Inside the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum that's tackling American racism head on

The new museum provides an unflinching account of the state’s shameful history

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Blood still stains the driveway of Medgar Evers’s home in Jackson, Mississippi.

It’s soaked into the flagstones where the 37-year-old civil rights campaigner – who led efforts for desegregation and black voter registration in America’s South – fell to the ground on 12 June 1963, shot in the back by a sniper’s bullet as he unloaded his car.

The murder weapon is now displayed at the new Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, among other emotive exhibits that hold a mirror up to the state’s history of racism.

Located five miles from Evers’s home, the museum opens on 9 December alongside the new Museum of Mississippi History, with which it shares a lobby. The joint launch is no coincidence – the two museums’ overlapping topics of slavery, the American Civil War, Jim Crow segregation laws and the Delta blues provide a comprehensive and unflinching sweep of Mississippi’s history.

It’s not the first time the state has confronted its history of racism head on. From 2011, a series of “Freedom Trail” markers were placed at sites across Mississippi, including Evers’s home. But the trail has been blighted by controversy – two markers associated with Emmett Till, whose lynching galvanised the civil rights movement, were vandalised, in an ugly reminder that racism is alive and well in the Southern state.

Those behind the new Jackson museum, which is the country’s first state-funded institution dedicated to civil rights, are determined this history should no longer be ignored.

“It’s a good thing for the state of Mississippi to show its darkness,” says museum director Pamela Junior, who was born and bred in Jackson and describes Mississippi as “ground zero” for civil rights. “If we can show, with authenticity and truthfulness, the history of the state, then we are making amends.”

It’s a timely move. Against a backdrop of far-right rallies and accusations of police brutality, a recent poll showed 70 per cent of Americans believe race relations are poor in the US. The Confederate flag – already removed from government buildings in Alabama and South Carolina because of its racist symbolism – is still part of the Mississippi state flag.

“Racism is here and it’s alive,” says Ms Junior. “It is in most places. But there are also people who want change.”

In 2011, a team including lead designer Richard Woolacott interviewed Mississippians, both black and white, about what they wanted from the museum. Overwhelmingly, they responded that they wanted the truth – no matter how harsh.

“There was a feeling that the state would whitewash events,” says Mr Woolacott, who worked alongside architects Perkins+Will. “It needs to be real, and it needs to be the voices of people who lived it.”

Abutting the history museum’s colonnades, the sepia facade of the civil rights museum is etched with overlapping lines forming an ‘M’ shape, reflecting brutal clashes between activists and police.

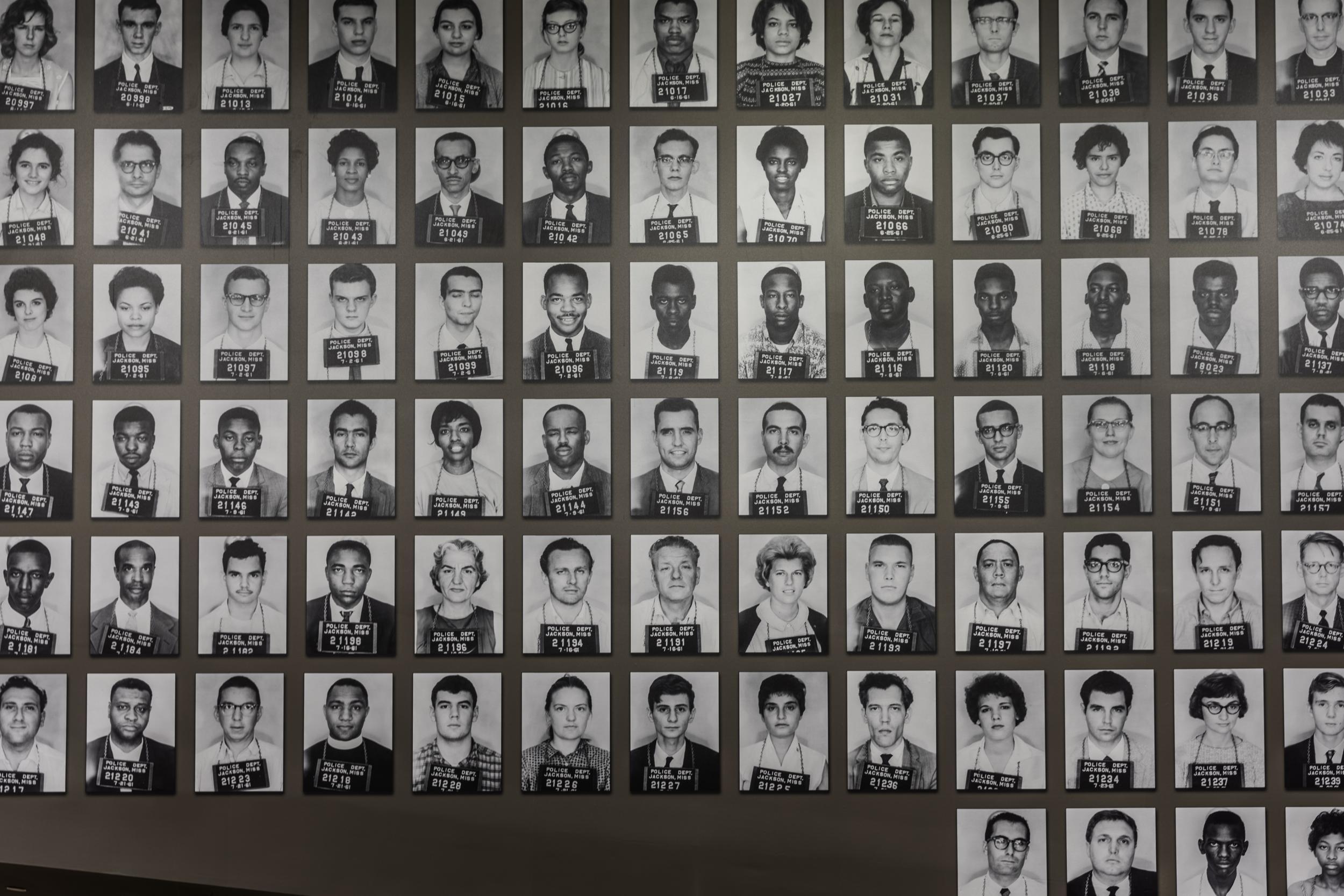

Inside, mugshots of Freedom Riders cover an entire wall in one gallery. Arriving into Jackson to protest against segregated bus depots in August 1961, they were rounded up and thrown in jail. “Some of them died so people like me could vote,” says Ms Junior.

Throughout the museum’s eight large galleries, intimate objects jolt the past into the present. There’s a Freedom Rider’s faded flip-flops, and the remains of a charcoaled cross, torched on the lawn of a white family who dared to support the civil rights movement. The brutality is palpable, as is the scent of death. A single crumpled, sooty door of a pickup truck is the chilling remnant of the Ku Klux Klan’s deadly firebombing of civil rights leader Vernon Dahmer’s home in January 1966.

Visiting the museum for a private viewing in November, Dahmer’s widow Ellie said the museum showed Mississippi had “come a long way”. “We lived it. Some of them died with it. The rest of Mississippi needs to know about it,” she told reporters.

Mississippi was infamously the location for some of the greatest outrages of the civil rights and Jim Crow era. A pair of scuffed, whitewashed doors has been rescued from the crumbling Bryant’s Grocery Store in Money, 100 miles north of Jackson. Fourteen-year-old Emmett Till walked through these doors in August 1955, when he was said to have whistled at white shopkeeper Carolyn Bryant (decades on, she admitted inventing the accusation).

He was abducted from his great-uncle’s house a few nights later, and tortured, killed and dumped in the Tallahatchie River.

The incident became a turning point in American history when Till’s mother held an open-casket funeral and invited journalists to photograph the boy’s body. It’s still so raw even Pamela Junior struggled to face the exhibit. “I could feel it, that Emmett touched those doors. I couldn’t go in.”

Vertiginous monoliths, listing the names and ‘crimes’ of lynching victims, stab through each gallery. It’s intense – almost unbearable – as it’s supposed to be.

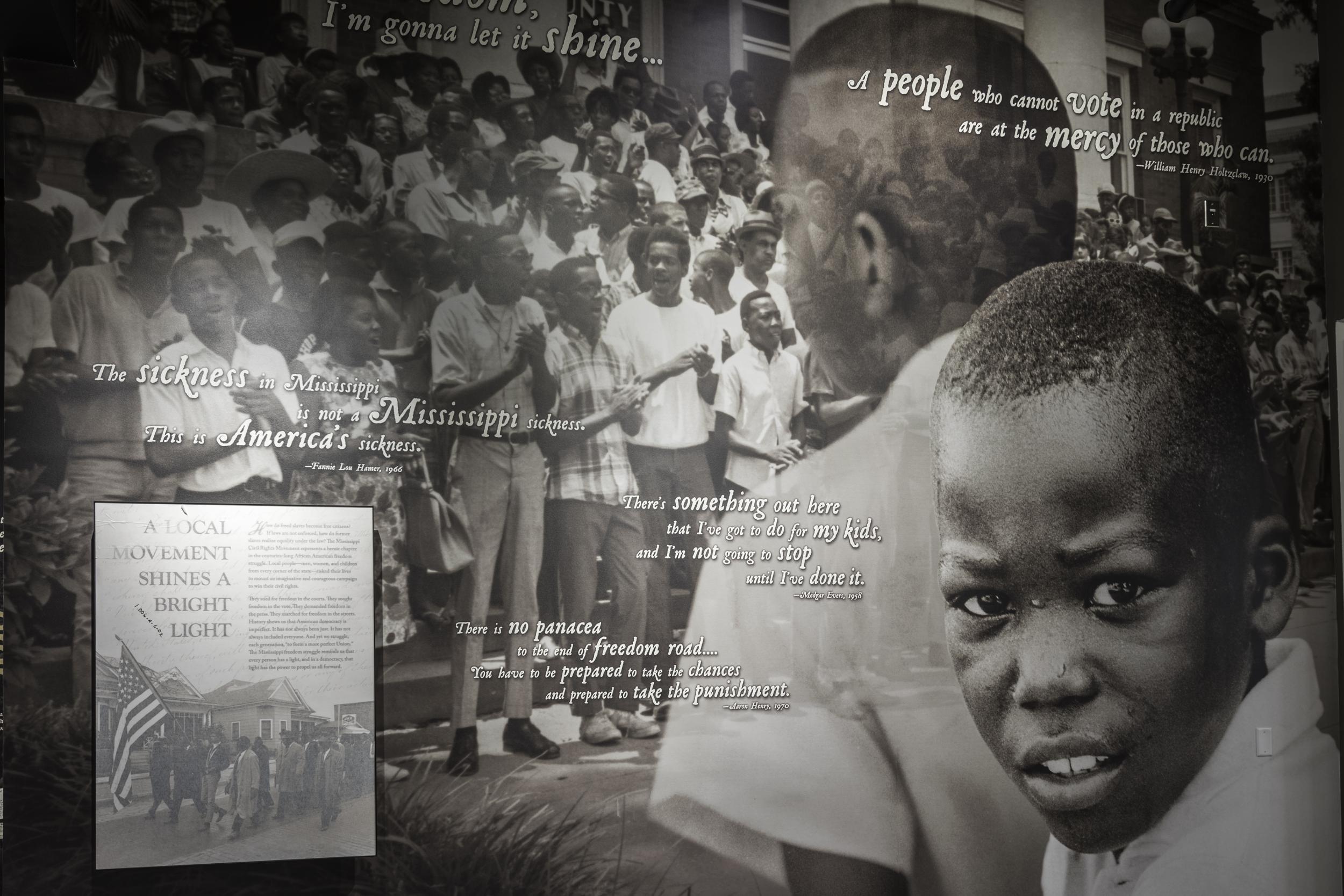

The galleries encircle a central room, This Little Light of Mine, which has photographs of civil rights heroes soaring to the ceiling. An installation sends tendrils of light into the other rooms, illuminating dark corners with a shimmer of hope as the civil rights anthem of the same name gets louder as people gather in the space.

Inside Medgar Evers’s home – which opened as a museum in 2013 – curator Minnie Watson runs her fingertips over a deep hole outside the family’s kitchen. The fatal bullet tore through Evers’s body, sliced through the window and pierced this wall, finishing on the kitchen counter. Yet many residents of Margaret Walker Alexander Drive stayed silent in the aftermath.

“People around here were afraid,” Ms Watson says. “They didn’t talk about it. One woman told me, ‘They would kill you or call you crazy’.” It took 31 years for white supremacist Byron De La Beckwith to be convicted of Evers’s murder.

As current headlines coming from the US attest, there’s still work to be done, but Pamela Junior believes facing history can help the state to heal.

“We have to choose how we represent ourselves, in Mississippi and all over the world,” she adds. “Now is our time.”

Travel essentials

Getting there

Virgin Atlantic and Delta codeshare, so you can fly from London to Atlanta on Virgin and on to Jackson on Delta from £748.

Staying there

The Fairview Inn has doubles from £150, B&B.

More information

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum opens on 9 December. Entrance is $8 (£6), or $12 (£9) including the Museum of Mississippi History.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments