Try some vintage Greek island-hopping - jump aboard the first ferry out

Tash Shifrin goes on a voyage of discovery around the Greek Cyclades

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Everything looks different in the clear light of the Aegean sun. In the dark, my randomly chosen Greek island, Serifos, was just a lumpy black shape against the night sky, but the morning sunlight reveals a gem.

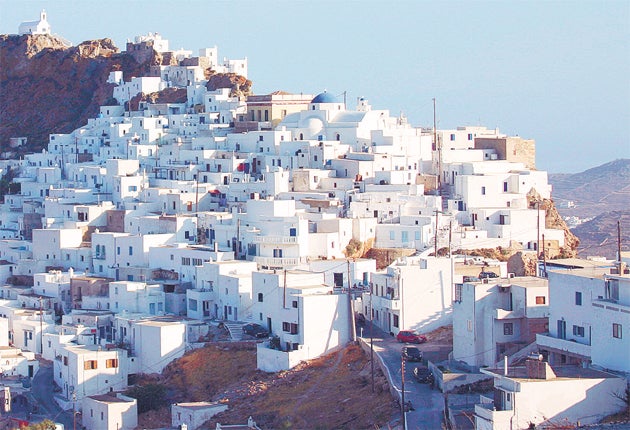

Beyond the small, dusty port of Livadi, with its wide, serene bay, is a triangular mountain. Stacked around the top are the classic sugar-cube houses of the Cyclades islands, right up to a church at the summit, gleaming white. From there, the view is glorious – and the hidden hilltop village is revealed, all classic white walls and blue woodwork. I can't believe I didn't set out to come here all along.

This was an unplanned destination. The harbour-side sign back at Piraeus, a hop on the metro from Athens, points straight out to sea. "Departures", it suggests. All possibilities lie open. I survey half a dozen afternoon options where the Cyclades boats depart, rejecting the familiar Mikonos and Santorini – too crowded, too loud – and the "fastboats" – too fast. Off the cuff, I choose a one-way ticket to Serifos on a friendly old ferry. It's three stops out, with an hour or 90 minutes between islands, so it's a before-bedtime destination.

And Serifos is a restful place. Along with its hilltop settlement, the chora, it has a series of beaches and is crossed by cobbled paths. But Serifos has another history. In Livadi, over a fine, grilled-fish supper, taverna owner Takis Alexakis explains the meaning of a plaque, dated 1916, on one of the chora buildings. Serifos in those days had an iron mine, where conditions were harsh and hours long for the 5,000 miners. There was a strike and a protest. Police opened fire, killing four workers. "Then the wives of the people who died, they killed some police," Takis says. "In the end they won an eight-hour day, the first in Europe," he says proudly.

At Mega Livadi, to the west, the old mine workings and rail tracks remain, along with a memorial. The Serifos mines shut down in 1964. But the miners catch up with me a few days later. I take a ferry to tiny Kimolos – named from the Greek for "chalk". Its rocky sides are stark white, pale lilac, butterfly yellow or streaked with a sharp rusty red. The miners still work here, digging out dazzling white bentonite.

The island's 500 residents don't care whether tourists come or not. Kimolos is happily self-sufficient. In the tight, winding streets of its chora, some paving stones have not only been edged in white but decorated with flowers, hearts, sailboats and slogans: "My Kimolos, my paradise". Visitors need to be self-sufficient, too. There is scant choice of rooms and a taverna may be open – or it may not. But it is small enough to walk all over, admiring the strange rock colours and lush vineyards. Apart from the stark white strand under the quarry road at Prassa, I find every beach deserted.

Bustling Milos, reached by a small, clanking ferry, is almost a shock. The tavernas in the busy port of Adhamas (or Adhamandas) are humming with conversation – mostly Greek or French.

Minerals, geology and strange geothermic activity have been the making of Milos. In ancient times, it was a source of the hard, black obsidian used for blades and arrowheads. On Paleochori beach, below red, purple and yellow-streaked cliffs, it feels as if the heat of the sun is somehow beating upwards from under my towel – in fact, it is geothermic heat and really is coming from underground.

The island's best-known product, also of stone, is the world-famous statue of Aphroditi – or Venus de Milo, as she was renamed when the French nabbed her for the Louvre. The olive grove where she was first unearthed is a short walk from Plaka, the ancient capital. There is a mournful plaque, and, in the local museum, a replica.

From Plaka's castle, the view takes in the whole of Milos spread out below and, receding into the distance, the islands behind and ahead. It is breathtaking. Poor Aphroditi, trapped in the Louvre – she must miss it here.

How to get there

Tash Shifrin flew to Athens with British Airways (0844 4930787; ba.com), which offers return flights from £142. For ferry information go to gtp.gr and danae.gr. Note, schedules can change at short notice and crossings become less frequent outside high season. Before you set off, check that you can get a boat back to Piraeus from your final destination in good time for your flight. Expect to pay €20 to €30 per night for a room with a shower, less if you stay for a few days. Beware, rooms are scarce in high season.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments