Samoa: A paradise you really have to want to visit

This cluster of idyllic Polynesian islands may have hopped over the Date Line to join Australia in the future, but its traditions hold fast, says Nick Redmayne

At the Upolu to Savai'i ferry terminal an older man reclines on a bench below a café serving hatch, the Samoan equivalent of a greasy spoon. He catches my eye, raises half a coconut, smiles and beckons to me. I'm in no hurry, Samoa isn't a place to be in haste, and I wander over to see what he wants. My new friend dips a coconut shell into a blue plastic bowl filled with liquor of peeled potatoes or perhaps muddy socks. He passes the coconut to me. “Ava,” he says, raising his eyebrows. I drink the mud, which is bitter and gritty, and return the empty shell. He does the same, grins and gives the shell to an obviously thirsty friend. Then, all too soon it's my turn again. By now my lips and tongue are numb and my head is tumbling with the sensation that accompanies a first cigarette after failing to give up. I'm grinning too. In a more ceremonial setting, the drinking of ava, a brew of dried kava roots, forms part of a traditional greeting. A pig wanders past into the terminal, and then trots back out again. Welcome to Samoa.

Adrift in the South Pacific, for Europeans, Samoa is a paradise you really have to want to visit. A six-hour flight beyond Sydney, or four hours beyond Auckland, this cluster of 10 Polynesian islands and islets between New Zealand and Hawaii won't make a top-10 long-weekend list any time soon. Even their near neighbour, American Samoa, an outpost of US colonial self-interest, keeps its distance through strict visa regulations and a 45-minute flight across the International Date Line to yesterday.

That said, devastation wrought by 2009's tsunami catalysed moves to connect Samoa's South Sea idyll to the world beyond the breakers on the reef. In the same year, to benefit from cheaper imported vehicles, cars switched to driving on the left. A further realignment in December 2011 saw the country vault west over the Date Line to share the working week with New Zealand and Australia. In January 2015 the first international hotel chain made landfall in the shape of a Sheraton (the Starwood-owned brand is also renovating the renowned Aggie Grey's Hotel, founded in 1933 and once popular with actors including Marlon Brando). And, this year, work starts on a 1,300km submarine cable allowing Samoa's Generation Y affordable high-speed internet for the first time.

However, on “the big island” of Savai'i (one-12th the size of Wales), in the unprepossessing village of Satoalepai, new thinking only goes so far. There, 28-year-old Sosefina Sue oversees the village's “swim with turtles” sanctuary while tending various children. “We buy turtles from fishermen who catch them by accident,” she says. I look towards a lagoon where green turtles jostle over slices of papaya. The water is murky. No one is swimming. “What about captive breeding?” I ask.

“The turtles don't breed here because there's no sand,” says Sosefina. “We release two or three when they are ready to lay eggs.” I find it hard to reconcile the sanctuary as anything but a business. “What would you and your brothers be doing if it wasn't for the turtles?” I inquire.

“Samoan people are poor,” she responds flatly. “Only when you go overseas, save some money, then you can start something. Perhaps we will all go to work for some Chinese who come here. I do hate that,” she says vehemently. “This is our land.”

As well as agriculture, tourism and foreign aid, the islands' economy depends on remittances from a large Samoan diaspora, some of whom do eventually return. At Lefaga on the south coast of Samoa's main island of Upolu, the Return to Paradise Resort takes its name from a 1954 Gary Cooper and Roberta Haynes movie filmed on the star-quality beach. Here, beyond graceful palms, a barely credible crescent of perfect golden sand is finally broken by a rocky promontory. Waves of aquamarine collapse noisily on the rocks, relaxing into a tumult of spray and ozone. Breathing in deeply, my lungs are filled by the essence of the South Pacific. It's easy to be dismissive and say “a beach is just a beach”, but if there can be a stretch of coast worth traversing half the world, Lefaga is a strong contender.

After years in New Zealand, manager Ramona Su'a Pale Gilchrist has come home. I talk to her over breakfast, just after an elderly Roberta Haynes herself has visited the newly opened luxury resort.

“Foreign companies wanted to build but the chiefs wouldn't agree. They trust us. We don't own this land. We're guardians,” she says. Land is a recurrent theme, which is understandable on a sprinkling of tiny, fertile islands in a vast ocean. Ramona's son, Raz, adds a footnote: “My grandfather was the first from the district to move to New Zealand. He took the family for a better future. My mother, she promised to bring it back to Samoa.”

In the Apolima Strait, between Upolu and Savai'i, the diminutive island of Manono has a population of 1,200, seven churches, no roads and no cars. Electricity arrived only recently. Under the shade of a thatched fale, 82-year-old Loaka is weaving traditional fine floor mats. “What's changed the most in your lifetime?” I ask. She stops threading palm fibres and considers the question. “Nothing much,” she says. “Just the attitude of the teenagers.” I walk on through the village, past papaya plants, trees laden with oranges, and blue arrows pointing the way to run in case of a tsunami.

I'm staying at Sunset View Fales, simple beach bungalows built among exotic blooms and verdant shrubbery on a steeply rising hillside overlooking a small bay. After dumping my bag I'm invited to join Apa Lagaali who's busy preparing an umu earth oven. Scattering sundry chickens, I find Apa and three foreign guests under the tin roof of a smoky shelter.

“I'm from Upolu,” says Apa as he casually splits a coconut.

“How did you come to be here?” I ask.

“Via a lady …” he says. “We can choose where to live but the land stays with my wife. I spent '75 to '79 working in New Zealand, but I don't like getting up in the morning. It's better here.” A silence falls.

Apa shows how to scrape flesh from a coconut, how to squeeze coconut cream through husk fibres, and how to make taro leaf parcels ready to cook on the umu's hot rocks. “We use every part of the coconut, and this,” he points to the wrung out coconut shavings, “the pigs and the chickens will eat.”

Displaying effortless dexterity that comes from years of practice, in seconds Apa fashions a plate from palm fronds. “Making baskets, plates …” he says. “The kids, they don't know how to do it. They use your pelagi [foreign] plastic plates.”

After we've eaten Apa produces a rudimentary firestick and, in no time, creates a glowing ember and lights his cigarette. “Maybe I'll show him,” he says, pointing to a small boy. My inner Ray Mears clamours to have a go too. I squat down and rub the sticks furiously. I get sweaty, feel slightly sick, make a wisp of smoke, and that's all.

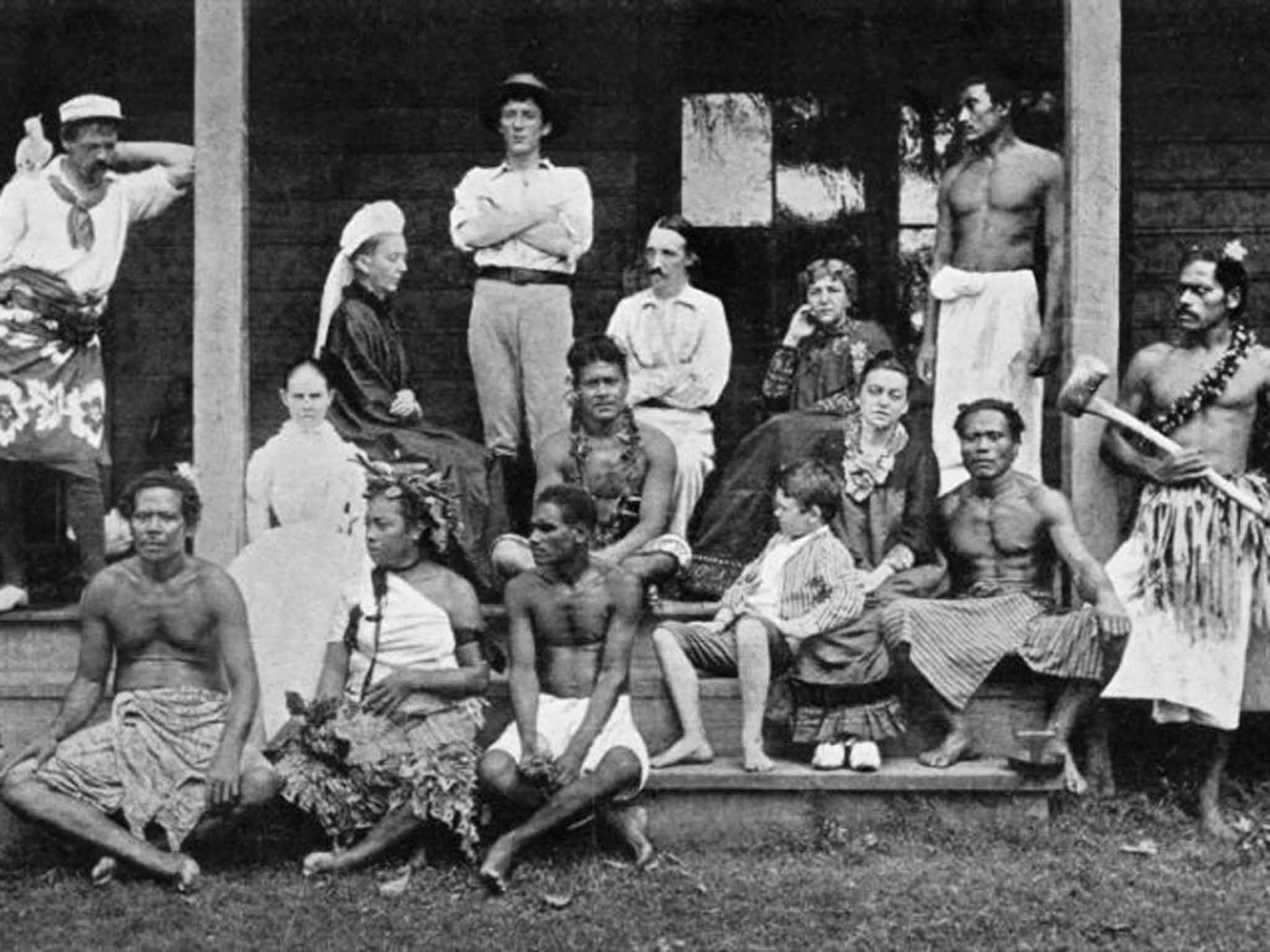

Samoa's society, its structure and boundaries as defined by the traditions of the fa'a Samao – the Samoan way – has been preserved in the inert atmosphere of splendid isolation. Robert Louis Stevenson spent his final years in Samoa, determining it to be the place “I have found life most pleasant and man most interesting.” However, he also observed that “change of habit is bloodier than bombardment”.

The luxury of staying apart and remaining the same no longer appears to exist. That the country's 190,000 inhabitants look to New Zealand, a nation of 4.5 million, as their major economic partner puts the delicate balance of Samoa's macro-economics in perspective. Navigating the course of future development is no easy task and unlike the tsunami signs, directions are much less clear.

Getting there

Cox & Kings (020 3642 0861; coxandkings.co.uk) offers 12-day/ nine-night holidays to Samoa from £3,595pp, including flights from Heathrow via Auckland, accommodation at the Sinalei Reef Resort, Le Lagoto Beach Resort, and Tanoa Tusitala Hotel, transfers, tours of Eastern Upolu, Apia, and return inter-island ferry.

More information

Nick Redmayne travelled courtesy of the Samoa Tourism Authority (00 685 63500; samoa.travel)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks