The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How to explore Gandhi's Delhi 70 years after his assassination

Tamara Hinson signs up for a Gandhi-themed exploration ahead of the 150th anniversary of the activist’s birth

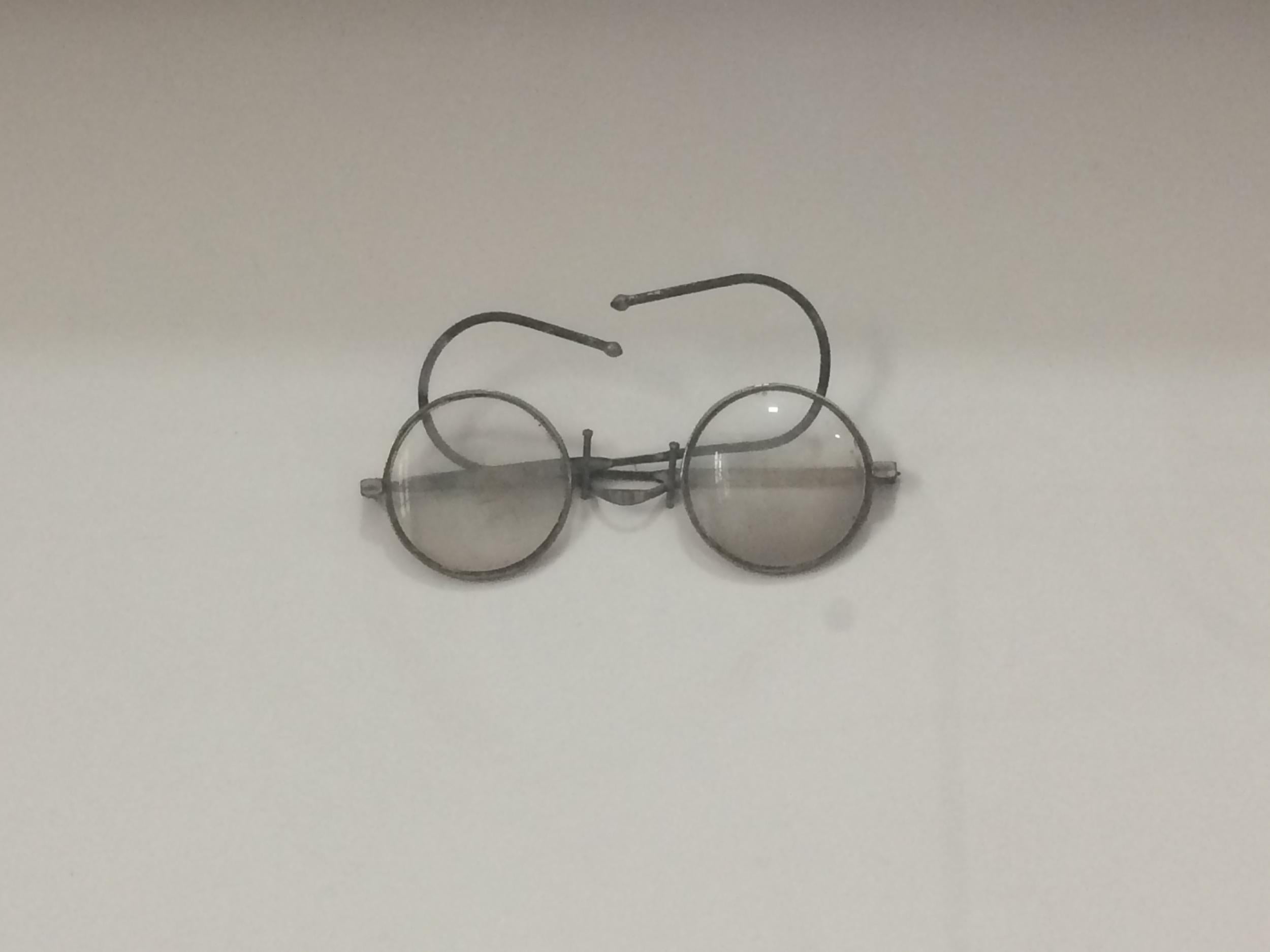

Wandering through the Delhi mansion in which Mahatma Gandhi spent his final days, I can’t help but feel it’s slightly ironic that 2018 marks not just the 70th anniversary of his assassination (next year will mark the 150th anniversary of his birth) but the start of the #MeToo movement. What Gandhi, often referred to as the leader of the Indian independence movement, would have thought of it all remains a mystery. The bespectacled activist was regarded by many, both during his life and after his death, as a feminist, something backed up by a framed quote at Gandhi Smriti in which he urges women to fight back against aggressors: “God has given her nails and teeth. She must use them with all her strength.”

But depressingly, like so many other famous figures, Gandhi’s reputation has been tarnished since his death – revelations surfaced that he forced young girls to share his bed. He also openly admitted to seeing black people as inferior. Many believe this latter belief stemmed from one of the key incidents which shaped his life.

In 1893 Gandhi, who spent several years studying law in London, was thrown out of a carriage on a train in South Africa due to the colour of his skin. But it’s been suggested that what infuriated him the most was that, as an Indian, he was seen as “little better, if at all, than savages or the natives of Africa” – a phrase included in a letter he wrote to the Natal parliament the same year. Nonetheless, the incident, which took place two decades before his return to India, sparked a lifetime of social activism, summed up by another framed quote relating to his disdain for the caste system (still prevalent in parts of India), decreeing that parents should “cease to be dazzled by English degrees and should not hesitate to travel outside their little castes”.

There are several Delhi sites connected with India’s most famous activist, but Gandhi Smriti is the most significant. Formerly Birla House, it was owned by businessman Ghanshyam Das Birla, who persuaded Gandhi to stay in his home (despite his wish to reside in the slums). In 1948, Gandhi was assassinated by a right-wing Hindu nationalist who believed that he favoured India’s Muslims during the partition of India.

He was shot shortly after leaving his bedroom to walk to a nearby prayer meeting. Today, the spot is marked by a small memorial, and stone footprints set into the grass mark his final steps. Nearby, in his simple bedroom, time stands still – next to his mattress and pillow is his pocket watch, stopped at the time of his death.

In the Eternal Gandhi Multimedia Museum, housed in another part of the building, I discover exhibits designed to provide a more hi-tech insight into his life. Behind a huge sheet metal cast of his face are LEDs that light up his famously bespectacled eyes, and there’s a row of replicas of his famous walking sticks – information about different aspects of his life appears depending on which one I pull. In another room, I find the Unity Pillar. When my friend and I sit either side and touch hands, the structure magically lights up, a reminder of Gandhi’s belief that challenges are easily overcome when people unite. There are tributes to his love of music too, including a Gandhi-shaped swarmandal (Indian harp), topped with a piece of wood resembling the shape of his bald head.

The nearby colourful, art-like display of weaving machinery is a reminder that Gandhi was a dab hand with a loom. He was a firm believer that to establish autonomy from Great Britain, India needed to end its reliance on imported cloth. For Gandhi, spinning, using a simple wheel (or charkha) became a non-violent form of civil disobedience and a symbol of the Swadeshi movement, which aimed to improve economic conditions through the boycotting of British products and the creation of India’s own textile industry.

The charkha, which appears on India’s flag, is regarded as such an important part of the country’s independence that there’s an entire museum dedicated to it. You’ll find the Charkha Museum, which opened last year, near Connaught Place in the city centre. I discover a huge collection of spinning wheels, including an enormous, 26ft long version (the world’s largest) and smaller, portable ones. Admission sets me back 20p, and I’m allowed to keep my ticket – a laminated card bearing one of Gandhi’s quotes, tied with a piece of multicoloured cotton made by female prisoners from New Delhi’s Tihar prison.

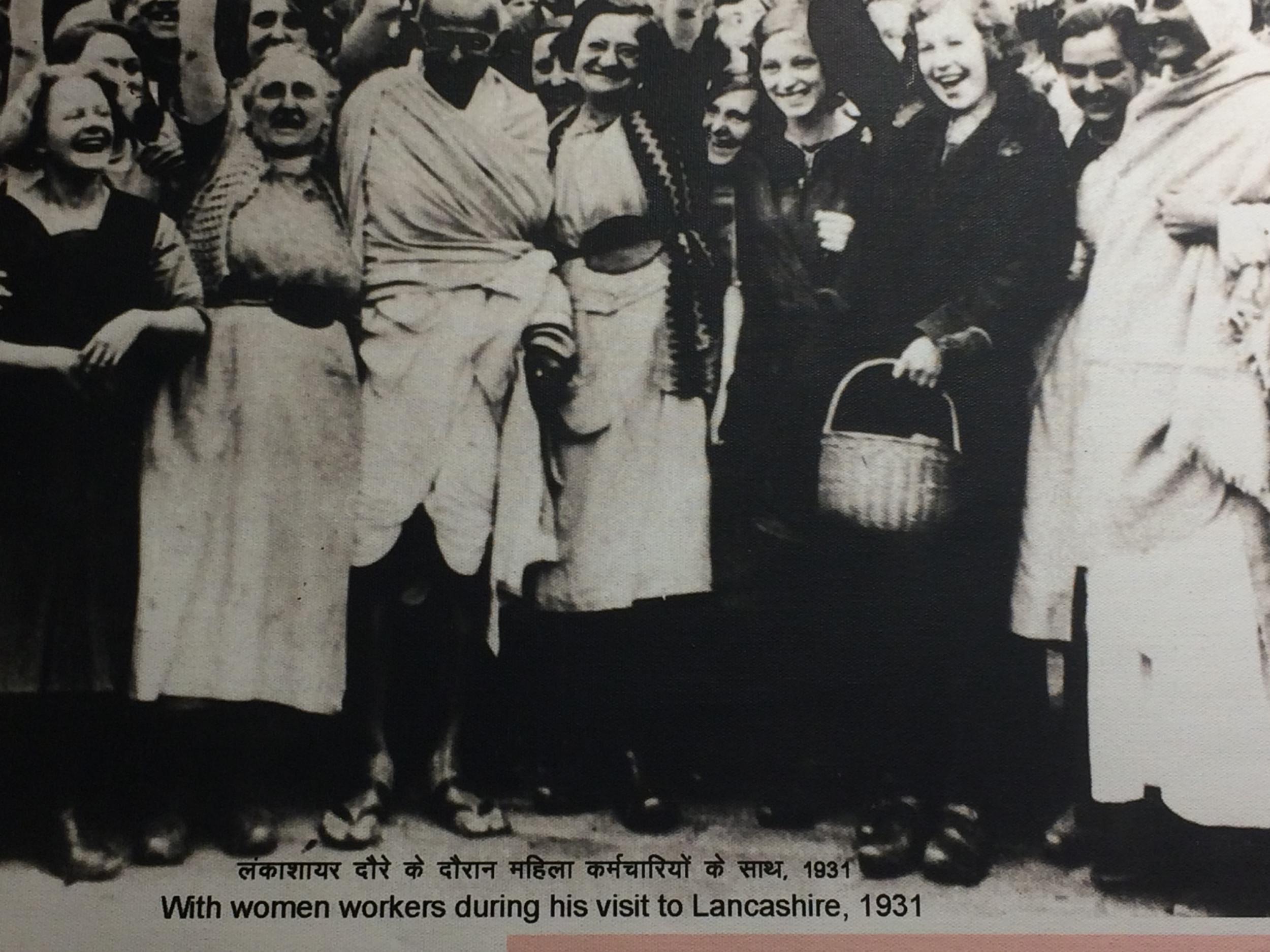

My final stopoff is New Delhi’s National Gandhi Museum. One of the most striking exhibits is a photo of Gandhi standing with weavers in the Lancashire town of Darwen. He’d been invited there by the mill-owning Davies family, who wanted to show how India’s campaign for independence had left British workers destitute. The plan backfired – when one Lancashire local complained about the lack of work, he replied: “My dear, you have no idea what poverty is.”

You’ll find this photo near the one of him sitting next to Charlie Chaplin, and a few metres from the one showing him inspecting produce at Islington’s Royal Agricultural Hall. There’s also a huge collection of stamps – in 1949, he adorned 32 million, printed to mark what would have been his 80th birthday. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given his views about the Indian economy, there was uproar when it emerged that a Swiss firm had been commissioned to print them.

Nearby, behind a sign asking for silence and next to the bullet which killed him, there’s the bloodstained sari he was wearing when he was assassinated. Gandhi might be long gone, but the stream of visitors paying their respects is a reminder of Indians’ enduring respect for the complex man who fought for their country’s independence. Today, Indian law states that the country’s flag must be made of khadi, the hand-woven fabric he championed. It’s a fitting tribute to the country’s most famous, if flawed, activist.

Although the Gandhi-shaped harp certainly comes a close second.

Travel Essentials

Getting there

Virgin Atlantic flies from London Heathrow to Delhi from £375 return.

Staying there

Doubles at Shangri-La’s Eros Hotel from £94, room only.

More information

Urban Adventures’ three to four-hour Gandhi’s Delhi tour costs £47 per person.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks