Cruising from Aswan to Luxor: A lost jewel on the Nile

Memphis Barker lives like a pharoah with a whole riverboat and the nation's archaeological treasures all to himself

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Shortly before dessert, on my third day aboard The Oberoi Zahra luxury Nile cruiser, I was passed a mobile phone to have a word with the customer manager of Sakkara Tours, who had organised the trip. "Memphis," the voice said cheerfully, as I sat by myself in the dining room, "am I speaking to the pharaoh of the boat?" He was, in a way. I owe my name to an ancient Egyptian city and at that moment my kingdom occupied the whole of the ship, from the pool to the cigar room – including a population of 45 staff, though not a single other guest.

A touch of the loneliness Ramesses might have felt washed over me. For days the only people I had spoken to were being paid to attend to my every wish. Pleasant company, but liable to throw themselves at anything I might happen to drop – such as a teaspoon – as if it were a live grenade.

All other 26 cabins on board were empty. The scheduled cocktail parties had been cancelled. There was no hubbub in the dining room. I gave the phone back and looked for a moment at a freshly delivered crème brulée.

Depending on your social inclination and/or political views, there hasn't been a better time to visit Egypt. The flow of tourists has turned to a drizzle since the revolution in 2011. Advertisements in the UK show tanned couples on Red Sea beaches, as they always have, but newspaper reports have offered a different impression; protests, and then, in the summer of 2013, a massacre. The military coup which brought Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to power left behind a trail of dead Muslim Brotherhood supporters.

Once, Swedish CEOs rubbed shoulders with Saudi princesses on board the Zahra. Now there was only me, who may or may not have fulfilled the "elegant" dress-code required for dinner.

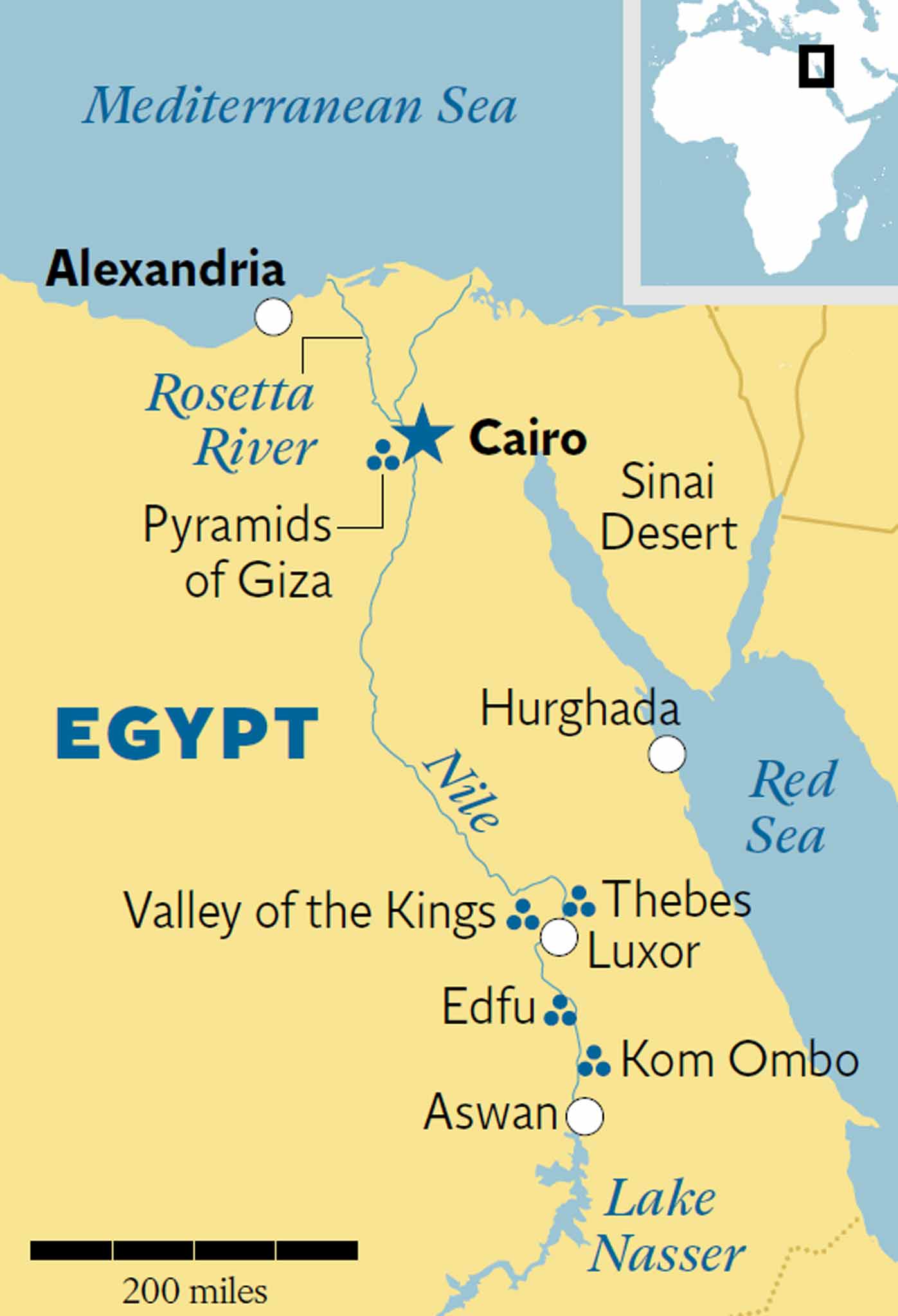

What splendour it was though, not least in my dark wood and marble presidential suite. The journey ran smoothly, with the four-deck cruiser moving at a pace which felt like something between a trundle and a jog. The city of Aswan – once a colonial hub for the English – bustles towards the port, from where we departed. Up the river, north to Luxor, the towns give way to great stretches of farmland on either side.

Each morning, I would drag back the suite's curtains, which covered the ceiling-to-floor windows, with priest-like care. The view had something reverential about it. The wide river. Trees on the banks, like the scrub on an upturned toothbrush. Small birds. The odd felucca.

After breakfast, Wael, the ship's tour guide, would lead the way to one or other of the temples that sit, squat and daunting, close to the river's edge. Kom Ombo (circa 2,400 years old); Edfu (c. 2,250); Karnak (c. 5,000). Each cuts through the complacency of a casual tourist, the glaze brought on by knowing one ought to appreciate something. To walk through the pylon façade of an Egyptian temple is to be spoken to not only by the size and grandeur of the architecture but, more remarkably perhaps, in a literal sense. Hieroglyphics cover the walls – directions on how and when to sacrifice what, offerings from rulers (Ptolemy, Seti, Thutmose) to gods (Horace, Thoth, Min).

The columns and the slabs and the altar-rooms all throb with meaning, a philosophy no longer fully decipherable. Occasionally Wael would stop and read, turning a duck, a beetle, a cane into vowels. So clear is the iconography – often so well preserved – that the effect is a pleasurable shifting of the sands. You can go in thinking there is no god and that the sun is a ball of flame, and find yourself, deep in the dark, open to the idea that the goddess Nuht's belly stretches out to form the sky and that all evil can be traced back to a god, Sobek, with a crocodile head.

Luxor, the home of Karnak, was the ancient city of Thebes. It brought agriculture and civilisation to Egypt at a time when the inhabitants of modern England were still working on piles of stones in Wiltshire. "Royal Thebes, Egyptian treasure house of countless wealth, who boasts her hundred gates/ Through each of which, with horse and car, two hundred warriors march," wrote Homer in The Iliad.

Across the Nile is the Valley of the Kings. The tombs of the pharaohs lie down sloping tunnels, cut into the mountains of Luxor. Inside, colours; four-millennia-old paint of a ferocity – a verve – that makes one feel that a century can pass in the click of a finger.

Twelve baboons adorn a wall in Tutankhamun's final resting place. Each represents an hour and offers the soul of the young ruler a piece of advice on how to reach the next one, so that he can make it into the afterlife through the first, crucial night after death. I would not now be utterly surprised if I see a baboon when my time comes.

Everywhere we went, at least when I pressed Wael on the topic, he would lament the lack of tourists. As we walked to the edge of the upper dam in Aswan, he gestured to a tiny cluster of American tourists and said, close to anger: "Before, you wouldn't even be able to stand here – there would be too many buses!"

Now he works a sliver of what he did before. Like many Egyptians, any revolutionary spirit he might once have possessed has dimmed. "After four years and no jobs," he said, "you are tired of politics." Sisi – a former general – offers security, at least. At the souvenir shops of Cairo airport, T-shirts emblazoned with the date of the uprising against Mubarak – 25 January – are now hidden behind racks of others and sold at a steep discount. It's thought that the ministry of antiquities, which is responsible for the upkeep of Egypt's incomparable ancient treasures, has suffered a 95 per cent decline in revenue since the 2011 coup. The cruise ships used to line up by the berths in row after row after row. Now, whenever we stop, there is never more than a handful.

For many, a fear of uncertainty and travel warnings keep them away from Egypt. For others, it's a question of ethics. Journalists may refuse to visit Egypt while three Al Jazeera staff remain locked up for reporting the news, and the LGBT community may be put off by President Sisi's arrest of homosexuals. But experience suggests a few more years of relative quiet will bring back the majority of British tourists. Already, some travel agencies report a pick-up in sales. To hear the stories of local hardship – "tumbleweed" said one hotel porter, when I asked how business was going – is to think that not so bad a thing.

The Oberoi Zahra offers luxury without snootiness. My towels were shaped into ever more elaborate animals by the housekeeping staff: a crocodile first; finally, a monkey hanging from the ceiling. The cruiser will run, I was told defiantly, at the same peak level of service no matter how many guests are on board.

The same choice on the menu, the same glorious chandelier lighting. It currently glides up and down the Nile – undoubtedly at a significant loss – almost as a figurehead for the Oberoi group's values. From Luxor, the final stop, the journey to Hurghada – and a busier Oberoi resort on the Red Sea – takes four hours and winds through the Sinai desert.

Hurghada is in better shape than most Egyptian tourist resorts, because it is a proper, small city that happens to have some appealing hotels and, north and south along the coast, great beaches. It is "mainland" Egypt, rather than the Sinai peninsula, which makes it a good adjunct to a cruise on the Nile. What it lacks in awesome archaeology it makes up for in good nature: wander around the market, plant yourself in a café and the world will befriend you. The Oberoi Sahl Hasheesh is international, friendly and profoundly comfortable. A place to connect with one's inner pharaoh, perhaps.

Staying there

The Ultimate Travel Company (020 3051 8098; theultimatetravelcompany.co.uk) offers a tailor-made nine-day stay in Egypt, including a four-night full-board Nile cruise aboard The Oberoi Zahra luxury Nile cruiser, three nights at The Oberoi Sahl Hasheesh, Red Sea (oberoihotels.com), and one night in Aswan at the Old Cataract Hotel from £2,398pp.

The cruise includes guided sightseeing and the overall price includes Egyptair flights from Heathrow to Luxor and private transfers.

Hurghada is served by Monarch from Gatwick, Birmingham and Manchester, and from Gatwick by easyJet.

More information

egypt.travel; 020 7493 5283

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments