Flinders Island: Cast away in Tasmania's 'last Eden'

Flinders Island was named after the Englishman who first charted it and who coined the term 'Australia'. And, as James Stewart finds, it has changed little since then

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A40-minute flight over the Bass Strait can see you land a few decades from modern-day Australia. Or so a Melbourne radio station had told me prior to my arrival on Flinders Island. The feeling that this Tasmanian outpost might be a world apart had been growing ever since my tiny plane taxied from an oversized shed at Launceston airport instead of the main terminal. And it seemed a throwback when the car hire manager in the capital Whitemark (population 200) said there was no need to lock your vehicles anywhere on Flinders – one islander left his keys in the ignition, she added, because "you never know when someone might need to borrow the car".

However, it wasn't until the car radio, tuned to ABC Melbourne, reported traffic snarled for miles on Melbourne's freeway that modern Australia vanished over the horizon. I hadn't seen a car for hours; just furry backsides bouncing into the bush and eagles silhouetted in an empty sky. The sense of being cast away in rolling seas was exhilarating.

Matthew Flinders, the island's namesake, surely would have sympathised. Inspired to join the Royal Navy in 1789 by Robinson Crusoe, he is probably the greatest British navigator you've never heard of; his life of supreme skill, heroic endeavour, and capture by French rivals, as adventurous as any yarn by Daniel Defoe.

Yet it wasn't until last week that Britain saluted its forgotten hero in public. Unveiled by Prince William at Australia House exactly 200 years after Flinders died on 19 July 1814, the first statue of the adventurer in this country now stands on the concourse of Euston Station in London (his grave is thought to lie beneath Platform 15). Beneath the Arrivals board, he crouches over a chart with his navigational dividers and pet cat, Trim.

The chart depicts the continent that made him – Australia. Born in 1774, Flinders embarked to New Holland (as Australia was known) as a 21-year-old naval lieutenant. He charted the New South Wales coast in an open dinghy, then took a tubby schooner through the Furneaux archipelago, south of today's Victoria, and around Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), thereby plotting a shortcut for shipping through the Bass Strait that would save His Majesty's fleet a month at sea.

Impressed, Admiralty top brass handed him the command of a two-year scientific expedition in 1801. Flinders became not only the first person to circumnavigate and chart Australia, he pioneered the continent's name. Like Asia, Africa and America, Australia was "more agreeable to the ear" than the contemporary Terra Australis, he wrote.

As the man who put Australia on the map, Flinders is a national figure down under. A town and mountain range plus numerous institutions and streets bear his name. But nowhere embodies his intrepid spirit like Flinders Island off the north-east Tasmanian coast.

Flights now shuttle to the island daily from Melbourne or Launceston in north Tasmania. But toothpaste-tube prop planes and the chance of a storm helter-skeltering across the Roaring Forties foster a vague sense of derring-do about any visit, and for most tourists to Australia, Flinders Island remains as remote as when it was charted by Flinders himself in 1798. I was only the sixth Briton to arrive in a year.

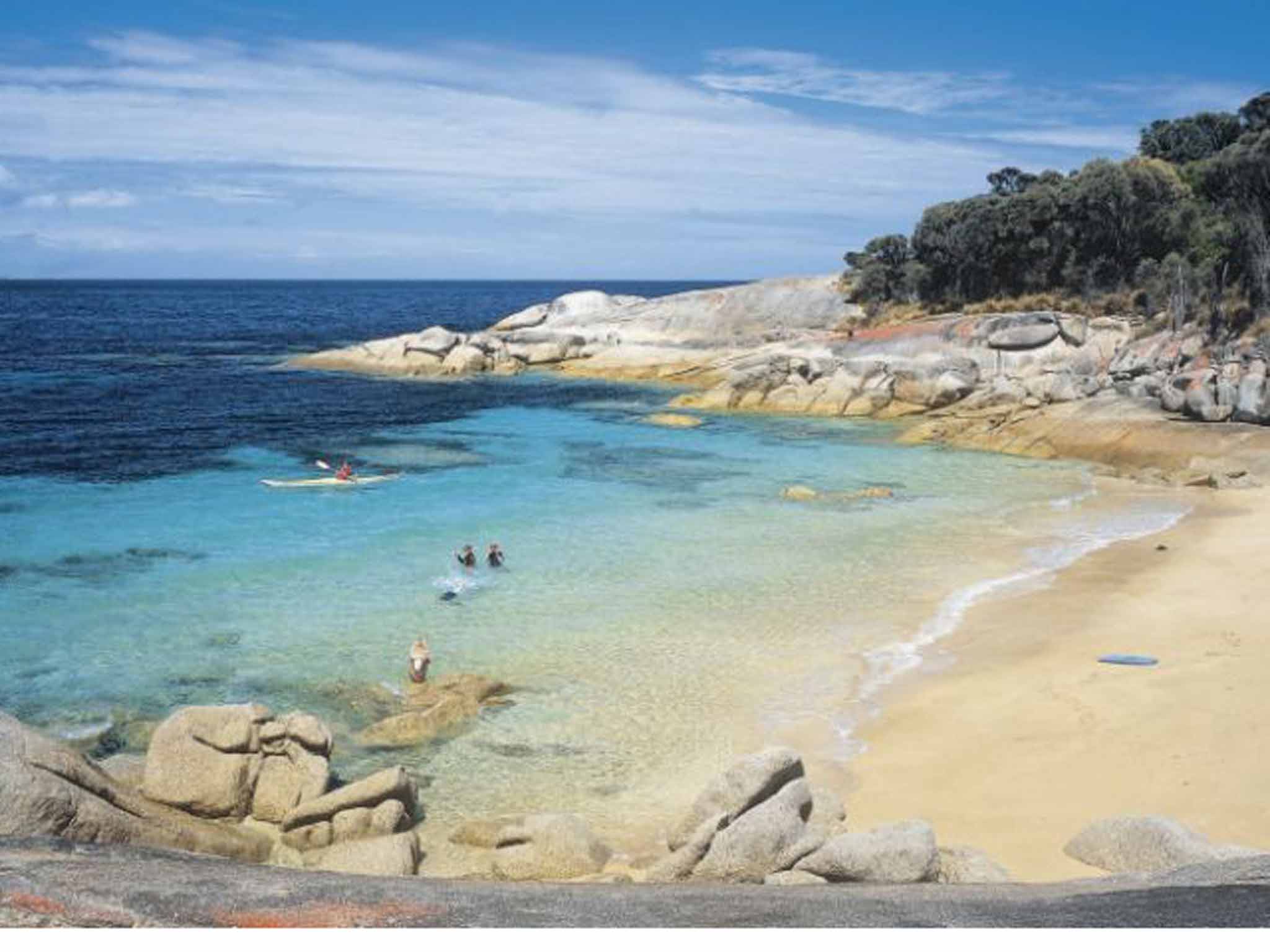

It's small wonder that in-the-know Australians rave about the place. The Sydney Morning Herald recently included the entire 60x40km island on its list of Australia's five best secret beaches (it was impossible to decide on just one, it said). Divers report historic wrecks off the east coast and 10kg crayfish for the barbecue, while bushwalkers compare Flinders to famous bits of north-east Tasmania such as Freycinet National Park, or Wilson's Promontory National Park near Melbourne. Every- where you go are wallabies and wombats, like corpulent teddybears. It is, a park ranger told me simply, the last Eden in Tasmania.

What Flinders Island lacks is people. If there's someone on the beach, go to the next one, locals say. And on an island with more than 100 beaches for 700 residents they're only half-joking.

I could've lost a week simply exploring down dirt-tracks to one dazzling strip of sand and sea after another; from an epic 34km stretch that arced around the marshy east coast, to Mount Tanner on the west. It wasn't hard to see why Melbourne city dwellers increasingly look south for their beach retreats.

"People sometimes talk about Tasmania being in the 20th century," said Doreen Lovegrove. "Well, Flinders is back in the 19th." I met the octogenarian author of A Walking Guide to Flinders Island in the island heritage museum at Emita – a hoard of sepia charts, flotsam and aboriginal artifacts which sums up the island's early history. "We're definitely not for the high-rise tourist – everything happens a bit slower here and the isolation gets to some people. Both are reasons to come if you ask me."

The game-changer for the island's profile, she said, could be the Flinders Island Trail. The route will upgrade existing four-wheel-drive trails into a serpentine walking track between the island's tips. The tourist authority hopes its interlinked daywalks through coast, pasture, and mountain valleys will catapult the island into a premier-league walking destination when fully opened around 2016.

To sample a section, Doreen directed me towards The Dock near Killiecrankie on the north-west coast. I picked up the trail off the main road and walked for a couple of kilometres shaded by sheoak scrub. Then I stepped on to the beach and the world exploded into super-saturated colour. Granite bubbles the size of my rented accommodation at Emita were splashed by bright orange caloplaca lichen – evidence of the pure air of the Roaring Forties. In the luminous light the sea shimmered improbable shades of turquoise.

If I felt like I had stepped on to the set of an outré sci-fi; Lincolnshire-born Matthew Flinders must have thought himself on another planet.

"For 30 years after his visit, the island was left to the Straitsmen, a renegade band of sealers and whalers who took aboriginal wives. Then Van Diemen's Land governor George Arthur seized upon Flinders Island to resolve his "Black Wars" with the aborigines. Tricked into believing it a stopgap, the last 135 aborigines of Van Diemen's Land were resettled at Wybaleena in 1834.

A lonely vale on the west coast, Wybaleena – literally, "Black Man's Houses" – still feels haunted; more dreamscape than landscape when I visit in a fine drizzle that had misted a glade of sheoaks to ghosts. At their centre stood the boxy chapel in which the aborigines, forced into European dress, were preached hellfire and brimstone.

Is it any surprise only a third left the island? The rest succumbed to pneumonia and malnutrition. Probably despair, too, as months in a military prison, run with a missionary zeal to civilise and Christianise, dragged into years then a decade. Only 47 left the island in 1847 after they petitioned Queen Victoria. Within three decades all were dead.

Given the history, it is ironic that Flinders today is the wellspring of aboriginal culture in Tasmania. The direct descendants of Straitsmen and their aboriginal wives now practise the harvest of short-tailed shearwater chicks. Greasy duck marinated in fish oil is how one local described the taste, though that hasn't stopped one firm peddling it as a source of Omega 3.

Part bygone backwater, part Robinson Crusoe, with a pinch of Star Trek on the side, Flinders Island is a place where fantasy and reality blur. You could lose yourself for weeks out here, and not just because of iffy map-reading.

After breakfast on the terrace above Emita Beach (empty again), I explored south the next day. Mountain peaks filled the windscreen: cone-like citadels in the Darling range; Pillingers Peak, stepped like a ziggurat; and the granite massifs of the Strzelecki National Park in the island's south-east corner.

My goal was Trousers Point, within the national park, for one of Tasmania's most celebrated short walks. For a happy hour or so I ambled along the foreshore, gazing over empty seascapes to distant Furneaux islands with only albatross for company.

But it was the powder sands of Trousers Point Beach that kept me till dusk. As the sun dragged the sky sizzling into the sea, burnishing the Strzelecki peaks a pale gold, the azure shallows deepened to indigo. It was achingly, heart-stoppingly beautiful.

Matthew Flinders, who anchored offshore, probably witnessed the same scene, I realised. Then the beach vanished into the night, I returned to the car and modernity returned once more.

Getting there

James Stewart travelled with Tasmanian specialist Tasmanian Odyssey (01534 735449; tasmanianodyssey.com). Discover the World (01737 214291; discover-the-world.co.uk) offers 12-day trips for £2,175pp, including return flights from London Heathrow to Melbourne and to Flinders Island, 10 nights’ accommodation at Partridge Farm on the island, plus two nights in Melbourne.

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments