Is the government’s overhaul of airline flight paths really as green as it seems?

Analysis: ‘Take one for the planet,’ is the message – but adding capacity to the UK’s airspace could enable 400,000 more flights to fly to, from or over Britain each year

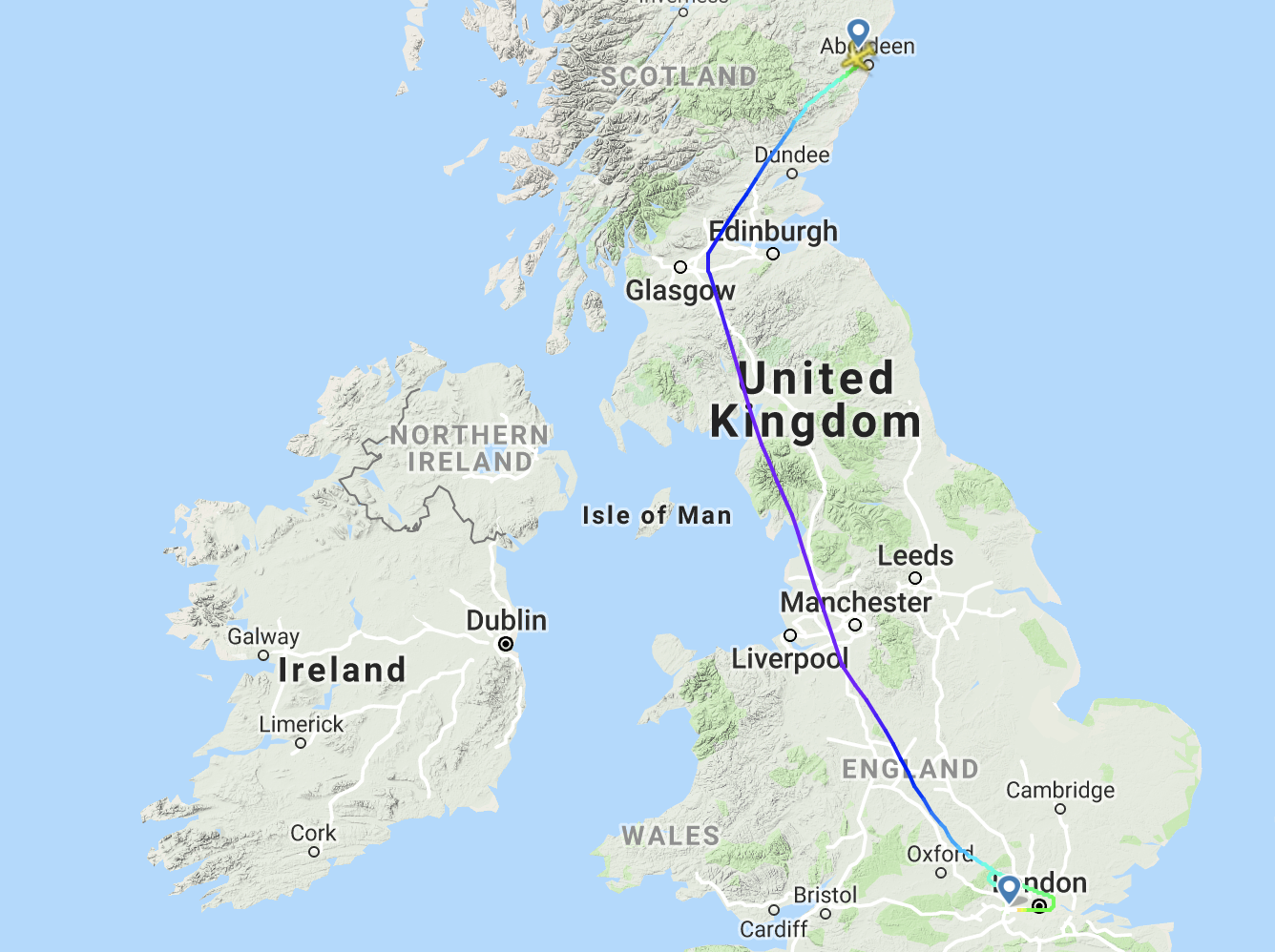

Had the last day of May dawned more clearly, the passengers aboard British Airways flight 1301 with window seats would have enjoyed a splendid tour of the UK as they flew from Aberdeen to Heathrow.

The direct route between Scotland’s third city and Europe’s busiest airport heads almost due south to Newcastle, then shadows the A1 trunk road to London. At 402 miles, a pilot flying an Airbus A320 by the straightest course could complete the journey in an hour.

But BA allows an extra 40 minutes in its published schedule. Partly the airline pads the schedule to allow for being ordered to "fly a holding pattern” before waiting to land at Heathrow, and partly because the journey actually flown typically zig-zags, adding 100 miles to the optimum path.

Playing back the flightpath shows that the BA Airbus flew southwest to Glasgow, then tracked down the west coast – clipping the Solway Firth and Morecambe Bay.

Well into the descent, passengers on the right may have glimpsed Oxford, before the plane meandered over the home counties and turned sharp right over City airport in the Docklands of East London for the final approach to Heathrow.

On the busiest day in history for Britain’s airspace, that flightpath devoured plenty of fuel – and an equally precious commodity, airspace.

The Department for Transport (DfT) judiciously chose 31 May, when for the first time more than 9,000 aircraft were expected to use UK airspace, to prepare the public for a radical reorganisation of the skies above Britain.

The way that airspace is carved up has not fundamentally changed since the mid-20th century. Navigation technology in the 1950s was primitive compared with today, and the best way to ensure safe separation was to confine planes to narrow corridors.

Since every 21st-century captain knows his or her location very precisely, the DfT – in collaboration with the air-traffic control provider, NATS – says it is time to set pilots free to fly the optimum course.

The government’s announcement has a strong emphasis on climate change: planes could burn one-fifth less fuel, “equivalent to 400,000 fewer flights a year”.

Yet besides cutting the environmental damage of each flight, liberating the skies will help airlines to cut costs

You might infer that pressure over climate change is finally having a major impact on policymaking in the transport sector. Yet in reality the DfT is craftily hijacking the green agenda to soften up the public for a project that will include adverse effects. Liberating airliners from those narrow corridors will diminish the noise nuisance for some, but means many more people will find they are beneath a flightpath.

“Take one for the planet,” is the message. But adding capacity to the UK’s airspace could enable 400,000 more flights to fly to, from or over Britain each year.

One aspect of the plan, though, will meet no opposition: an end to “stacking". In the perpetual game of three-dimensional chess played by air-traffic controllers in the most congested airspace in Europe, many planes fly in circles over the home counties while waiting to land at Heathrow.

Everyone can see it makes sense to keep an aircraft on the ground at the departure airport until it can fly direct to the destination. The problem has been that other planes can show up, for example from across the Atlantic, in a fairly uncontrolled fashion. But in an era when Uber can tell you that your ride will arrive in exactly 12 minutes, intelligent sequencing must surely eliminate the most wasteful aspect of flying.

Greener and faster: that is the government’s message.

Yet besides cutting the environmental damage of each flight, liberating the skies will help airlines to cut costs – and fares. Which will ultimately incentivise more of us to fly.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments