Portugal's Alentejo: A corker of a trip

Adrian Phillips heads south from Lisbon to explore the Alentejo, a region blessed with impressive oak trees and cultural curiosities

Herdade das Barradas da Serra lay in Portugal's Alentejo region, at the end of an hour's drive from Lisbon through a sun-sapped landscape of dry earth and olive trees. Ten villas with terracotta tiles provided accommodation for tourists like me, but the scattered trees were the real business of the estate. And what odd trees. A grey, baggy bark flopped in runkled folds over their branches, but at mid-trunk this gave way abruptly to a smooth surface of chocolate brown that reached from there to the ground. It was as though the trees had tugged up their jumpers to feel the breeze on their flesh; with bushy crowns and boughs like raised arms, they called to mind a troupe of crop-topped dancing girls.

These were cork oaks, their trunks stripped naked of the outer bark used to make cork. Harvesting bark is a specialist job performed by workers known as extractors. "It's part technique and part art," said Luis Dias earnestly, passing me a hand axe with the cross-palmed reverence of a priest conferring the communion wafer. An extractor makes a horizontal cut – or "necklace" – around the trunk at a height three times its circumference, followed by a straight cut down to the base. The bark is then prised away carefully with the flattened end of the axe handle, removed like a corset from a sturdy matron. The extractor must be strong but precise, for if his incisions are too deep or too high then the tree will die. He's a surgeon using a murderer's tool.

Luis took me to the top of his estate, bumping along a flinty track in a 4x4 until we reached the brow of the highest hill. From here, the land swept away into a rolling sea of treetops, falling and rising over hill ranges that lined up in choppy rows far into the distance. Luis owned everything up to the second row, he said, a total of 600 hectares of cork forest that had been in his family for 200 years. I sensed the weight of history at his back. "A fire could finish the business overnight," Luis nodded thoughtfully, as we watched a man clearing the ground of the scrub that is oh-so-flammable in the 40-degree oven of summer. If that happened, his eyes told me, he'd have failed where four generations before him had not.

But such pressures are far from the minds of tourists staying on the estate, who are drawn to its peace and shady prettiness. I followed one of three meandering trails through the oaks and eucalypts and umbrella pines, quiet routes where guests walk or ride horses, pausing on their way to watch the harvest in high summer. It takes a decade for stripped cork to re-grow, and each trunk on Luis's land is painted white with the year it was last harvested. From June to August, the extractors come to this mathematician's forest, travelling as a gang of 20 for hire to shear the ready trees of their booty, before the bark cuffs are collected by lorry to be boiled and pressed flat, and then punched through for bottle stoppers like sheets of Swiss cheese, or cut square into tiling for houses.

The capital of Alentejo is Evora. I drove there the next day along a road cushioned by thick verges flaring with poppies and purple thistles. It is said this region lies 50 years behind the rest of Portugal, hugging the bank while other parts drift free on swifter currents of time. I passed few cars on my journey. Old women in scarves and woollen hats sat watching nothing happen, the window frames of their whitewashed village houses painted blue to deter the mosquitoes or yellow to ward off the evil eye. Horses drank at a stream; brown cattle stared glumly between elegant horns; mechanical diggers truffled on a rubbish tip while above them 60 white storks trailed skinny legs in circles as they waited to feed on the flies. And then, Evora's 16th-century aqueduct hove into view, its arches leapfrogging the road and disappearing beyond the city's medieval walls.

My first stop in Evora had to be the cork shops, clustered on a street off the main square, to see the end game of Luis's labour. Shoes and shuttlecocks, place mats and pin boards, wine coolers, wallets and fishing floats – cork gets around. It's at the core of a cricket ball and the handle of a conductor's baton. In the old days, baseball cheats would hollow their bats and fill them with cork, believing it allowed them to hit the ball further. Alentejo's cork workers are similarly resourceful. Shelves were filled with cork cowboy boots, cork umbrellas, cork aprons and cork covers for iPads. There were cork cushions and cork business cards, even a wedding dress decorated with paper-thin cork lacework. When the Obamas visited in 2010, Barack was presented with a cork tie, Michelle with a cork purse, their dog with a cork collar.

But Evora wasn't awarded Unesco World Heritage Site status because of its cork shops, and so, armed with a cork key ring in a little bag made from cork, I joined Olga Miguel for a tour. Evora is a small city of square-cobbled lanes beneath eaves plugged with the muddy nests of swifts that wheel and cry overhead. Diana Square, the historical heart, gathers around the 14 Corinthian columns of a first-century Roman temple. In medieval times, the spaces between the columns were sealed with walls and the space inside used as a slaughterhouse. Olga said she suspected that the henchmen of the Portuguese Inquisition relied on the noise and gore of the slaughterhouse to mask their own bloody deeds in the cells of the palace next door.

We moved behind the main square to Evora Cathedral, a Gothic masterpiece of rose stone with hulking towers and toothy crenellations, and a gaping entrance surrounded by apostles on white pedestals. Against the dull air of the interior, an 18th-century altar popped and flashed with gold from Brazil, a flaunting reminder of Portugal's former colonial power. Nearby, in front of a gilded panel carved with creeping vines, stood the 15th-century statue of a pregnant Madonna, lips painted ruby red and with a hand laid on her bump. The statue survived only after being hidden from the forces of the Inquisition, who had ordered its destruction for making Mary seem too human.

Evora was once Portugal's second city, a place of wealth and influence, and – because Lisbon was destroyed by an earthquake in 1755 – it contains the country's richest medieval architecture still standing. We ducked into the Church of St Francis, the royal place of worship during the 15th and 16th centuries, and visited the remains of the palace opposite, decorated with sculpted stretches of ship's rope and Islamic-inspired filigree windows, a chiselled celebration of Portugal's maritime strength and the discovery of exotic lands by voyagers such as Vasco da Gama.

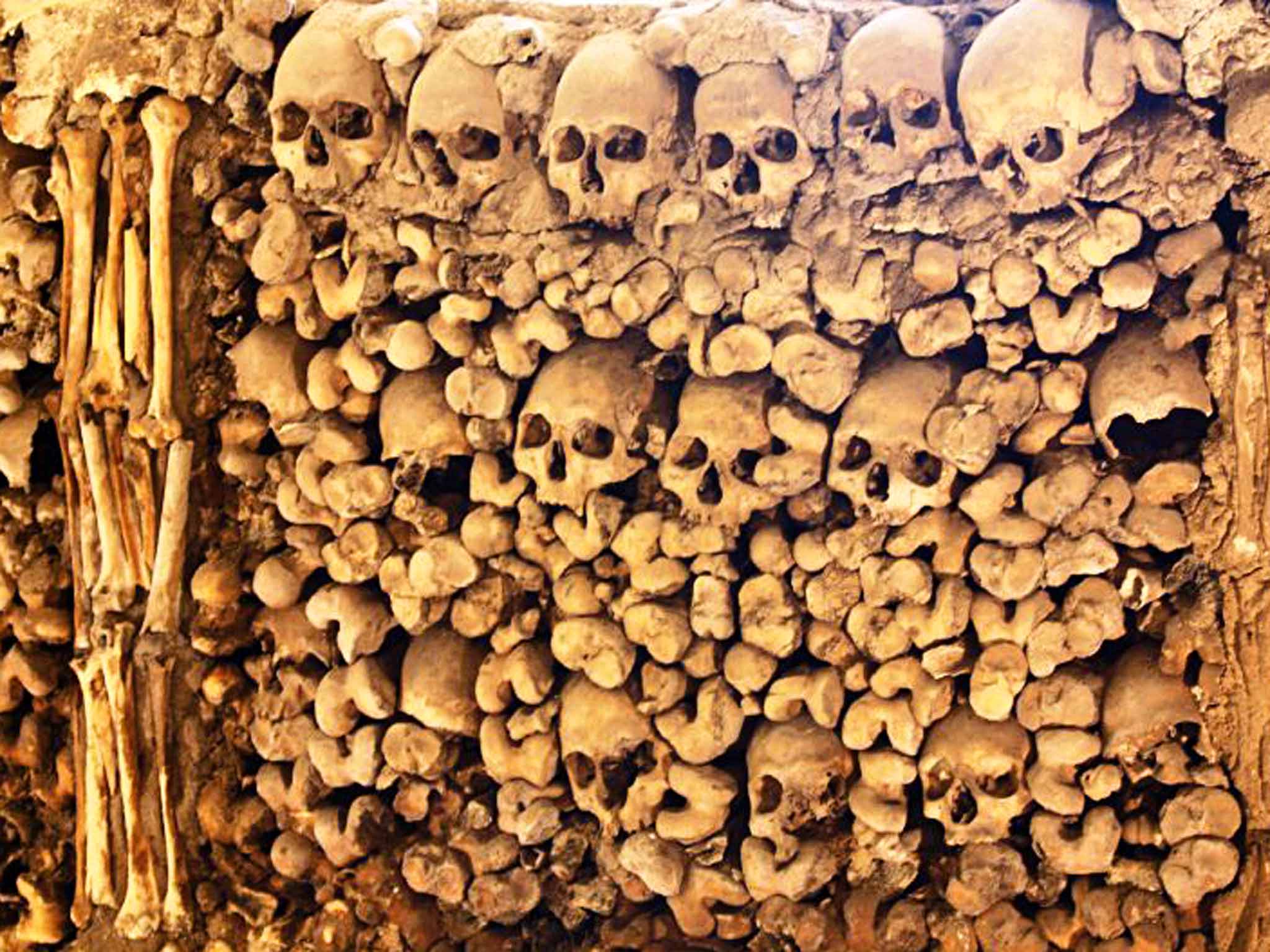

Finally, Olga beckoned me across monastery gardens into a chamber made from human skeletons. Yes, skeletons. Countless eye sockets ogled through the gloom, the walls packed tight with skulls and the notched ends of bones. Scores of tibias and femurs stood to attention as supportive props, while above them more skulls were cemented in rings around the column capitals. The centrepiece of the room was a mummified body, hanging limply from a beam like dried meat in a butcher's shop. A sign read "We, the bones, are lying here waiting for yours", and the ceiling bore a fresco of butterflies flitting towards inevitable death in the flickering flame of a candle. The Bones Chapel was built by Franciscan monks in the 15th century from the remains of 5,000 people, whose graves – originally dug outside the city – had to be moved as Evora spilled beyond its Roman walls.

The chapel was intended as a mammoth memento mori, a place to encourage the monks to contemplate life's transitory state. I bet it worked. I watched Olga prod tentatively at her own cheekbones as she peered close at a bleached head in the wall. I found myself wondering at the lives behind the bones. What did that person do, the one with the gappy teeth? Carpenter? Lawyer? And what about that man over there? He must have been a man – look at the width of that brow! Was he teased for his caveman features? No two skulls looked the same. Each bony brick was as individual as if it had hair and skin and blinking eyes; these body bits personalised death in a way that gravestones cannot. All except the mummy. That looked like a lump of cork.

From Evora I wended a gentle way north-east and climbed to the fortified village of Evora Monte, its castle looming above the surrounding fields, before levelling eastwards through the green-netted vineyards of wine country, around another hilltop castle at Estremoz and past the quarries of Vila Vicosa, their cranes shifting vast marble slabs like a herd of disciplined diplodocuses.

Finally, at sunset, the road zigzagged up to the impossibly quaint town of Monsaraz. From the lofty walls of its ruined fort, I watched pink light puddle on Lake Alqueva to the south. The lake has only existed since 2002, when the Alqueva Dam was constructed and the landscape flooded to provide a source of hydroelectric power. It was odd to think that those islands breaking its surface were recently the peaks of hills; as Portugal's economy sinks, some might see a metaphor in this beautiful, drowned spot. But not me. People are starting to notice this rustic region, to seek simpler pleasures beyond the neighbouring Algarve. Yes, Alentejo will stay afloat, as surely as a box full of cork keyrings.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Adrian Philips travelled as a guest of Sunvil Discovery (020 8758 4722; sunvil.co.uk), which offers a tailor-made six-night Alentejo package from £592pp. The trip features two nights at Herdade das Barradas de Serra in Grandola; two nights in the five-star Hotel Convento do Espinheiro, a restored 15th-century convent in Evora; and two nights in villa-style accommodation at the four-star Hotel da Moura in Monsaraz. Car hire and flights from Heathrow to Lisbon are also included.

Eating there

The Hotel Convento do Espinheiro and Hotel da Moura both have excellent restaurants, while the A Escola restaurant (00 351 256 612 816; restauranteaescola.com) near Grandola offers superb regional cuisine.

Visiting there

Olga Miguel (00 351 915 015 600) runs guided tours of Evora, Monsaraz and elsewhere.

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks