Luxury hotels: A grand nostalgia for old-world opulence

Wes Anderson's new film features a luxury hotel in an imagined country. But do these cathedrals of hospitality and service still exist?

Let's begin with a straightforward question. You go to see Wes Anderson's new film, The Grand Budapest Hotel. You love the movie, a gaudy, fantastical evocation of aristocratic japes set on the eve of the Second World War. And when you see a movie you love, you want to go to the place where the action is set. So: how do I get to The Grand Budapest Hotel?

Naturally, I asked the producers. They said: "The film was shot at a studio in Germany, but the lobby of the hotel in the film was an old department store." So that's not tremendously useful. More helpfully, they added: "They looked at grand hotels across Europe and wanted a combination of many rather than any one. So, the inspiration is the Grand Hotels of Europe".

The Grand Hotels of Europe. Settle back, draw the curtains, grab a bucket of popcorn and be prepared, as they say in the movies, to go on a journey. For this is a straightforward question with an epically meandering answer. On the way, we are going to have to confront a few less straightforward questions. Such as does Europe really have any truly grand hotels any more? If not, do you have to look somewhere else? And what does the term "grand" signify anyway?

Let's start our journey in Budapest. The hotel isn't there. It's just a name. Anderson sets the hotel in a fictional middle-European country called Zubrowka, which was, in fact, filmed in the German town of Görlitz, the location of an abandoned Art Nouveau department store that served as the Grand Budapest Hotel for the purposes of the film.

Still, are there grand hotels in Budapest that might just give you the GBH experience, Anderson-style? That style is cartoon-opulent. We are looking for acres of red velvet, hectares of marble, several tonnes of wrought-iron Art Deco signage, balconies, turrets, sweeping staircases and staff in ridiculous, military-style uniforms.

The author, Victor Sebestyen, the writer of Revolution 1989, was born in Budapest and specialises in the 20th-century history of middle Europe. He nominates The Gellert – "sort of".

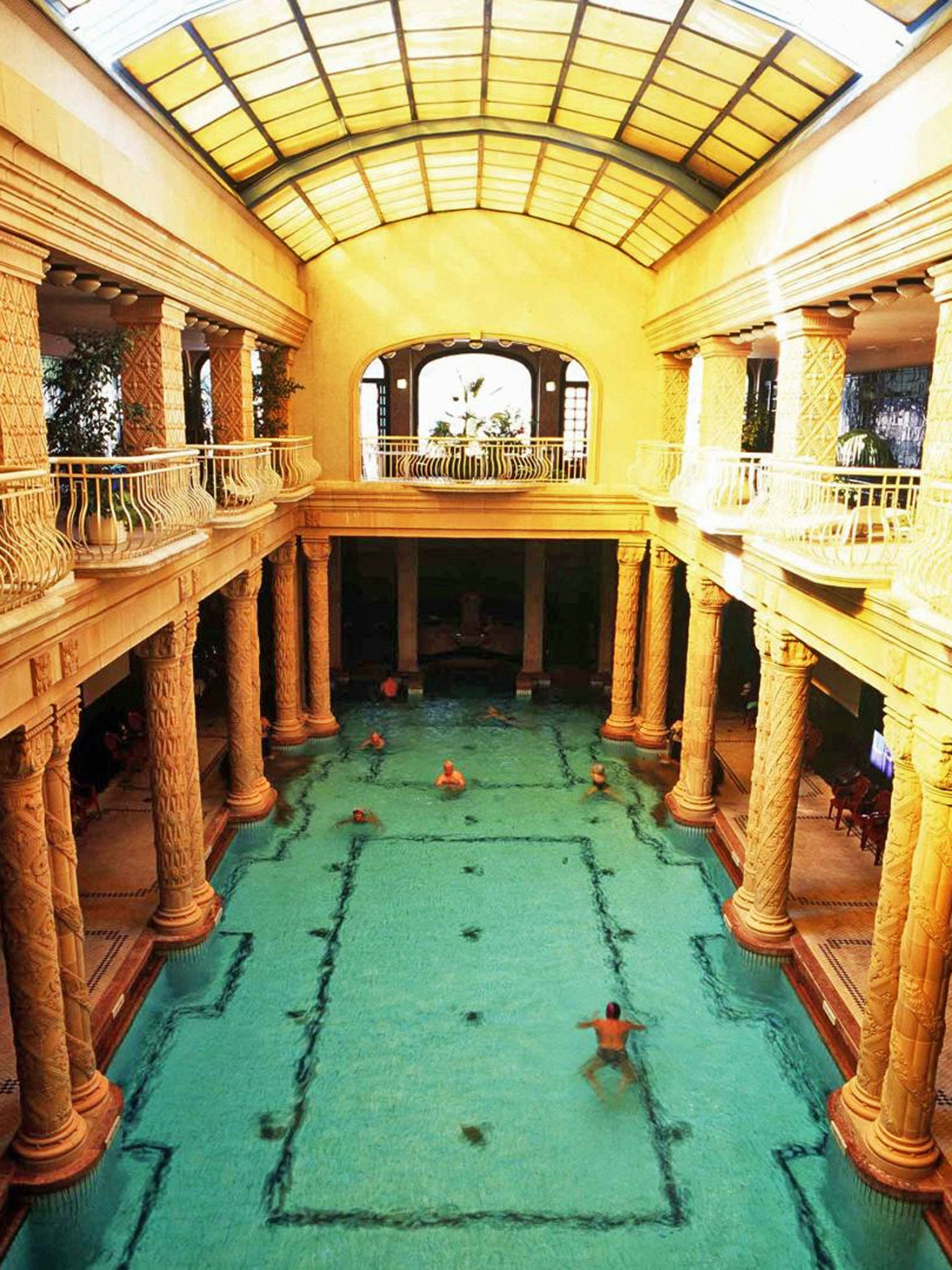

"It's so faded I'm not sure it counts any more," he adds with proper Mitteleuropa weariness. "Though its ornate Turkish baths and pools are fabulous".

They are. I've sat in them. And if we are to feel nostalgia, as Anderson does, for an era of opulence and misbehaviour the prosaic 21st century cannot possibly match, then perhaps faded is good. The Gellert certainly has the wrought-iron banisters, the domed ceilings and those amazing Byzantine baths. What's more, Wes Anderson himself name-checks The Gellert in his production notes.

Then again, it is a four-star: the rooms look like the Holiday Inn. We need to venture onwards.

The name "Zubrowka" sounds Polish to me. The only grand hotel I've stayed at in that country is the Grand Hotel Lodz. It's certainly imposing and has one of those Art Deco entrances that you see in the film. Yet it's hard for me to recommend the place to the amateur location scouts among you. In its restaurant, I had the single most depressing meal of my life. The starter consisted of a limp lettuce leaf (yes, just one) bathed in condensed milk. There were no wines on the wine list, just Russian cola. The only excitement was the presence at the bar of Jan Tomaszewski, the Polish goalkeeper who defied England and denied Sir Alf Ramsey a place in the 1974 World Cup Finals. True, this was still the Communist era. But if the website is anything to go by, the rooms haven't changed much.

Sebestyen himself has spent many man-hours cradling strong coffees and stronger spirits in various central European grand hotels while researching his books. I wondered if the statesmen, tycoons, blue bloods and spies had all moved to The Four Seasons and Hyatts?

But no, he says: "They still matter, the grand hotels, as the places to be seen, and where business is done." But, in his view, there are only three left in central/eastern Europe which are models for the grand-hotel style.

There's The Adlon in Berlin, financed by Kaiser Wilhelm II, opened in 1907 and a hotel that has seen more 20th-century European history than anywhere. But the current hotel is not the original: it was rebuilt by the Kempinski group 90 years after the original opened.

Then there's The Astoria in St Petersburg, which is now owned by Rocco Forte, and has been restored to its Tsarist glory and ranks highly on the plush red furniture scorecard.

Sebestyen's final choice, The Imperial in Vienna, is unquestionably the grandest of the grand hotels on the list – a palace where emperors, kings and queens feel at home.

I'm not going to point you towards London or Paris. The nearest thing we have is The Café Royal: it retains the memories of naughty deeds committed on red-velvet banquettes under twinkling chandeliers. But it is not a dominant building; and it has just been done up. I don't think we want too much contemporary refurbishment in our fantasy grand hotel. The Dorchester? Too flat-fronted. The Savoy? Too discreet. The Ritz? Too human-ised. The Lanesborough and Corinthia have the scale but neither the location nor the history. Even the Parisian palace hotels are not quite on the right scale. Perhaps The Crillon and The Ritz come closest – but they, again, have got the decorators in.

And as we get further from the era portrayed in Anderson's film, so tastes move yet further from the masculine, bombastic styles of the classic Grand. When the Georges V in Paris opened, it did so with lilies, limestone and light. Today's hotel designers are furiously feminising: like the Plaza Athénée, they want to be a location for Sex in the City, not The Tales of Hoffmann.

So, I went back to the movie poster and realised I was looking in the wrong place. We need to get away from the cities. The poster features the model of the imaginary Grand Budapest Hotel that was created for the film. You see a huge, pink castellated thing set against an Alpine – or is it Caucasian, Carpathian or Swabian? – backdrop of Gothic peaks and terrifying outcrops. The building itself doesn't look as if it belongs there. (Damn those indy creative director types).

If you want pink and castellated, I suggest you head to the Loews Don CeSar Hotel at St Pete Beach on Florida's Gulf Coast. It has all the pink turrets you'd want, and probably more. But it also has dunes and palm trees, not pines and craggy cliffs.

Brenners Hotel in Baden-Baden is closer to the mark. It is exquisite, classical and certainly pinkish in certain lights. Statesmen, spies and femmes fatales have all schemed in its shady paths and marbled rooms. And it is close to the Black Forest, where there are plenty of pines and rocks. Yet Baden-Baden itself is too sunny, too hedonistic for our purposes. Brenners wouldn't be at all right as a backdrop for The Good Soldier Svejk, the strange 1920s Czech novel that apparently inspired Wes Anderson. (But, as a backdrop for the British novel of Edwardian resort hanky-panky, The Good Soldier, by Ford Maddox Ford, Baden-Baden can't be beaten).

We need to go higher. At Pontresina in the Swiss Alps there is a marvellous hotel called The Grand Hotel Kronenhof. It is rather smaller than the Grand Budapest Hotel, but the designs are strikingly similar. Inside, it is traditional, impeccable and utterly delightful – and thus maybe not sinister enough for our purposes. And Pontresina itself, though the setting is sublime, is perhaps a little too sensible and Swiss.

For epic, Byronic grandeur you probably have to go up the road to its sister hotel, The Kulm Hotel St Moritz. The design is the stockbroker/Swiss banker version of classical, however. Badrutt's Palace Hotel, a little way down the valley, is more like it: a properly scary and gigantic congregation of balconies and spires and turrets.

Wes Anderson said it was the otherness of the European experience that made him want to make the movie. And, certainly, you don't find many models for the Grand Budapest Hotel in his hometown of Houston, Texas. But, in the end, I wondered if his location scouts didn't have a sly peek around their own backyard?

There is one particular hotel I am thinking of. Part palace, part cathedral, part ministry in style, it sits on a cape and completely dominates the town. There is a river far below and, in winter, the whole area is covered in snow and ice. It's gigantic: 611 rooms and suites. That town is Québec and the hotel is Le Château Frontenac, operated by the Fairmont Group.

And guess what? Most of it is closed for renovation. Looking at the designer's visuals, the reborn hotel is going to be sexy, feminine and not at all the kind of place Gustave H, the lecherous concierge played by Ralph Fiennes in the movie, would thrive in or approve of.

Here's the not-very dramatic dénouement of our story. There are plenty of hotels which bear the name "grand". Yet, in an era where you can wear jeans and trainers in any hotel restaurant in the world, where the scent is not of leather and cigars but of lavender aromatherapy candles, where the concierge has a PhD and the porters wear Armani – quite simply, nowhere is really grand any longer.

Stars check in: Which hotels inspired the film's director and actors?

Wes Anderson (director)

On the country of Zubrowka: "Our country is invented. I think it combines Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland – it mixes together many countries."

On the hotels that inspired him: "Travelling around eastern Europe, going to places like the Gellert in Budapest and the Carlo IV in Prague … there is a layer of history in the architecture. Communism is very present when you visit these places. You see the old place, and the newer place inside it, and then the newer period inside of that."

Edward Norton

"There's a hotel in the northern Czech Republic called The Grand Hotel Pupp, P-U-P-P. It's in Karlovy Vary, which was the German spa town called Carlsbad. It's evocative."

Willem Dafoe

"Jeff [Goldblum] and I were around for a lot of the shoot and we'd see characters come and go. It was like guests checking in and out of the hotel. So, we were kind of like residents of the hotel. There was a whole parallel adventure of life to the fiction of the movie."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks