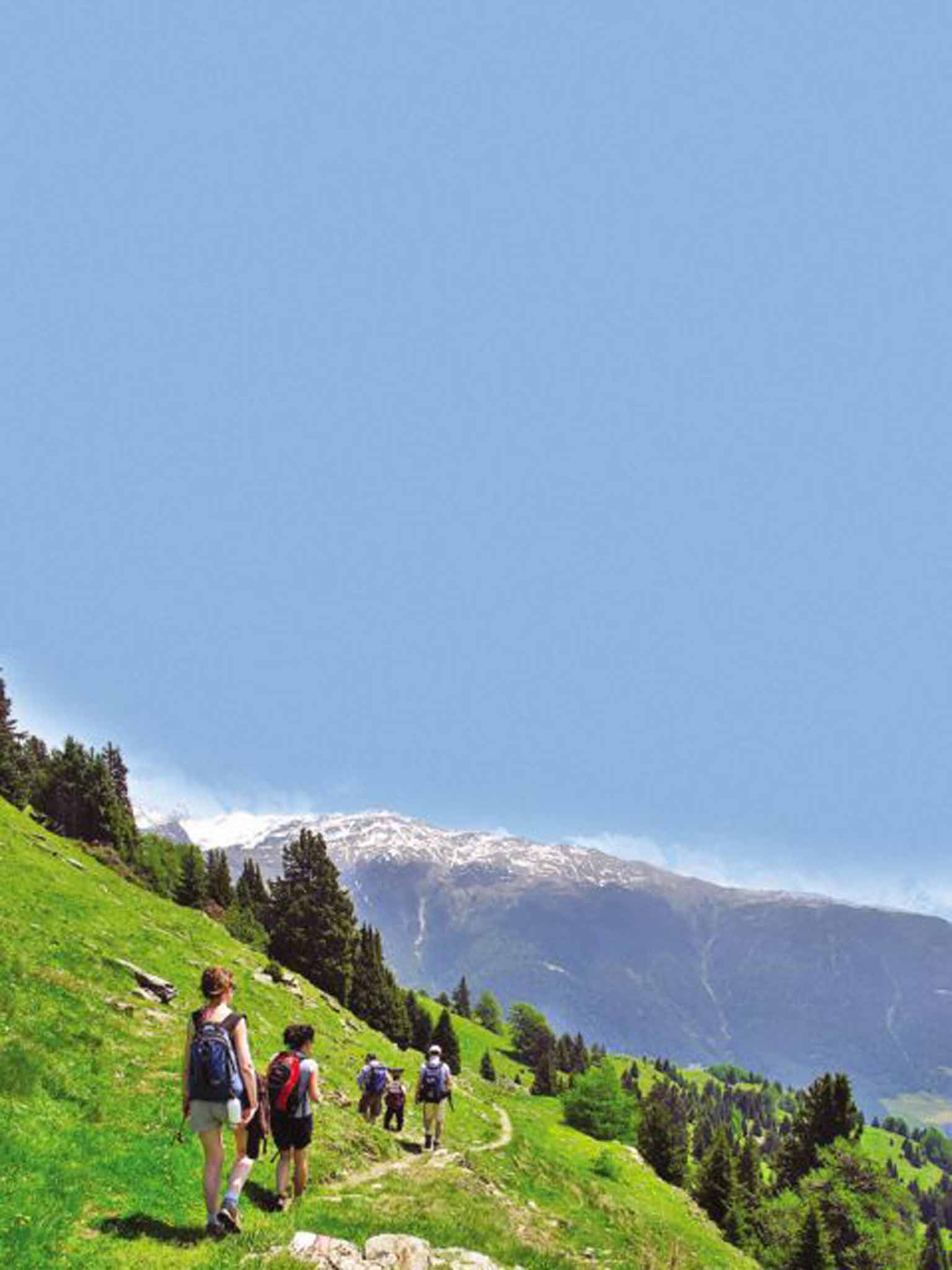

Hiking through Italy's South Tyrol: Healing treatments, Alpine blooms, and a First World War battleground

The picturesque Vinschger route through leads walkers from Reschen on the Austrian border to the beautiful spa town of Merano

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As I unpacked my bag, a profusion of pressed wildflowers tumbled out of my notebook. I had given up trying to record their names – from the globe-like, bright yellow "troll flowers" to the deep blue gentians and the pretty pink alpenrose – and simply stuck them there for future reference.

I had picked them up along the Venosta trail, a 108km route through South Tyrol – the German-speaking part of Italy. Known as the Vinschger route in German, it begins at Reschen, a three-hour drive from Verona, on the Austrian border, and it ends in the beautiful spa town of Merano.

The path starts easily enough, curving around the edge of two lakes before climbing into the mountains. I was travelling with a cohort of four other 40-somethings during an early-summer heatwave, and my head was spinning in the 30C heat. So, it was a relief finally to plunge into the cool shade of the forest and be hit by the scent of pine needles.

Above us, the larch, spruce and pine trees were covered in lichen – a sign of unpolluted air, our guide, Christian, explained. Our feet found their way over the mosaic of roots, which looked like veins and appeared equally alive, as they vibrated with ants engaged in mortal combat over twigs. We stopped to freshen up at a small waterfall cascading from a spring, before climbing further still, all the time followed by the insistent warning of a cuckoo.

I couldn't quite believe it when I saw a large patch of snow on the ground and had to touch it to check it was real. But then we turned a corner to see a far more impressive sight – the snowcapped peaks surrounding the Ortler, which until the First World War was the highest peak in the Habsburg empire, at 3,905m.

One hundred years ago this month, Italy launched a disastrous offensive against the Austro-Hungarians, which would cost a million, mostly Italian, lives, in one of the most protracted conflicts of the war. Indeed, several times when the Italians were going over the top, the Austrians shouted at them, begging them to go back, to spare mowing them down with machine-gun fire.

In the glaciers opposite us, soldiers lived for months in tunnels under the ice. Stuck in stalemate, the two sides were reduced to firing shells above each others' impenetrable positions to set off avalanches behind them.

After the war, Italy seized the region, but Benito Mussolini was so fearful of his Germanic allies reclaiming it by trooping down the Venosta valley, as we were doing, that he built a series of defensive bunkers, which you can still see at Reschen and Tartsch.

We arrived at the pristine village of Planeil, our luggage awaiting us at the tiny Gasthof Gemse, where we would spend the night. Planeil's farmsteads cling on to the mountainside, and much of the food at the Gemsehof is grown in its own steep garden – such as the asparagus in our risotto, which came topped with multi-coloured petals.

Equipped with a packed lunch prepared by the hotel, we tackled the 2,324m Spitziger. On the way to the peak, Christian pointed out the juniper bush used to smoke the ham in our sandwiches – which tasted delicious as we looked over the vineyards and orchards from this spectacular vantage point.

We stomped back down amid a peal of cowbells, feeling as if we were in the middle of a glockenspiel, until we waded into ungrazed meadows, with an abundance of wildflowers splattered across them like paint. Of course, among the Alpine blooms were – for unwary shorts-wearers such as myself – merciless stinging nettles. So, after 17 kilometres, I was grateful to arrive at the Almhotel Glieshof.

We each had our own ways of dealing with the exhaustion. One of our party went on a run towards the glacier where Ötzi, a 5,300-year-old iceman, was found. Others downed several steins of beer served by waitresses in a dirndl dress. I went to the spa. South Tyrol is famous for its healing treatments – this is where the "hay bath" was invented. Even a remote hotel such as the Glieshof has magnificent Byzantine-like steam rooms and saunas. As in all German-speaking areas, they are mixed and nudist.

The wine helped, too. Each night we would choose a bottle from a village we had passed through – fresh, aromatic, zingy whites and light, fruity reds – which we would drink on the terrace while listening to a group of hunters play music on their horns.

Although I considered myself one of the fitter members of the group, my knees had not reckoned on the jarring impact of the descents on an often uneven path. Nor had I thought to bring walking poles. On the third day, it got to the stage where Christian had to give me a piggy-back until we were back on the flat.

Fortunately, this was our last day of walking, halfway through the trail, and a well-deserved three-day spa break awaited in Merano – a Habsburg gem of a town, ringed by mountains, at the end of the trip.

Here, I explored the buzzing cobbled streets between Baroque houses and stunning restaurants, before recuperating in the 25 pools of the palm-lined Riviera-style spa. A finale that was as delightful and unexpected as the wild flowers in my notebook.

Getting there

Colin Nicholson travelled with Inghams (01483 791 114; inghams.co.uk), which offers four-night holidays to the Merano region with half board at the five-star Mignon Park hotel, as well as return flights to Verona and resort transfers, from £888pp.

Visiting there

The Venosta trail is marked (bit.ly/Venosta) and a train (mobilcard.info) runs the length of the valley.

Meran Therme (thermemeran.it). Entry from €12.50 (£9.20).

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments