Jingdezhen, China: The birthplace of a nation and its ‘white gold’

Changan’s porcelain was so valuable that the town’s name took on great significance

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s Saturday morning and the town’s creatives are packed into a large courtyard. At row after row of tented stalls, young designers sell their creations, from elegant tea sets to hand-painted ceramic earrings. I could be in east London, that is, until regimented tones of Mandarin remind me I’m in Jingdezhen, a third-tier Chinese city.

The term “Made in China” typically brings to mind poor-quality knock-offs, but that wasn’t always so. Centuries ago, China was the world’s artistic superpower, renowned for exquisite, artisanal wares. When Europeans first saw Chinese porcelain, for example, it seemed so fine, translucent and superior to anything they could fashion that they concluded it must have been made with magic and called it “white gold”.

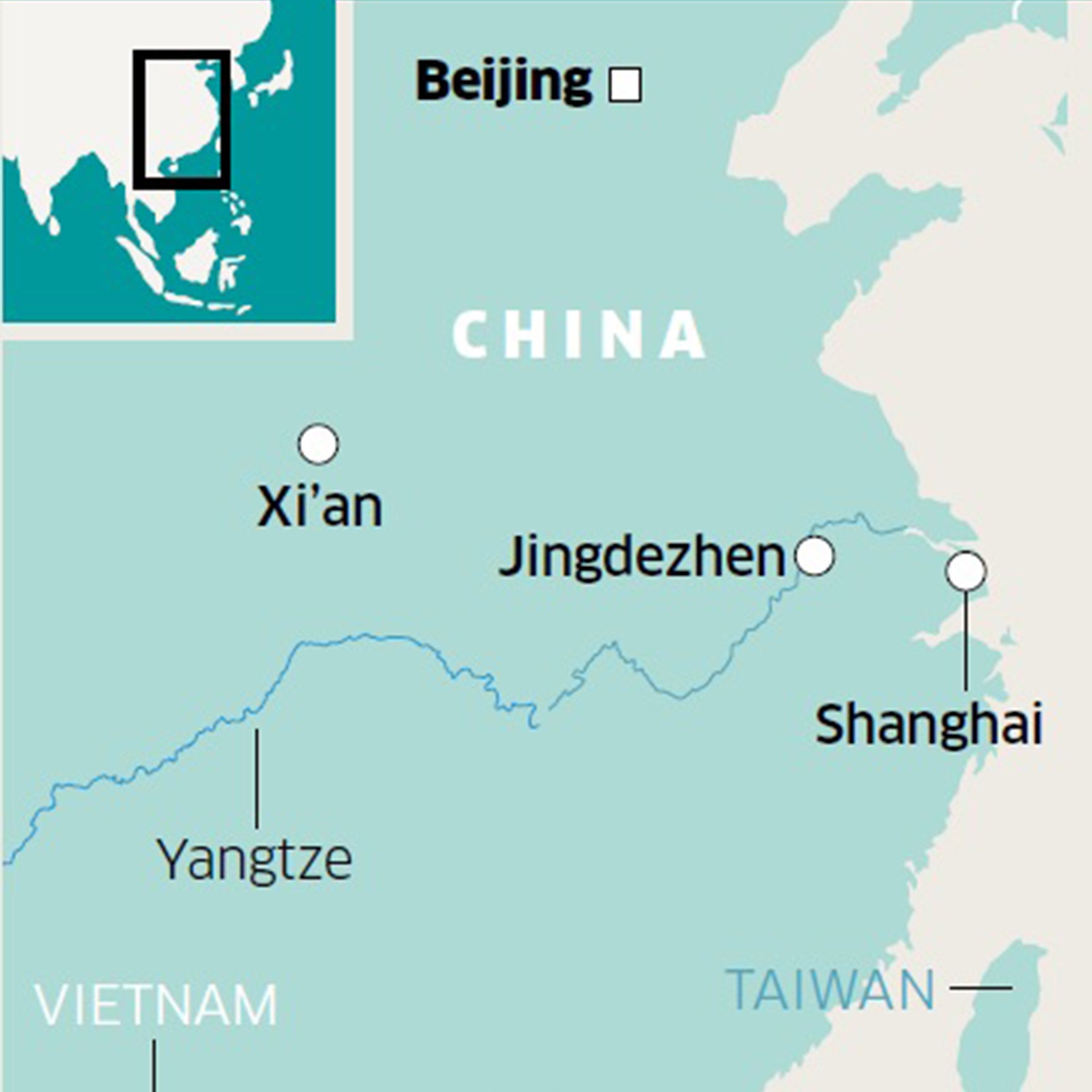

They couldn’t fathom how it was made, but they knew where it came from: the town of Changnan. Changnan porcelain was so in demand it is believed that early traders took to calling the whole country by this town’s name. Mangled by foreign tongues, Changnan transformed into China.

Two millennia after porcelain’s invention, the town, now called Jingdezhen, is still one of the world’s most important centres for pottery production. At first glance it’s a small, unremarkable place of concrete mid-rises, cigarette-filled corner shops and plastic-chair restaurants. But I soon spot a sinewy, little man carrying bags of clay on a bamboo pole across his shoulders. I follow him into a network of back alleys where dusty, garage-sized studios house dozens of artisans, all men and many are wearing blue Mao-era overalls.

They are happy for me to watch them at work. A trimmer carves patterns in the moist, ochre clay. Next door a painter glides his slender rabbit-hair brushes slowly across a vase, magicking into existence a fluid Chinese landscape. A few blocks down, a scrawny man dips some pots into a vat of glaze one last time before the kiln. Elsewhere, in a much larger workshop, two throwers work together in perfect unison to spin enormous jars, some taller than themselves.

“The people are the most important treasure here, their roots are deep in history,” says Jia Zhang, a student I meet later at the Pottery Workshop. She’s part of a new wave of designers who have come to Jingdezhen to learn techniques handed down and refined over a hundred generations. “This is the best place to study pottery in China, perhaps in the entire world,” Jia Zhang adds.

Chinese artists aren’t the only ones drawn here. Founded in 2005 by internationally exhibited ceramicist Caroline Cheng, the Pottery Workshop runs classes, residencies for visitors from around the world and tours. It is housed in the Sculpture Factory which, despite the name, is a rather pretty, two-storey building with whitewashed walls and traditional grey-tiled, pointy-eaved roofs.

In the Pottery Workshop’s second floor studio, neat rows of powdered dyes in Tupperware boxes line the walls and yet-to-be-fired artworks are stacked on wooden shelves. Here I meet Trudy Golley and Paul Leathers, a husband-wife duo from Canada, who often take up residencies here. “In the West, one ceramicist does everything but everyone is so specialised in Jingdezhen – a piece can pass through 70 different hands,” Trudy says.

Paul tells me that when he first visited Jingdezhen there were no street lamps and only dirt pavements. There were workshops but their goods were bought by traders and sold on elsewhere. These days, stylish cafés and bars pop up next to concept stores where contemporary ceramics are artfully displayed. At one such shop, I admire tiny, handleless teacups perched on a thick wooden branch like birds.

In the West, we’ve grown accustomed to gentrification pushing out artists and local residents, but here in Jingdezhen, it might help save the traditional artisans. For much of the 20th century, Jingdezhen’s inaccessibility preserved age-old traditions. On the way out to San Bao Ceramic Art Institute, on the city’s edge, I get an eyeful of this remote geography – the unmade roads, bamboo-clad rolling hills and the streams running red with kaolin clay.

Set up in 2000 by local ceramics artist Jackson Li, San Bao was Jingdezhen’s first artist residency. Inside the old-style wooden building, I find Wenying, Jackson’s bespectacled, cardigan-clad sister, busy looking after artists from England and Japan. Over a cup of green tea, she tells me how Jingdezhen has changed over recent decades. Factories have popped up on the city’s outskirts, which trade off the town’s 2,000-year-old reputation while undercutting genuine artisans with cheaper, poorer quality goods.

There may yet be hope. As the popularity of the Pottery Workshop’s Saturday craft fair and the concept stores attest, China’s hipper twenty- and thirty-somethings are more interested in unique, individually-made products. While they’re plumping for a contemporary look, many of the designers behind these ceramics are using Jingdezhen’s master craftsmen to make them because they know they offer quality, attention to detail and the small production runs that industrial factories can’t.

Perhaps Jingdezhen’s artisans will live on after all. Perhaps even, “Made in China” will again become the prestigious label it once was.

Travel Essentials

Getting there

The closest major air gateway is Shanghai, served from Heathrow by British Airways 0344 493 0787; ba.com), Virgin Atlantic (0344 209 7777; virgin-atlantic.co.uk) and China Eastern (020 7935 2676; flychinaeastern.com).

Shenzhen Air (00 86 755 88814023; global.shenzhenair.com) flies from Shanghai to Jingdezhen.

Alternatively, if you are travelling from Beijing, Air China (0800 86 100 999; airchina.co.uk) flies from the capital to Jingdezhen.

Visiting there

The Pottery Workshop (00 86 798 8440582; potteryworkshop.com.cn) hosts a Creative Market for local designers on Saturday, 8am-12pm. San Bao Ceramic Art Institute (00 86 798 849 7505; chinaclayart.com).

Staying there

Jingdezhen International Youth Hostel (00 86 798 8448886; yhachina.com) has ensuite double rooms from RMB128 (£14).

More information

China National Tourist Office

(cnto.org).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments