Levison Wood's Walking the Nile: the challenge of a lifetime

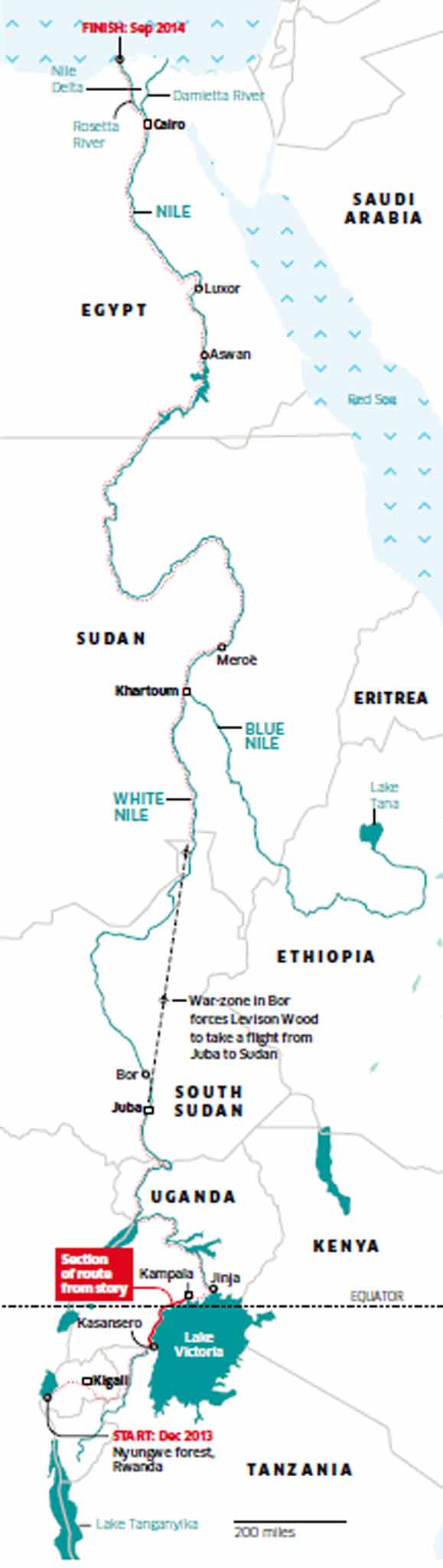

Last year, the explorer walked along the Nile from Rwanda to Egypt. It was a journey that took him through six African nations covering almost 4,000 miles in nine months. In this extract from his new book, Levison Wood describes the route from one of the river's sources, Lake Victoria, to the Ugandan capital, Kampala

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.North of Kasansero, the plan was to follow the shore of Lake Victoria for another 160km; seven days of hard trekking that would finally take us to Kampala, Uganda's boomtown and capital city.

In Kasansero the fishermen warned us that the way north was a morass of tributaries and dense swamps, and if we wanted to stay close to the lake the trek was going to be laborious. Boston, my guide, and I bickered about which route to take and, in the end, settled on a compromise: we would gather the services of a few locals and their boat – not to ride in, but to ferry our packs along the shore while we walked along the bank so as to make us light enough to move through the swamps, and if necessary swim around the mangroves.

There was something quite indulgent about walking along a beach for days on end, with palm-fringed shores, rickety fishing boats, and quaint wooden villages making it feel as if we were in a clichéd image of holiday perfection. Despite warnings of "chiggers", the voracious red mites that lived in the sand, it was too beautiful to wear boots and a nice change to walk either barefoot or in sandals, with the lapping waves to cool our feet. Most of the lake was flanked by thick forests, some of it national parkland, where colobus monkeys and waterbuck abounded. All along the shorelines, birds of every variety gathered in their thousands: sacred ibis, white storks, Ugandan crested cranes, and Egyptian geese.

Yet, for all this perfection, for long stretches paradise turned to hell. The locals in Kasansero had not been exaggerating when they called this place a quagmire. For miles the path disappeared into impenetrable mangrove swamps, and Boston and I hacked our way on, turning in circles, until we stumbled upon a trail blazed by locals to the next settlement along the shore.

More than once, I stumbled and became entirely submerged, having to be fished out of the stinking brine by Boston. We had backtracked in search of Boston's lost shoe, and spent 10 minutes working out a way to pull him out of the soft earth that was trying to swallow him up. There was a part of me – some insane, masochistic part – that was beginning to enjoy the torment, when Boston's eyes drew mine down to what appeared to be a pool of black liquid right beside my feet.

"It's a snake," he whispered. "Look, Lev! A python ...."

I saw the blackness uncurl and disappear, setting the surface of the water to ripples. I froze. Then, putting on my most nonchalant face, I smiled back at the overjoyed Boston. "It's probably just a mon- itor lizard."

"I don't think so, Lev." Boston had crouched and was already plucking a ghostly white snake skin from the reeds – by its rubbery texture, quite fresh.

An hour later, soaked to the skin, we stepped up on to dry land and, in front of us, stood three wooden huts and a crowd of villagers. By the remoteness of the place and the piles of shells lying on the sand it seemed they were shell-fish miners; men who collected shells to grind up and sell as chicken feed in the local markets. It is one of the worst-paid professions on the shores of Lake Victoria and, as they turned to see us, they were evidently thrilled. To them, strangers meant opportunity.

They rushed to meet us, eager to shake hands. One man cried out to congratulate us on not being constrained by such foolish things as "paths" – and, as the crowd shifted, I saw something staked out on the beach, reflecting the cruel midday sun. Boston and I shared a look. It was another python skin – but this one was more than six metres long and not a skin that had been shed. This gleamed black and blue, a true snakeskin taken from a dead python and pegged out to dry.

"You want to buy it?" a man asked. "I don't think I'd get it through customs," I replied, but the joke was lost.

Over the next days the shore alternated between dense swamp and pristine beaches where more landing sites like Kasansero had grown up. At times the mangrove forests were so alive with fire ants and spiders that we were forced to wade out into the lake and skip around the swamp instead.

From the moment we'd set foot in Uganda the local attitude towards us seemed to change; the villages we passed through were not as immediately suspicious as they had been in Tanzania, and the police didn't seem as eager to apprehend us for being spies. Uganda emerged from British rule in 1962 and it felt as if, unlike in some other corners of Africa, the colonial times were looked back on fondly. English is still the first language, though the languages of the different tribes also proliferate, and perhaps it was this shared tongue that made it seem an easier, simpler country to navigate.

On 23 January, the 45th day of our journey, came the first truly seminal moment in our expedition: Boston and I each took a single step and crossed from the southern to the northern hemisphere. We were straddling the equator.

Fifteen kilometres south of the small town of Buwama, two days' trek from the suburbs of Kampala, there lies a nondescript, diagonal line in the road. At each end of the line stands a clear circular monument, with the word EQUATOR etched into the concrete.

As Boston and I trudged up the Kampala road, the lake's shimmering vastness somewhere off to our right, we could tell we were near. Tourists had gathered around the monuments and there was a shop too, selling wooden shields and tacky key rings.

As we reached the line, I checked my GPS. According to the little contraption, the line itself was nine metres away from the actual equator, but, looking into the eyes of the gathered crowd, I thought it prudent not to mention this. In the south, Boston and I took one look at each other and, the next step, we were in the north. There was an element of theatrics in it but, as I beamed at the crowd – "At last," I grinned, "back in the north!"

At a coffee shop up the road we sat down to fortify ourselves for the 15km we meant to complete that day, and watched the tourists mill. It felt strange to be in the presence of other outsiders. Until now, I'd seen fewer than a handful of white faces in weeks – I'd been living, eating, and breathing an unseen Africa, one far away from the safari hordes and luxury lodges. The key rings being hawked from the side of the road cheapened the experience, somehow, but they also brought us down to Earth.

On the 47th day of our journey, Kampala came in sight. We were up before dawn, walking through the pitch black, past lay-bys where lorries were emblazoned with banners declaring "God is Great, God Is Good, God Is Everywhere!" and along a road where the traffic police kept demanding to know what we were doing.

In the hills outside the city, the country suddenly burst open with activity and life. The dirt tracks became roads, the roads sprouted pavements, and boda-bodas – the bicycle and motorcycle taxis peculiar to this part of Africa – appeared everywhere.

Walking into Kampala was like landing on the Moon compared with my experience of Uganda so far. It is wrong of me to say it felt like stepping from the past back into the present, but that was what came to mind as we saw the first of the city's skyscrapers in the distance and felt the crowds thickening around us.

Boston had described the place with such passion that I might have expected the streets to be paved in gold; but right then I would have given all the gold in the world for the promise of a comfortable hotel bed.

This is an edited extract from Walking The Nile by Levison Wood (Simon & Schuster, £18.99). His documentary series of the same name continues on Channel 4.

Read our 'My Life in Travel' interview with Levison Wood here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments