Mount Vernon, Virginia: George Washington and the slaves who kept his estate running

The 21st-century Mount Vernon is much more than an old house to traipse around

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It looks like a particularly austere hostel dormitory. Wide, basic but sturdy wooden shelves line up against the bare brick wall. Dividing panels split them up into separate beds, and thin sheets provide the most basic of cover. Elsewhere, there are cooking utensils used to feed all with ration-stretching one-pot meals, and stools where the older women would perch for hours at a time while sewing or spinning.

The recreated slave quarters at Mount Vernon are ascetic without falling below the line into the realms of callously grim. From a slave's perspective, there will undoubtedly have been worse plantations, but there will also have been better. What makes this one so significant is who it belonged to – a man who could have ended slavery long before it was finally abolished.

On 18 December 1865, the 13th Amendment became part of the United States Constitution. It outlawed slavery in a country that had been almost riven in two by the issue. Mount Vernon was on the very edge of that North-South line, just in slave-owning Virginia but a few miles down the Potomac River from slavery-free Washington DC.

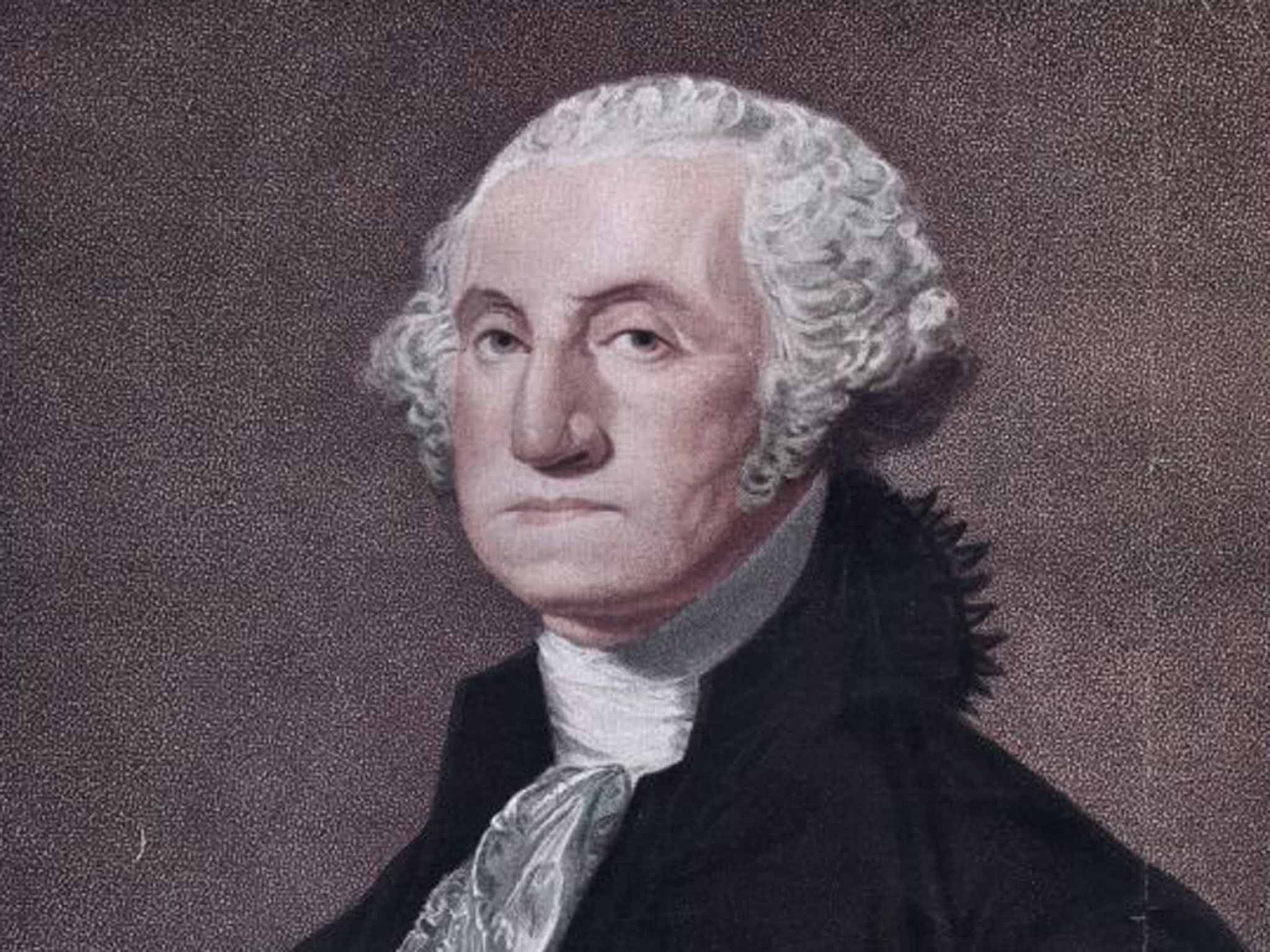

George Washington inherited the Mount Vernon estate in 1761, and set about turning it from a simple dwelling on 2,000 acres to a 21-room mansion on an 8,000-acre property. It started as a tobacco plantation, but Washington switched his main crop to wheat in 1766, when tobacco was no longer financially sustainable.

The vast majority of the work on the plantation was done by slaves, and when Washington died there were 316 of them living on the estate. He was by no means the only US president who owned slaves – at least nine of them did – but as the first president of the new nation he had more power to shape its path than most. He set precedents for presidents serving only two terms, being addressed as “Mr President” (other proposed options included “His Excellency”), and giving the annual State of the Union address as a speech to Congress.

On slavery, though, he equivocated. There's a wealth of evidence to suggest that Washington became more firmly against slavery as he got older, and he did free his slaves in his will when he died. But fear of splitting the infant nation seems to have won out over doing the right thing while he was president.

The 21st-century Mount Vernon is so much more than an old house to traipse around, admiring period furniture that belonged to the Washingtons. Visitors have formal gardens, a distillery, a gristmill, a small sample farm with livestock, a museum and education centre, plus all manner of themed tours to tackle. Of the latter, there is one devoted to Washington and slavery – which is rather commendable given that Washington's status as a great hero plays a large part in drawing in the vast numbers who visit every year.

The guide paints a picture of Mount Vernon as a home to a community of enslaved people. And they were a community; Washington encouraged marriage and having families among the slaves, although how altruistic that was – more children means more slaves, and family attachments meant slaves were less likely to run away – is a moot point. However, they weren't treated purely as tools. Around 40 per cent were too old, young or infirm to contribute, but were looked after rather than being turfed out.

A lot of what is known about Washington's treatment of his slaves is pieced together through his letters. In one, he admonishes an overseer for viewing slaves “in the same way as beasts in fields”. But in another he backs a manager for whipping a slave named Charlotte, saying: “If they refuse to do their duty or are impertinent, they must be corrected.” Washington also liked his slaves to work as hard as he did – which meant from daybreak to sundown six days a week.

The guide talks of letters that reveal Washington's change in attitude towards slavery. In one, written just after the War of Independence, he vows to a friend that he will never buy another slave. There are also accounts of his failed attempts to sell slaves to people he knew would set them free.

Walking back to the slave quarters, though, a sense of plodding routine comes through. It's the two outfits a year; the dull but meagre food rations supplemented by hunting and fishing on the estate; the six-mile round treks undertaken at night by men going to see their families on other farms further from the mansion house.

The tales of deliberately breaking tools, feigning sickness, and attempted escape dispel any desperately misguided notions that life as a slave at Mount Vernon was a happy one.

Separated from the mansion by a patch of woodland is the slave cemetery, which is now the site of an archaeological dig. Machinery churns through the soil in an attempt to find out more about the men and women who kept the first president's estate running. Had they been freed to live out their lives and die elsewhere, American history may have run a very different course.

Getting there

David Whitley flew with British Airways (0344 493 0787; ba.com) from Heathrow to Washington Dulles. Mount Vernon is 15 miles south of Washington DC. Take the Metrorail yellow line to Huntington Station, from where the 101 bus connects to Mount Vernon.

Visiting there

Mount Vernon (001 703 780 2000; mountvernon.org). Entry, including the slavery tour, costs $17 (£11).

Staying there

Hotel Monaco (001 703 549 6080; monaco-alexandria.com) in nearby Alexandria has doubles from $164 (£109) a night, room only.

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments