The Experts' Guide To The World: Beijing

Once you get out of the Beijing suburbs, the road takes you through the hills, an increasingly dry landscape as you head north along a dusty, winding course. After just 50km, you are in a craggy, mountainous area where the breakneck expansion of the Chinese economy has no influence – more like the China we know from the long, shimmering ancient tapestries on silk.

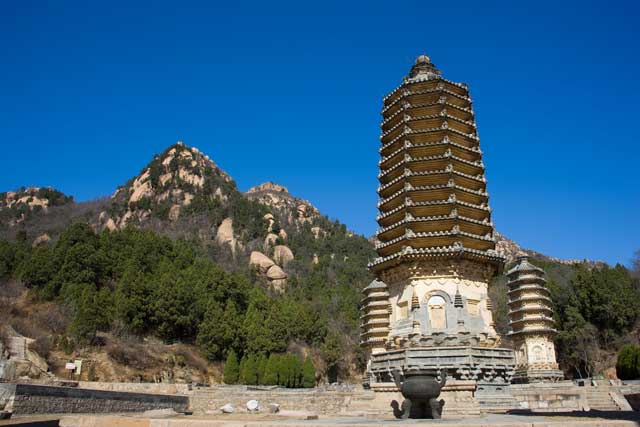

Here there are lofty peaks, fabulous sections of Great Wall, improbably poised boulders and a gathering of elegant pagodas – the 18 surviving stupas all that are left of the Fahua Temple. This whole area was once dotted with 72 Buddhist temples during the Ming and Qing dynasties and was a crucial place of pilgrimage.

As early as the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD), this area was used for Buddhist rituals. The temple was badly damaged by the invading Japanese army in 1941, and the pagodas must have come in for abuse by zealous Red Guards during the ideological extremism of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

These crumbling edifices would be beautiful all by themselves, but their setting against the imposing peak of Yinshan behind is what makes the area really special.

Yinshan, or Silver Mountain, is close to some of the staggering sights near Beijing, including the spectacular Huanghuacheng section of the Great Wall, which dips into the ocean, and the Ming Tombs. Its name derives from the silvery sheen of the snow on the mountain in winter. While not far enough from Beijing to escape the pollution entirely, any time I've visited, it's been clear.

Silver Mountain is a reasonably popular tourist spot, but not uncomfortably so. You see some older visitors who come to the site to do three clockwise, three anti-clockwise turns around one stupa – a mushroom-shaped building where the monk Deng Yinfeng gave lectures on Buddhist doctrine. It's supposed to help with pain in your waist or legs. It can also ward off evil. At Yinshan's base, meanwhile, hawkers sell bags of delicious Chinese dates. But it's not overrun with people pedalling the kind of knick-knacks you get elsewhere around the Great Wall – popular right now are T-shirts that superimpose President Obama's face on to a Socialist Realist depiction of Chairman Mao – Oba-Mao.

The ascent is about an hour's walk if you're fit, a bit longer if not, and there are steps to make it less perilous. In summer, around half way up you can buy a lolly from a woman who brings up large blocks of ice to keep things cool. The hike to the summit is through pine and cypress groves, pear and chestnut trees, copses of walnut trees, and you pass various Buddhist ruins on the way. At the top, as a red flag flutters in the breeze, there is a real camaraderie between those who've made it. It's a robust challenge, but doable with small children, and Chinese families at the top like to share food and gossip.

There are great places to stay, too, such as the Xiao Yong Gu hotel, near Haizi village in Chongping district, which has a Japanese-style onsen spring bath and terrific walks through the stone-walled fields around the farm. After hiking up Yinshan, it's fabulous to have a fiercely hot soak in the bath, and they cook home-style food – duck with pancakes, vegetables from the garden, and steaming jiaozi dumplings for lunch the next day. In fact, it gives you enough energy to start thinking about doing it all over again, before heading back to the city.

Clifford Coonan is Beijing correspondent of The Independent

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks