves 68 out of 250 seats for women, at least two women from each of 34 provinces.

Protecting those achievements dominates cafe conversation.

Mina Rezaee, 30, who opened the Simple coffee shop in Kabul a year ago, makes sure no one harasses her female customers for wearing trendy clothes or sitting with men.

“Women make the culture here, not men,” she said.

She gestured to a table where several women, their headscarves removed, sat laughing and talking with young men.

“Look at them – I love it,” Rezaee said. “It’s the Taliban who needs to change their ideology, not us. That’s my red line.”

Tahira Mohammadzai, 19, was an infant in the southern city of Kandahar, the Taliban headquarters, when the militants ruled Afghanistan. Her family fled to Iran and returned seven years ago to Kabul, where she is a university student.

“I heard stories from my mother about how different life was then,” she said at the Jackson coffee shop, named for Michael Jackson. “It’s impossible now to go back to the way things were.”

I wish there was a cafe full of male politicians who had one priority — peace

Her red line? She said she would rather continue living with the war, now in its 18th year, than face a postwar government that included the Taliban.

“If they come back, I’ll be the first one to flee Afghanistan,” Mohammadzai said.

Forotan, the #myredline founder, said she was determined to stay no matter what happens. Relaxing inside the coffee shop, her short dark hair uncovered, she longed for another type of cafe.

“I wish there was a cafe full of male politicians who had one priority – peace,” she says.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments