Kimberley: Exploring Western Australia's spectacular landscape by sea

Mark McCrum climbs aboard a new ship for a close-up view

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a backpacking trip around Australia 20 years ago, I had to miss out on the legendary Kimberley. This vast wilderness in Western Australia's far north, where just 41,000 people are scattered across an area three times the size of England, was just too hard to access. Even the unsurfaced Gibb River Road, which plunges deepest into the region and is one of its two major arteries, is more than 100 kilometres from the natural wonders of the coast.

But now, I was finally getting a chance to see it, aboard the Silver Discoverer, which launched earlier this year as the eighth vessel in luxury operator Silversea's fleet. She is the third of its "expedition" ships, which are comparatively nimble vessels that can reach places larger liners cannot. Carrying just over a hundred passengers, they are kitted out with rigid inflatable Zodiacs. So the guests (as they are known) get the best of both worlds: all the comforts of five-star cruising – with the added frisson of a daily adventure out.

Lifeboat drill up on deck gave me a chance to check out my fellow passengers: mostly retirement-age Australians in a fine range of colourful shirts, vests and hats; but as we set sail from Broome and cocktails were served in the Explorer Lounge, it was clear from the noise levels that they were anything but retiring.

A loud "shh" announced marine biologist Mick Fogg, our expedition leader – a courtly Australian who bowed and smiled and addressed the ladies as "ma'am" before introducing us to his 12-strong expedition team. All of them were experts in an aspect of the wildlife or the landscape that we would be passing through on our 10-day journey north-east towards Darwin. "You are going to fall in love with the Kimberley region," he concluded. "Particularly the rocks."

At breakfast, while we were anchored in Yampi Sound, I began to see what he meant. Rounded cliffs of gorgeous orange sandstone were reflected in a glassy sea. By 9am, we were hatted and sunblocked and disembarked into the Zodiacs. My boat, Beagle, was captained by Uli, a German geologist, who explained that the rocks before us were 1.8 billion years old. "People ask, 'Are there fossils in there?' But there were no creatures at that time."

Close up, this orange, white and dark grey rock was striated in curving layers, visibly bent and buckled, he explained, from when two continents collided. "And now," he added, as we passed a three-metre high, conical termite mound, "a dinosaur dropping".

We crossed the bay in a convivial mood for a swim in a freshwater pool at the alarmingly named Crocodile Creek (which had been thoroughly examined for any lurking salties beforehand). An overnight sail then brought us to Talbot Bay, where taller wooded cliffs made a dark early shadow against the brilliant surrounding blues.

Our excursion that morning was to Horizontal Falls, where massive tidal flows race through two narrow gaps in the cliff, creating a pair of flat waterfalls, described by David Attenborough as "one of the great wonders of the world". With a neap tide the Zodiacs were able to speed through both, into an enclosed bay where we came, suddenly, upon our first crocodile, semi-submerged in the still water, eyes and jaw just above the surface, four metres of greeny-black scales bobbing menacingly behind.

"Is he real?" asked one of the ladies. "No, he's battery-powered," joked another. But even as they snapped away with their cameras, the apprehension was tangible. We were all relieved to be powering back through the swirling white water to the open sea beyond. Here, on the cliffs, we found less threatening wildlife: a brahminy kite, a white-bellied sea eagle, and perched high among the orange rocks, a short-eared rock wallaby, standing up, paws forward.

By lunchtime, we were on our way again, the gentle creaking of the ship sounding like distant rain. As we sailed north-east past Doubtful Bay and Camden Sound, I treated myself to afternoon tea: three tiers of sandwiches and cakes, with flying fish visible through the porthole windows.

We were up at 6.30am, for a five-hour Zodiac ride up the Prince Regent river to King's Cascades, a waterfall above a still, dark pool. After we'd paused to admire another croc, this one sunning himself on a rock with his mouth wide open, Mick told us the horrific story of Ginger Meadows, a young American model who, having watched Crocodile Dundee in 1986, decided to visit Australia. She hitched a ride around this coast on a yacht and went swimming in this very spot. She was attacked by a lurking saltie and dragged beneath the surface, in the infamous "death roll", as her friends watched helplessly.

We were all glad to get back to the ship after that. We sailed at noon, arriving at mid-afternoon at Careening Bay, where the explorer Phillip Parker King once parked up to repair (careen) his ship. Just above the long sandy beach is a giant Baobab tree, on which his sailors had carved: "MERMAID 1820". Two hundred years had passed, but in this timeless, empty landscape it felt like they could have been here just a few weeks ago.

I woke the next morning to find a pink dawn glow on the orange cliffs at the mouth of the Hunter River – a spectacular backdrop for breakfast on deck. Later, Australian naturalist Brad took us out for a well-informed buzz around the mangroves, set against a much lusher rainforest landscape than before, with green vines tumbling down over figs and eucalypts to the water's edge. Sandpipers, reef egrets, whimbrels, and then, warming himself on a rock, a half-metre Mertens' water monitor.

A second trip at low tide brought out manta rays, cruising through the shallows like underwater flying saucers. Up on the gleaming mud were mudskippers, 15cm fish that can climb trees, pulling themselves up with fins that act as rudimentary elbows. And then, further up the river, no fewer than three three-metre salties, jaws wide open to reveal fearsome teeth and pinky-yellow mouths. They were in defence mode, Brad told us; or else just keeping cool in the fierce afternoon heat. Cold-blooded as they are, salties have to thermo-regulate their body heat to 32C.

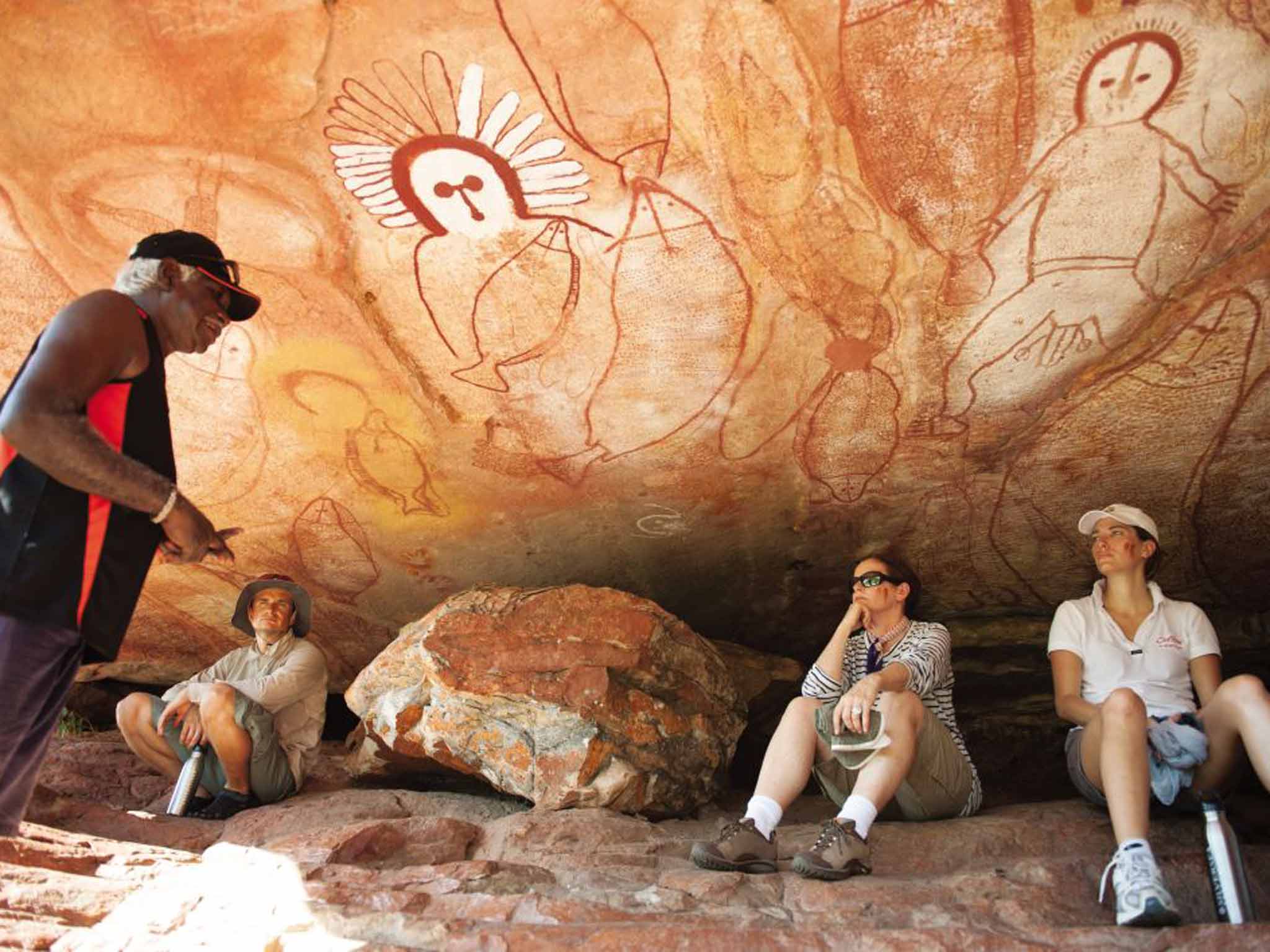

Swift Bay brought us something I'd failed to see in eight months as a backpacker: Aboriginal rock art, in two caves right by the water's edge. No restrictions, no interpretative centre, just moor the Zodiac and walk up 50 metres past the middens of crushed shells. And there, under an overhang, were petroglyphs in white, black and sienna – dating back anything between 5,000 and 17,000 years – of birds, fish, turtles and Wandjina, the Aboriginal spirits who created the land and controlled the weather. Mouthless, with huge eye sockets, and hair like some strange head dress, they emanated a horribly ghoulish feeling even from these simple outlines.

"Don't touch them," Mick told us. The one time he'd experienced bad weather in the Kimberley was when someone had put a finger on the place where the Wandjinas' mouths should be.

He was surely joking, but when we arrived the next morning at the mouth of the King George River, 100 or so kilometres on, it was heaving with tropical rain. The six-hour trip to King George Falls that I'd signed up for over briefing drinks the night before suddenly seemed less inviting. But the rain was warm, and the ride up the river was spectacular. And, as the downpour eased, out came the birds.

"A jabiru!" shouted Malcolm, the ship's bird expert, pointing out a black-headed creature mincing along by the reeds on long red legs. Then a Jesus bird, which walks on weed; the female lays the eggs and clears off, leaving the chicks in the care of the male – there were a few jokes in our Zodiac about that, as you can imagine.

Miles of spectacular striated orange gorge, then, turning a corner, a huge double waterfall, 80m high, still fast-flowing from the wet season. The trek up to the top involved a steep climb to one side of the falls, to reach a rocky plateau dotted with pink coastal hibiscus.

I had to hand it to my fellow guests, they were very game, hauling themselves up over these slippery red boulders as if they were fifty years younger. Then, gasping as they reached the top, agreeing that the view made it all worth it. As the rain streamed down again, bouncing in fat drops off the surface of a clifftop billabong, they were stripped down and swimming, every bit as boisterous in their Speedos as at cocktail hour.

There were three days ahead, with scenic flights over the spectacular domed rocks of the Bungle Bungles for some, and a cruise up the bird-rich Orde River for others, before we finally docked in Darwin. But these were trips that any tourist to the Northern Territory can do. Today was our last day of the very special access the Discoverer and its Zodiacs had granted us and it really didn't get any better than that.

Wilderness adventure by day, then cocktails and a four-course dinner on the gently rocking ship by night. It had been worth waiting this long to see this coast properly, in a way that that youthful backpacker could never have managed on his own.

Getting there

Mark McCrum travelled with Malaysia Airlines (0871 423 9090; malaysiaairlines.com), which has four connections a week from Heathrow to Darwin via Kuala Lumpur, from £692 return in May. Flights to Darwin are also offered from Heathrow by Singapore Airlines, connecting in Singapore with its subsidiary Silkair.

Cruising there

Silver Discoverer departs on 9 April 2015 for a 10-day voyage along the Kimberley coast from Broome to Darwin. Prices start at £6,550pp based on double occupancy of an Explorer Suite (0844 251 0837; silversea.com).

More information

Mark McCrum's novel 'Fest' is published by Prospero Press (£7.99; prosperopress.net)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments