Charleroi: The city with art at its heart

Cathy Packe explores the urban canvases, both old and new, of charming Charleroi, Belgium’s very own ‘mini-Berlin’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

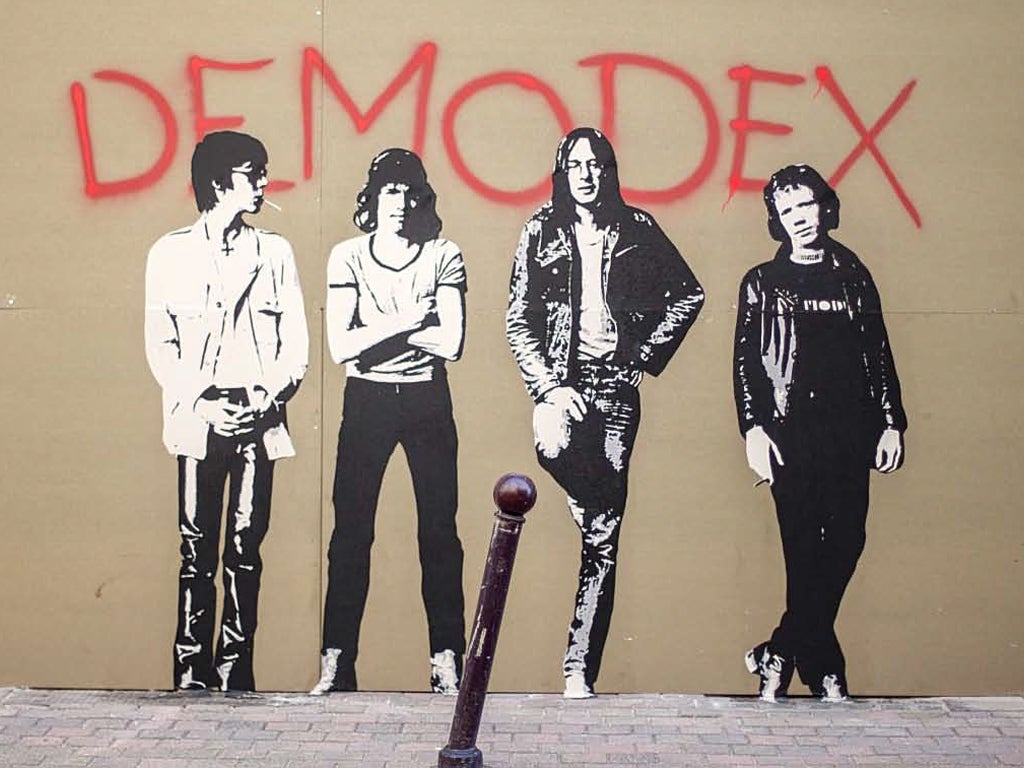

Your support makes all the difference.You find graffiti everywhere in Charleroi. On concrete walls, on the pillars that hold up the city’s elevated ring road, on the sides of apartment buildings. There are abstract shapes in bold colours, scenes of local history depicting coal miners and other industrial workers, and more recognisable figures, including local and global celebrities. Barely a dreary surface survives in this surprising city: every slab of concrete or brick seems to have been given colour and brought to life with strikingly professional modern design.

Here, graffiti constitutes not vandalism, but art. Not that the people of Charleroi are new to a bit of urban art. Two of their Metro stations are adorned with images of the cartoon characters for which the city is celebrated. Though Tintin belongs to Brussels, a gallery of his cartoon compatriots adorns the walls inside Janson station, while at the next stop, Parc, Lucky Luke is the main character in a cartoon adventure, drawn out on 21 panels along the far wall of the southbound platform.

For a city of barely 200,000 to have a Metro is itself remarkable, but Charleroi has appeal way beyond its scale. It has been described as a mini- Berlin, a place that is edgy, exciting and with a lot happening outside the mainstream. It has a biennial festival of urban arts, whose most recent events have left a permanent mark on the city’s exhibition centre. Its façade has been emblazoned with the words “Bisous M’Chou” – an affectionate acknowledgement by the artist Steve Powers of a local term of friendship and greeting. His aim was to create something that the community would identify with and embrace as their own.

While perhaps shocking to some, graffiti is little more than a bolder version of sgraffito – a technique dating back many centuries, in which a design is scratched into the surface of a building’s façade. It was frequently used in Art Nouveau architecture, an earlier artistic style that flourished in Charleroi.

Once among the most affluent cities in Europe because of its industrial riches – coal, steel, wood and glass – Charleroi, like Brussels, has an impressive collection of Art Nouveau houses in what were once the suburbs inhabited by the affluent merchant classes. The biggest concentration is in Rue Léon Bernus. Monsieur Bernus made his money from the monopoly he held on glass for windows. The Physician’s House, at number 40, has many typical features of the style: wrought ironwork, decorative windows with carved bas-reliefs above them on several floors. But as an example of 19th-century sgraffito, the red-brick Maison Dorée on Rue Tumelaire is hard to improve on.

No doubt when these houses were first built, the curious came to admire, and perhaps even photograph, the stylish new buildings – just as photographers come now to snap the modern graffiti and record the way the city is changing. And documenting change is one of the goals of Charleroi’s renowned Museum of Photography. Since 2010, the museum has commissioned a photographer to explore the local region and interpret it in their own way, at the same time creating a photographic memory of what they have seen. This process has now been incorporated into the framework of the activities that will form part of Mons 2015 in celebration of the choice of this neighbouring Walloon city as European Capital of Culture.

The Photography Museum itself was the initiative of an enthusiast called Georges Vercheval in 1978. He persuaded the city to support him, raised the funds to buy a collection of old cameras, and started collecting pictures. The museum opened officially some nine years later, housed in an old Carmelite convent on the southern outskirts of the city. Built in the 19th century in Gothic style, the rooms around its central cloisters are now the home to a regularly changing series of exhibitions; there are always three temporary shows on display. The building has been transformed into a modern exhibition space by the addition of an extension six years ago, which enables the building to house a permanent collection of some 80,000 photos, making it the largest, and one of the most important, museums of its kind.

The permanent galleries are organised in chronological order, and comprise a fascinating chronicle of society, events and the state of the world. The images are varied and often unexpected – as, sometimes, are the photographers. A number were taken by René Magritte, who was born in the area and spent part of his childhood in Charleroi before moving to Paris, and then Brussels, and finding fame in another artistic medium. Intriguingly, a photograph of Magritte himself, taken from behind, shows a man in a long coat and bowler hat, an image frequently found in his paintings.

The earliest photos in the collection, dating from the 1840s, are intriguing for the static nature of the images they portray: posed portraits, scenery which to modern eyes seems flat and lifeless. But as later photos show, the camera can bring a subject to life and give the viewer something to relate to – in much the same way as the best graffiti.

Travel Essentials

Visiting there

Museum of Photography, Avenue Paul Pastur 11 (00 32 71 43 58 10; museephoto.be).

Janson Metro station, corner of Boulevard Paul Janson and Avenue Général Michel.

Parc Metro station, corner of Rue du Parc and Rue Willy Ernst.

Eating there

Luxembourg brasserie, Rue du Pont Neuf 41 (00 32 71 31 63 59).

More information whybelgium.co.uk; 020 7531 0390

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments