Rwanda's mountain gorillas: meeting the creatures saved from extinction

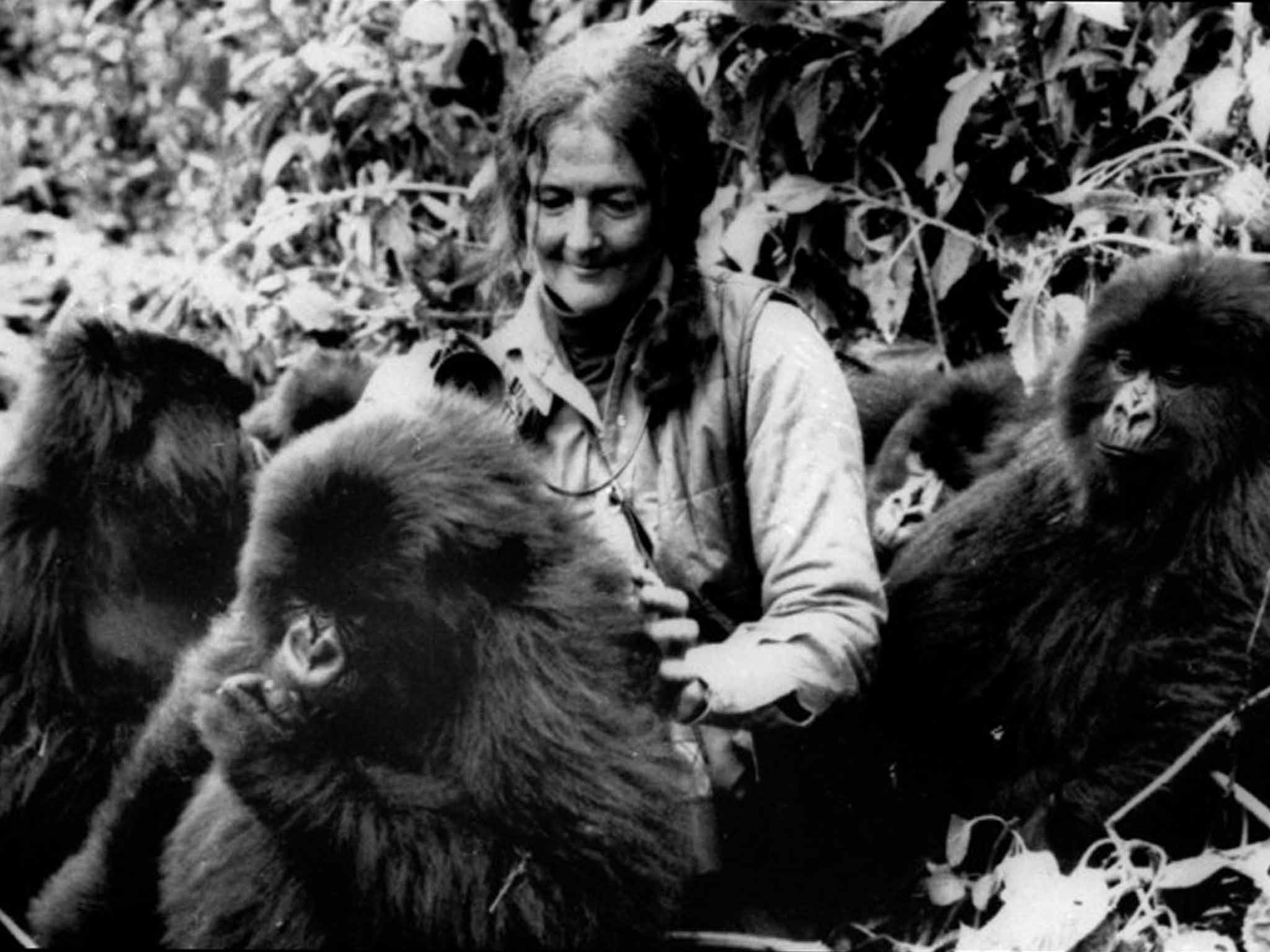

The mountain gorillas of East Africa were made famous by Dian Fossey who was killed here 30 years ago, and they continue to thrive

Dressed from head to toe in camouflage, with an assault rifle slung over his shoulder, the young soldier cuts an imposing figure as he emerges from the jungle. Two of his comrades follow him, offering reassuring smiles.

Like wellies and waterproofs, you really do need armed guards if you're planning on trekking in Rwanda's Volcanoes National Park. It might look harmless enough, but this vertiginous jungle is a place with nettles spiky enough to sting elephants, bogs that can suck in a grown man's legs and, most dangerously of all, highly aggressive buffalo, which can greet unwelcome visitors with a customary head-butt.

It's also home to man's closest living relative, the mountain gorilla, a critically endangered primate that shares 98 per cent of its DNA with us. Volcanoes National Park is the jewel in Rwanda's crown precisely because of these creatures, whose portraits adorn the country's bank notes, festoon its airport lounges, and appear on packets of tea and coffee, the principal exports.

Tracking gorillas here is an experience that tops bucket lists, but before I snap up one of the 80 permits allocated daily to see these primates, I have decided to follow in the footsteps of the woman who helped save them from extinction. This year marks the 30th anniversary of the death of Dian Fossey, an American zoologist who came here to study gorillas in the Sixties, and ended up staying until her murder almost two decades later.

"This is a pilgrimage," explains my guide, Francis Bayingana. "People walk this trail because they want to pay tribute to Dian Fossey's work and feel like they are part of it."

A trained occupational therapist from San Francisco, Fossey left the US in 1963 to travel around East Africa. She blew her life savings in the process, but she had found her calling. In 1966, she moved to Congo to study the gorillas. But political unrest pushed her across the border and into Rwanda in 1967, where she built a house and a ramshackle research centre. Everyone thought she was, well, a little crazy. "Local people called her Nyiramacibiri, which means 'woman who lives alone on the mountain'," says Francis.

The route we're following today is the one that Fossey took twice a month to fetch supplies from Kinigi, the nearest village. It's an arduous stomp and, as we climb the verdant foothills of Mount Karisimbi, the air becomes thinner and the mud thicker. Huge raindrops start falling from heavy clouds. I keep my head down, counting the seconds between flashes of lightning and rumbles of thunder.

By the time we reach a clearing the storm has fizzled out. "The question is," Francis says, with a performer's pause, "who killed Dian Fossey and why?" It's a poignant question given that we're standing on the spot where she was murdered on Boxing Day 1985.

Back then, this mossy ground was occupied by her house (which, weirdly, she christened The Mausoleum), but all that remains today are crumbling foundations and unsolved mysteries – still nobody has been charged with her murder.

Francis leads me through the undergrowth to Fossey's grave. "She wanted to be buried here," he says. "Next to her favourite gorilla, Digit."

Fossey's campaign against poaching and other gorilla-endangering activities, such as forest clearing, earned her many enemies, although even fellow conservationists struggled with her gruff personality.

"Some people think she was killed by poachers," says Francis. "But by the time she was murdered poaching wasn't really a problem." Other suspects range from gorilla-snatching zookeepers to fellow researchers, jealous of her success.

One thing we do know is that Fossey's legacy lives on. The 18 years she spent here, studying gorillas, inspired the government and locals to get behind conservation.

"At first, people didn't like her – they thought she was denying them their rights to hunt and graze cattle in the forest," says Francis. "But over time she started employing people – porters, trackers, researchers – and they could see her methodology and started to like her."

Rather than stymying her conservation work, Fossey's murder marked a new era for gorilla protection. The small charity she set up to tackle poaching, the Digit Fund, blossomed into the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International. Today it employs 120 people in nearby Musanze and has widened its conservation remit to include other species living in the park.

Hollywood played its part too, with the 1988 blockbuster movie Gorillas in The Mist. Named after Fossey's autobiography, it starred Sigourney Weaver and was nominated for five Oscars. "At the beginning there was just one voice," says Francis. "Then there were many."

After the hike, my legs are jelly, but the following morning I'm back in the forest with Francois Bigirimana, who worked as a porter for Fossey in the Seventies. He was with her when he saw his first gorilla and the experience inspired him to become a guide. What was she like, I ask him? "I think she liked gorillas more than humans," he says, coyly. "But now the gorillas are increasing. Why? Because of Dian Fossey."

Francois is taking me to see a gorilla family called Hirwa, who are grazing on bamboo shoots nearby. "When they eat 20 bamboo shoots it's like one beer," laughs Francois. "When they eat 100 it's like whisky."

Francois is a showman, a sort of Rwandan Ace Ventura. During the trek he impersonates gorillas, grazes on various plants, and talks endlessly about the sexual habits of the primates. "Sometimes they have two or three wives for jiggy jiggy at a time," he says. "Oh my god."

There's also a serious side to him. He talks passionately about the Rwandan government's revenue-sharing scheme, which distributes five per cent of the income raised through national parks to communities living near them. "In other countries tourists pay and the money goes into [the government's] pockets, but here it goes to the community," he says. "It helps build schools, hospitals and roads."

Eventually, we locate the gorillas, some of which are indeed the worse for wear from bamboo. We crouch quietly in the bushes and observe them grooming each other, play fighting, and snoozing. There are 19 in total, including one giant silverback, who looks like he's passed out, and two adorable twins, who crawl around chewing everything they see. The juveniles strut around, beating their chests and goading each other into fights. I feel privileged also to witness the tenderness shown by a mother to her baby, and laugh out loud when an inebriated blackback tumbles out of a tree. "He's so drunk," sniggers Francois.

I could watch them all day, but my hour, the fastest I have lived, is soon up. Francois signals for us to leave and I walk away reluctantly, gazing over my shoulder until they disappear from view, until they are gorillas in the mist.

Getting there

Gavin Haines travelled with Tribes Travel (01473 890499; tribes.co.uk), which can organise bespoke trips to Rwanda and neighbouring Uganda. Tribes offers an eight-day Rwanda tour for £3,990pp, taking in Kigali, Lake Kivu, the Nyungwe Forest, and the gorillas at Volcanoes National Park. Flights from Heathrow with Ethiopian Airlines (via Addis Ababa) can be added for around £650.

Staying there

Mountain Gorilla View Lodge (00 250 788 305 708; 3bhotels.com). Doubles from US$250 (£167), half board.

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks