St Helena: Will a new airport spoil its wild and rugged charms?

The exiled Napoleon had no choice, but modern visitors come to this remote island because of its isolation. So, asks Tricia Hayne, will a new air link change all that?

When did you last hear the rumble of a jet overhead? Or idly watch as its vapour trail dissipated into so many fluffy cloudlets? For most of us such things are of no more interest than a passing car, but for the Saints – the islanders of St Helena – they would be strange indeed, for in their aircraft-free world, the sea still reigns supreme. Not for them the hassle of airport security: their link with the outside is the Royal Mail Ship St Helena, which fetches and carries letters, groceries, family members, cars, tourists, roof tiles – indeed, everyone, and almost everything.

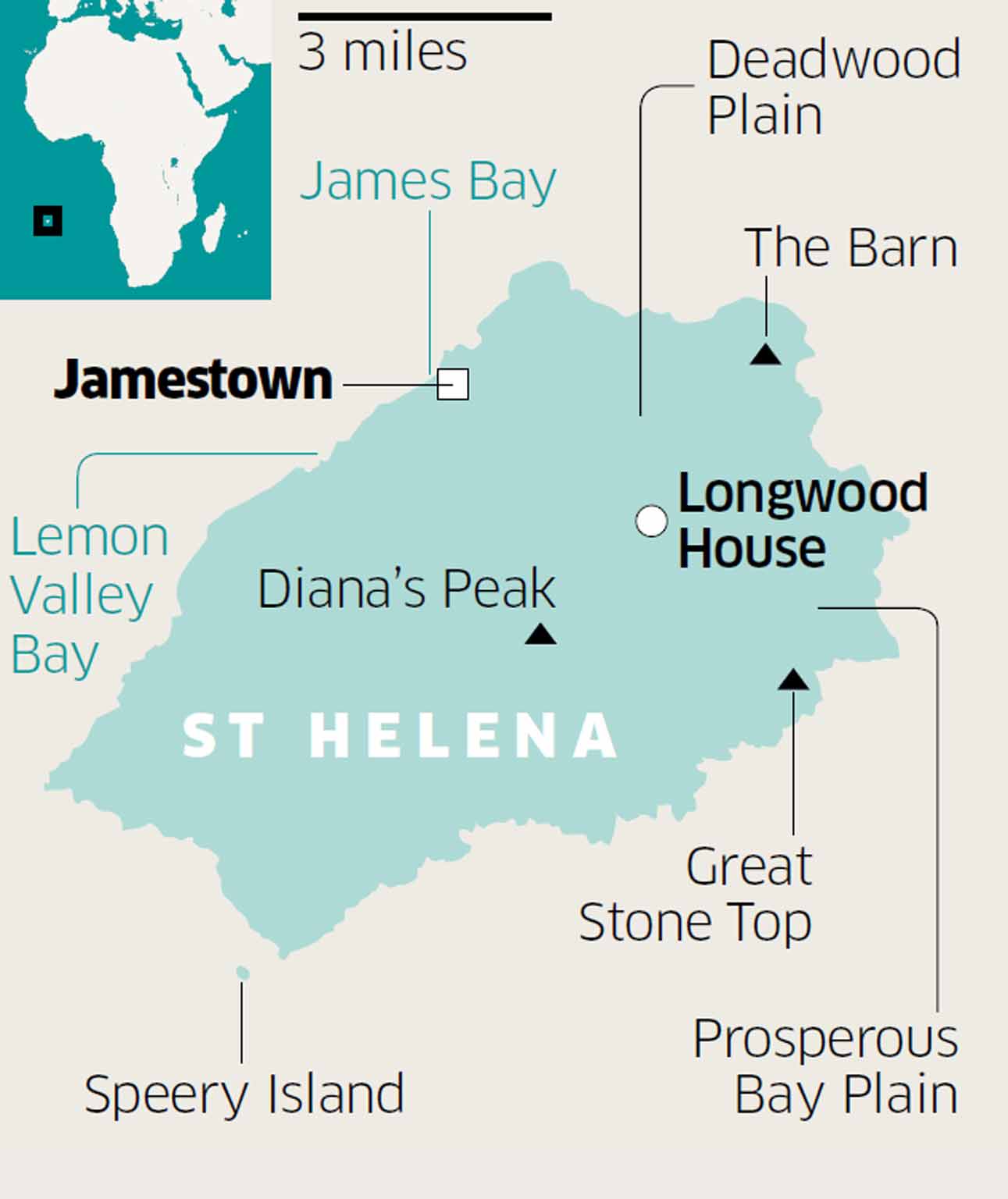

Yet all this is set to change. In 2016, more than 500 years of maritime history will come to an abrupt halt when the first commercial aircraft lands on Prosperous Bay Plain. At one snip of the ceremonial ribbon, could this remote island find itself moved up the ranks of the traveller's bucket list? Or will an airport detract from its appeal?

But first things first: where on earth is St Helena? A fair few people can link the island with Napoleon's final exile, but ask for anything more specific and you're likely to get a vague, "in the Mediterranean?". Google plumps for the Napa Valley in California. But Google would. And both are thousands of miles out. When the British government was faced with what to do with Napoleon after Waterloo, St Helena – deep in the South Atlantic – was the most inaccessible and impregnable place that it could come up with. In the 200 years since, not much has changed.

Effectively the tip of a volcanic rock, St Helena is scarcely bigger than Jersey. The nearest land of any description is the even smaller Ascension Island, but to get somewhere more substantial, you're looking at 1,200 miles of unbroken sea. And that only brings you to the wilds of southern Angola. In the days of sail, James Bay was busy with ships taking advantage of the south-east tradewinds. Now it's the big cruise ships that call, along with a handful of hardy trans-Atlantic yachtsmen, and – last year – just 736 curious visitors, courtesy of the RMS St Helena. Their reasons for coming vary. Napoleon, megalomaniac that he was, would no doubt have claimed that it was his influence; after all, he endured five whole years on this "cursed rock", and he has certainly put the island on the map. Most, though, are enticed by the very reasons that brought him here – the isolation, the remoteness, the sheer inaccessibility.

It takes six days to make the sea crossing from Cape Town, a leisurely voyage that's akin to St Helena itself: friendly, relaxed, and with excellent food – and a very competitive line in deck cricket against the predominantly St Helenian crew.

As the ship draws near in the early-morning light, we muster on deck for a first glimpse of the island. Through the mist, a jumble of tiny houses materialises at the foot of dauntingly dark cliffs, their scale all wrong, as if a child had scattered them in error. Jamestown, from the sea, looks more Toytown than cosmopolitan capital.

We've plenty of time to take it in while the ship drops anchor and preparations are made for our transfer to the wharf. Once we're ashore, immigration officers in the smart new customs house welcome us to St Helena. Genuinely welcome us; this is no learned behaviour. Beside the old moat, we stop in a busy open-air coffee shop, where a couple of St Helenian women join us. Within moments, we're talking; of the island, of our plans, of their jobs. Through the town gate, cars stand guard on the Grand Parade where once soldiers stood to attention. Then Toytown morphs into a film set: a wide street lined by beautifully preserved Georgian houses. You can almost picture the doors opening for 18th-century ladies in their finery. But there's nothing romantic about the town's military history (they were a mutinous lot, those soldiers), nor about Jacob's Ladder – all 699 steps of it – which was installed to haul manure up the cliff side. The only way out of Jamestown is up, and the ladder is the toughest option, but the roads – one heading west, the other east – aren't much better. Narrow, single track and very steep, they come with passing places that are often obscured by solid outcrops of rock. This is no place for the nervous driver.

Barely six miles from Jamestown, Napoleon's home in exile was a barren wasteland. The mere sight of The Barn, a forbidding lump of volcanic rock that looms over the island's north-east, made him deeply depressed. No wonder. The man craved challenge and power, not scenic grandeur. Imagining Longwood House as it once was, damp dripping down the wallpaper, floorboards rotten underfoot, it's hard not to sympathise with him. Today, though, it's an altogether more jaunty picture. The French tricolore flies over gardens that were designed by Napoleon himself. Inside, you'll find the copper bath where he read and conversed with his entourage; the dining-room table where he insisted on formal dinners every evening; the bed where he died.

Or at least you will, come the end of 2016 because these treasures are currently on loan to Les Invalides in Paris. But there's poignancy in the billiard table that was scarcely touched; the maps that hark back to campaigns long laid to rest; the peepholes cut into shutters so Napoleon could spy on the sentries who patrolled the grounds.

For us, who have the freedom to explore, the whole drama of St Helena's landscape unfurls beneath our feet. From the top of Diana's Peak, densely greened with species of vegetation found nowhere else on Earth, we look down on rolling hills etched with deep "guts"; on neat triangular peaks reminiscent of textbook volcanoes; on mile upon nautical mile of sea stretching to the horizon and far beyond. We scan Deadwood Plain for the endemic wirebird, and are rewarded with fluffy chicks, motionless and vulnerable in the rough grass. We tackle challenging Post Box walks, walking through millions of years of geology to absorb the views, and swim in natural sea ponds overlooked by the solitary pillar that is Lot's Wife.

From the deck of a tourist boat, the Enchanted Isle, those formidable cliffs come closer, bristling with fortifications that speak of years of military rule, while lower down, roughly knotted ropes testify to the dangers faced by fishermen seeking to put food on the family table. Up close to Speery Island, black and brown noddies peer at us from their seabird hotel. And out at sea, pan-tropical spotted dolphins do their thing, spiralling into the air and landing, like kids larking around, with an inelegant smack.

We paddle kayaks to Lemon Valley Bay, squadrons of fish leaping ahead of our bows while, high above, pairs of fairy terns compete in displays of synchronised flying. The lemons are long since gone, and there's no beach, but at weekends, the crude wooden deck and rusting barbecue pits are a great attraction for local families. As we slip into the water with masks and snorkels, the sea clear and warm, we're enveloped in a gold-and-white cloud of cunningfish – cute little butterflyfish that have evolved to live only here. Back on the rocks, waves of panic sweep through colonies of crabs at our approach, sending them scuttling into crevices shiny with algae. Later, we don wetsuits and scuba gear and nose around the ledges offshore, squeezing through improbably tight swim-throughs beneath roofs encrusted with cup coral, shimmering yellow in the reflected sunlight. And all the time, like a silver lure, dangles the tantalising prospect of seeing a whale shark.

When the moment comes, it is entirely unexpected. We're out fishing, dizzy with the excitement of catching wahoo and dorado, enjoying a day on the water. "I can't believe your luck!" calls local fisherman, Keith, from the cockpit. He's pointing to a dark fin, a few hundred yards from the boat, and it's heading our way. Breathless, we watch as 26 feet of dappled silver whale shark breaks the surface, wrapping its body around the stern as we slip into the sea beside it. Fully dressed, with no mask or snorkel, I'm woefully unprepared, but no matter. To swim, however fleetingly, alongside one of the marine world's least understood creatures is, quite simply, a privilege.

GETTING THERE

Voyages Jules Verne (020 7616 1000; vjv.com) offers a 24-night holiday to St Helena priced from £5,195pp (based on two sharing) including return flights from London to Cape Town, all taxes and transfers, 22 nights' hotel and cruise accommodation, including three nights in Cape Town pre-tour and one post-tour, breakfast daily, full board on RMS St Helena, three packed lunches and one dinner in St Helena, and guided activities.

When the passengers disembark from the inaugural flight to St Helena next year, their first experience of St Helenian hospitality won't be the ship; their first sight of land won't be Jamestown. They'll have spent a couple of days getting here, rather than a week; they'll taxi down the runway against a backdrop of volcanic scenery that culminates in the vertiginous Great Stone Top. But once they reach Jamestown, and set out to explore the island, the welcome will be there, along with St Helena's history, her dramatic landscape, her unique wildlife and, with luck, the whale sharks. It will take more than one plane a week to change an island that has evolved over countless millennia. So, my money's on it moving up travel's bucket list.

Tricia Hayne spent three weeks on St Helena updating St Helena, Ascension, Tristan da Cunha: The Bradt Trael Guide, for publication next month

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks