Cornish Mexico: How the pasty was transported to the Sierras

The 19-century miners who brought the comforts of home to the Americas

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Aman walks down a street in Real del Monte, an old Mexican mining town. As he goes, he's munching on a Cornish pasty. Along the surrounding streets, shops offer the auténtico paste (pronounced pastey, not like sticky paste), a "delicacy of English gastronomy for Mexico", and they display the black-and-white St Piran flag of Cornwall. This is a place where the pasty, and other Cornish influences, are celebrated with devotion.

The centre of Cornish Mexico is the city of Pachuca, capital of Hidalgo State and its old silver-mining district, 95km north-east of Mexico City. However, its real heart is little Real del Monte on a mountain top above it (officially Mineral del Monte since Mexican independence, but virtually everyone still uses the old Spanish name of "Royal Town on a Mountain", or just El Real).

It's a classic Mexican mountain town of steep cobbled streets and houses in bright blues, pinks and yellows, in what to many would seem an un-Mexican setting; at more than 2,600 metres, Real is one of the highest towns in the country, and the weather can be as brisk, wet and chill as anywhere in Cornwall. To the north, narrow roads wind up into magnificent landscapes of dense pine and cedar forest, lakes, mountain crags, bizarre rock formations, colonial mining villages and old Spanish silver haciendas.

The Cornish presence in this remote spot goes back to the days when Cornwall was known (as Poldark reminded us) for copper and tin mines, and Cornishmen were famed as the most skilful hard-mineral miners in the world. They also suffered – again as per Poldark – from chronic insecurity. In Mexico, in the 1820s, the silver mines of Pachuca and Real were derelict and flooded after the bloody war for independence. The new government was keen to see them reopen, and in 1824 the main Hidalgo mines were sold to a group of London investors, the "Company of Gentlemen Adventurers in the Mines of Real del Monte", who immediately began recruiting miners and engineers in Cornwall.

The "great trek" of this first Cornish contingent was a combination of the epic and the absurd. Some 130 men, women and children sailed out in spring 1825, with the finest mining technology of the day – Cornish steam beam engines. They reached Veracruz in yellow fever season, which killed many within a few weeks. It took a year for the survivors to cover the 400km to Real del Monte, dragging their great iron engines by mule or rope through jungles and over mountains.

After 25 years, the Gentlemen Adventurers sold out to a Mexican company, which continued to rely on the Cornish to run its mines. For decades, Cornish miners were recruited through the same local and family networks. They also set up their own enterprises, none more so than Frank (or Don Francisco) Rule, the "Silver King" of Pachuca, who arrived in 1853, aged 17.

Specialising in rediscovering old abandoned mines, he became immensely rich, and left a permanent mark on Pachuca. The city's foremost landmark in the main square is its monumental clock tower, presented by the British community, with Rule as main contributor, for the centenary of Mexican independence in 1910, and with a chime that mimics Big Ben's. Alongside it is the Neoclassical former Rule Bank, while a few streets away is the grand mansion that he built for himself, the Casa Rule, now the City Hall.

After the Mexican Revolution exploded in 1910 many families drifted away, but others filtered into local society. Ricardo Ludlow, an economist and fifth-generation Cornish-Mexican, told me that Ludlows have spread into many areas of Mexican life: a prominent scientist, a film producer (José), another Ricardo Ludlow who was an extravagant 1960s bohemian revolutionary.

Typically Cornish mine engine-houses and their tall chimneys still stand out in the landscape around Pachuca and Real – two of them are now mine museums – but the community's greatest monument is the extraordinary English cemetery, the Panteón Inglés, on a hilltop above Real del Monte. The wistful Victorian graveyard is enclosed by a stone wall, shrouded in pines and lit up by views over the town below. The oldest gravestone dates from 1834, and around it are 750 more. Each could be the basis of a novel, like that of "Isaac Edward Richards, of Breage, Cornwall, England, who lost his life at Santa Gertrudis Mine, Dec 30th 1896, aged 26 years", or the memorial to Pachuca-born Private John Vial, who travelled back for the First World War and died on the Somme in 1916. There's also the recent grave of Don Chencho, Inocencio Hernández, an ex-miner who took care of the cemetery for 40 years and in return was awarded an OBE, which he often wore to work.

The Cornish brought other things to Mexico, such as Methodism and, most far-reaching of all, football. Pachuca is the "cradle of Mexican Football", with the oldest club in the country, and Mundo Fútbol, Mexico's lavish football museum. As with much of the Cornish heritage, there's a rivalry over ownership between Pachuca and Real. A plaque at the Dolores mine in Real del Monte states that the first-ever game of football in Mexico was played there in 1900, and there's a great old photo of a rough-and-tumble game outside the mine, but it seems the first proper matches were played at the Pachuca Athletic Club, another Cornish creation. Either way, Mexicans joined in, and the game very rapidly took off.

Locally, though, the most treasured legacy is the pasty. A string of paste shops, from holes-in-the-wall to glossy drive-throughs, lines the highway into Pachuca from Mexico City. In the rest of Mexico they're often called pastes de Pachuca. Again, though, it's Real del Monte that has a better claim to have seen the first Mexican pasties, and where there are paste shops on every street. Unable to live without proper pasties, the first miners even introduced turnips, previously unknown in Mexico. The process by which pasties took root is well recorded: Cornish wives taught pasty-making to their maids, who made them their own.

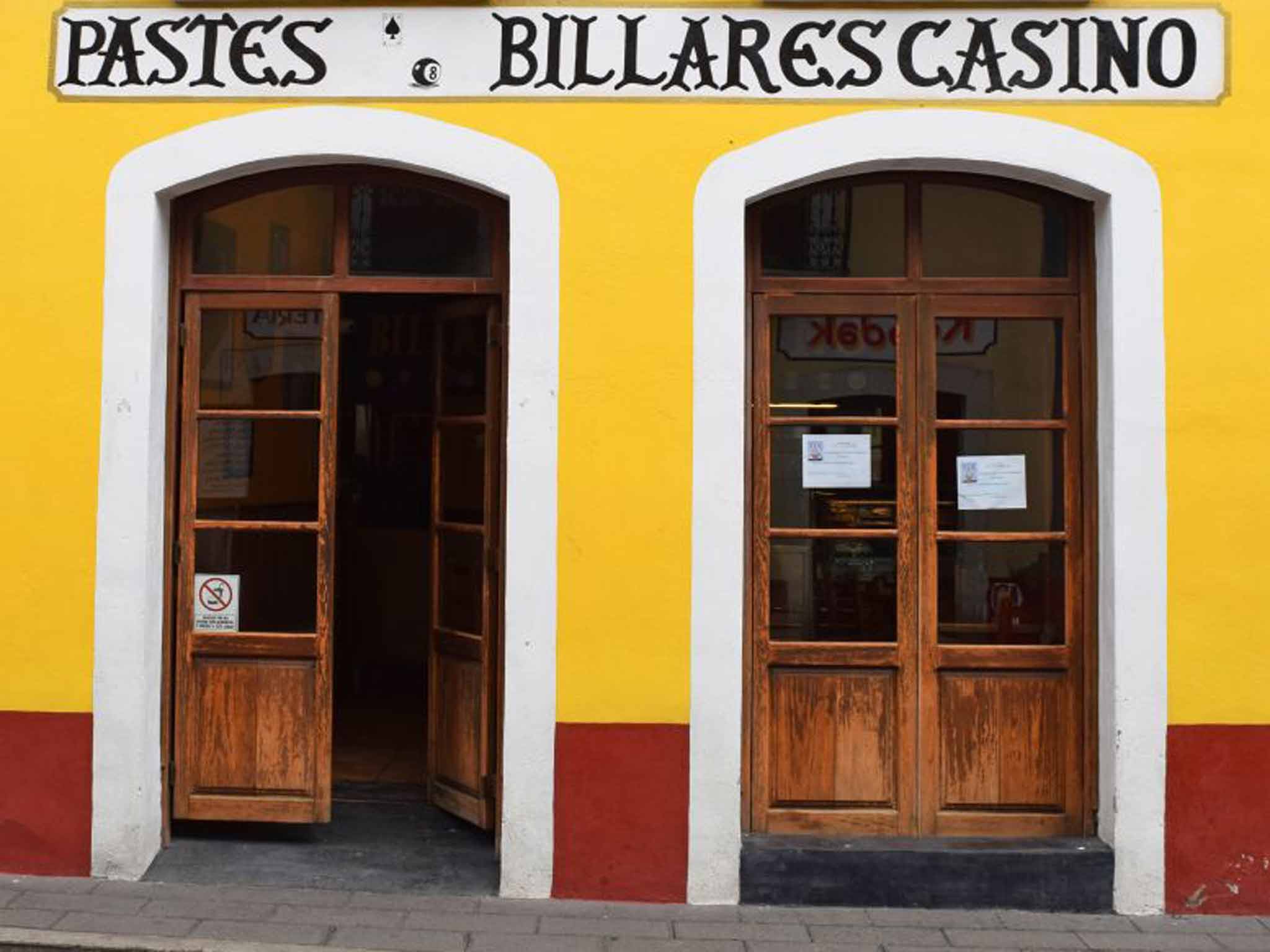

There was a gap between the dwindling of the Cornish community in the 1920s and the appearance of pasty shops decades later, paralleling the decline in the local mines. Don Ciro Peralta, whose Pastes El Portal on Real's main square – adorned with a fabulous mix of Cornish and Union flags, bright papel picado banners, Cornish harbour scenes and other accoutrements – is one of the town's best, still worked as a miner for years after beginning his family pasty business in 1975. Like Cornish miners he took home-made pastes with him down the mine, and he and his wife began selling them in schools as a way of getting out of mining. He treats pasties with great respect. "The history is very important," says Don Ciro, "we have to know how to value what the English left us."

Not that a paste is the same as an everyday pasty. It comes with many different fillings: red mole (savoury chocolate sauce), hotter green mole, refried beans, pineapple and tinga (shredded pork or chicken in chilli).

One popular flavour is zarzamora con queso (blackcurrant and cheese), and there are even fish pasties for Lent. Even a traditionalist like Ciro Peralta makes his "classic" meat, potato and turnip pasties with extra herbs and a dash of jalapeño.

Memories of these links between Hidalgo and Cornwall had been fading, so much so that many locals were convinced pastes were their own invention, but they have been revived since 2000, not least by the Cornish-Mexican Cultural Society, which inspired the twinning of Redruth and Real del Monte in 2008. In Hidalgo – where the last mine finally closed in 2005 – this has helped the paste become the district's new trademark.

Real del Monte now has the world's only pasty museum, the Museo del Paste, which tells the story of the Cornish and the pasty in Hidalgo in loving detail and lets you make your own pastes under expert supervision. Last year, it even had a visit from Prince Charles and the Duchess of Cornwall. Since 2009, the town has also held an International Pasty Festival each October, a three-day celebration of everything pasty that so impressed Cornish visitors (perhaps a little embarrassed they hadn't thought of it first) that they set up their own equivalent in Redruth. Like Real del Monte in general, the festival is a very friendly event. And you don't have to be Cornish to enjoy it. Though it may get you an extra pasty.

Getting there

British Airways (0344 493 0787; britishairways.com) and Aeromexico (0800 977 5533; aeromexico.com) fly non-stop from Heathrow to Mexico City. From the capital, ADO buses (ado.com.mx) run to Pachuca every 10 minutes, taking 90 minutes for a fare of M$98 (£4).

Staying there

Villa Alpina – El Chalet, Real del Monte (00 52 771 797 0077; villaalpinaelchalet.com). Chalets from M$750 (£30).

Eating there

Restaurante Real del Monte (00 52 771 797 0996).

Visiting there

Mundo Fútbol, Pachuca de Soto (00 52 771 138 3040; mundofutbol.com). Admission M$135 (£5.20).

More Information

The Festival Internacional del Paste in Real del Monte takes place from 9-11 October (consejodelpaste.com).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments