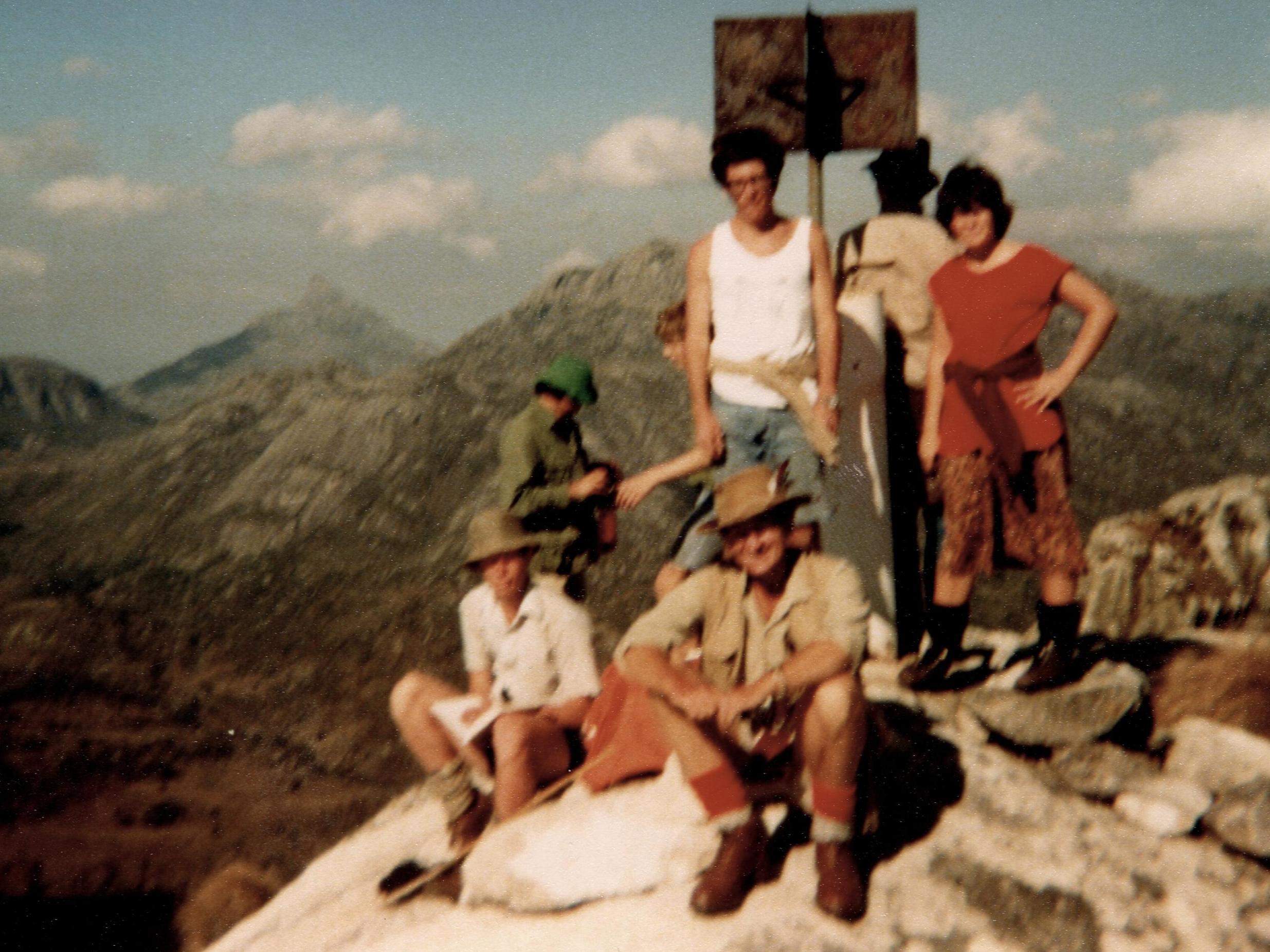

That Summer: Hiking Malawi’s Mount Mulanje in a skirt in 1979

Siobhan Mulholland, a self-conscious teenager, found a five-day hike exhilarating and memorable – ‘for reasons both universal and particular’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This piece, which was originally published as part of The Independent’s That Summer series, has been revised by the author. Find out more about it here.

Mount Mulanje, in southern Malawi, is a beast of a mountain: two metres over the 3,000m mark with one of the highest peaks in southern Africa. But from what I remember of my ascent in the summer of ’79, it is more of a strenuous hike than a climb.

I was a young teenager when my parents were living in Malawi’s capital, Lilongwe. That summer I had been released from a miserable English boarding school to enjoy a couple of months of expatriate privilege by swimming pools, Lake Malawi and, occasionally, visiting a game park.

My family’s exploration of a country tended to be relatively tame, with comfort being a priority. We were not hardy, we didn’t have kit such as sleeping bags or rucksacks and we never camped or stayed anywhere for long that didn’t have air conditioning. So when a couple of more robust families invited my brother and me to join an expedition up Mount Mulanje, at the time it sounded very alternative.

Our fellow climbers were British High Commission families: Mr and Ms Wilson and their four teenagers; and Ms Collins and her four, plus their German foreign exchange student. (Bit of a coup, that, getting an exchange to southern Africa rather than Surrey).

I don’t remember knowing the families well, I had probably bumped into their children on an end-of-term flight out to what was called “post”, or met them at the High Commission club during a holiday. There was no social media to ease the coming together of 10 pasty-faced British teenagers on an expedition up an African mountain.

The organisation by the other families was impressive. A travel itinerary and a list of what to pack was given to each person. Which clothes to take was the biggest challenge for me. In 1979, Malawi was a one party state under the dictatorial rule of “president-for-life” Dr Hastings Kamuzu Banda. He allowed no opposition or dissent; those who put their heads above the parapet were imprisoned or killed.

The draconian laws he imposed on his country, one of the poorest in the world, were repressive, harsh and bizarre. At the bizarre end of this totalitarian spectrum was Dr Banda’s big hang-up about 70s fashion. Men were not allowed to wear flared trousers or have long hair; it had to be cut above the collar. Women were not allowed to wear mini-skirts, shorts or trousers, only below-knee length dresses and skirts were permitted.

This posed a real problem on my first mountaineering expedition: how many people have you seen climbing mountains in below-the-knee A-line skirts? Banda’s dictates did nothing to help a self-conscious teenager’s agony over which T-shirt would go with which sartorially tragic skirt.

The only way to reach Mulanje from Lilongwe was by road, via the M1. Unlike its letter-and-numbersake in Britain, this was a badly pot-holed single lane, running from the north of the country to the south. What you didn’t want to do is what we did: get stuck behind a lorry for most of the way and have to sit in the back of a 1970s British Leyland Land Rover.

They don’t make them as uncomfortable as that anymore.

We stopped several times: to let cattle cross, change a tyre, look at wood carvings being sold at the roadside, and allow a couple of funeral processions to pass. Wherever we pulled over, even if there were no village or huts in sight, Malawian children would appear and wave. You couldn’t rush a trip like this; we were an amiable country with a slow pace of life and our drive reflected this.

My brother and I met the others at a tea-planters’ house at the base of the mountain, which is where we were introduced to our porters, who were friendly and keen to help. From here, we were taken to our starting point in the back of a lorry. What followed was a surprising and memorable five days.

Mulanje is a big mountain, covering an area of 600 sq km – bigger than the Isle of Man. It’s steep, rising dramatically from an undulating plain below. Malawians call their mountain “Island in the Sky” because its peaks soar up above the clouds. The highest peak is Sapitwa at 3,002 metres.

However, for beginners Mulanje is a treat of a mountain; you don’t need to be a rock climber to reach most summits and you can walk from one side to the other.

It took five days to cross the Mulanje Massif. Only day one was arduous: a four-hour ascent to the plateau. Any views to be had were covered in mist, drizzle dampened our spirits and clothes, and my feet hurt in my borrowed boots.

But once on the plateau, the weather cleared, the sun came out and from then on we had perfect hiking weather: cool, clear and sunny. We visited in the middle of Malawi’s dry season when the country’s climate is kind to hikers.

The elemental beauty of Mulanje has always stayed with me: deep valleys, gentle plateaus, waterfalls, rock pools and the extreme contrasts of barren rock and lush vegetation. The light is brighter and clearer that high up, far away from contamination.

I don’t remember there being much of a wind during our hike, more of a breeze and a very blue sky with occasional drifting clouds. The only hint that anyone had been there before us was the network of winding footpaths, there was no rubbish anywhere in this most pristine of landscapes.

Each day, we walked three to six hours to a different rest house. It was a gentle trek; the porters did the hard work. Our party tended to split in two, with the eager, competitive personalities striding ahead and those, who were less interested in winning, brought up the rear. If the distance between the two groups became too much Ms Wilson would yodel “coo-eee” across the mountain; an incongruous sound in such African isolation.

The rest houses we slept in were basic and clean; wooden huts with bunks, benches and open fires. In the evenings, Ms Wilson and Ms Collins took it in turns to organise a supper of stew or curry. This was followed by a tin cup of Malawi brandy.

Maybe it was the altitude, maybe the tiredness, maybe my inexperience at drinking brandy, but I found the Wilson’s German exchange student particularly interesting after one of these nightcaps.

Traversing Mulanje will always be a standout memory for me, for reasons both universal and particular: the panoramas are still surprising clear, the exhilaration of making it to the peak likewise stays with me – as do the feelings of awkwardness of travelling with people you don’t really know. That said, I knew then and I especially know now how special those few days were.

I’ve promised myself I will return to Malawi, and to Mount Mulanje.

It’s true that when I holidayed there, in the late 70s, it was arguably an easier time for the country; exports of tobacco and tea were doing well, the war in neighbouring Mozambique had not begun, and Aids was yet to decimate. But for the tourist, I’m told that Malawi is still a paradise to visit, and Mulanje a magical mountain to climb.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments