‘It’s always been counter cultural’: Is witchcraft part of an anti-science renaissance?

You can be a scientist and a witch at the same time, although not everyone is convinced that the two are easy bedfellows, writes Naomi Curston. With witchcraft on the rise, that could be a problem

Witchcraft “is not based on dogma or a set of beliefs, nor on scriptures or a sacred book revealed by a great man. Witchcraft takes its teachings from nature, and reads inspiration in the movements of the sun, moon, and stars, the flight of birds, the slow growth of trees, and the cycles of the seasons.”

This is how Starhawk, an author, activist and witch, defined witchcraft in her book The Spiral Dance in 1979. In other words, it’s a broad and flexible nature-based practice, and those who practice witchcraft may both use and honour nature in their spiritual practice.

As you read this, many witches may be gearing up for the new moon (the new moon is a great time to set intentions, as they will grow alongside the waxing moon over the next two weeks), but the way each witch marks this moon phase will be very different. Likewise, different witches have different ways of interpreting the world.

Some witches may worship a god and goddess; others may work with many deities. Some may place their faith in capital-S Spirit, or the universe, or something else entirely. Some may not have any conviction in the existence of a higher power, and see what they do as metaphorical.

People often think of Wicca and witchcraft as synonymous, but you can pair any religion with witchcraft: Wicca, Judaism, Catholicism… even atheism.

You can also be a scientist and a witch at the same time, although not everyone is convinced that the two are easy bedfellows. And that could be a problem since in the UK and US witchcraft seems to be on the rise.

There are certainly enough podcasts and books about it everywhere, and big articles in The New York Times, Glamour andThe Guardian.

Plus, official UK census data confirms the upward trend: the number of pagans in England and Wales between 2001 and 2011 went up from 40,000 to 57,000 (witchcraft is a type of paganism, although in the 2011 census 1,300 people identified separately as witches and 12,000 as Wiccan).

In 2017, Maia Miller, district manager of the Pagan Federation of Devon and Cornwall, told the BBC that the organisation thinks there might be over a million pagans in the UK. Today, Melissa Harrington, 56, deputy district manager for the northwest, is a bit more cautious.

“It’s always been counter cultural,” she says. “You’ve always had esotericism.” She is hesitant, however, to say that witchcraft is definitely increasing. “People have only just felt able to come out. They have been persecuted and lost their jobs so it’s really difficult to say. I would say it’s more accepted as a religious group. It might just be that it’s a bit more visible.

“It used to be mainly in covens,” she adds, “but now you have these eclectic and solo witches and all that and more people can claim to be a witch. They might not be doing full on practice, but that’s the same as many Christians.”

One place you might find the slightly more casual witch is on social media. At the time of writing, the r/witchcraft community on Reddit had 194,689 members, #witchesofinstagram had 5.6 million posts, #witchtok (on TikTok) had 5.3 billion views, and many a Twitter bio now includes “witch” in the list of descriptors.

But as witches have become more visible, so too has a small wave of anti-science: encompassing anti-vaxxers, flat-Earthers and creationists, among others.

Some people are worried that they’re connected, or, at least, that the growing popularity of a non-scientific belief system like witchcraft (especially when other religions are generally shrinking) could be part of a bigger pattern where we opt to reject scientific methods.

“The recent zest for the mystic is part of a worrying backlash against the enlightenment values that have driven human progress,” wrote Ceri Radford, a journalist who after a week of experimenting with all things witchy was left unconvinced.

Given that the writer conducted a thoroughly unscientific evaluation of witchcraft in her article, the statement in its context is unfounded, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it shouldn’t be given proper consideration.

But whatever it is that influences your attitude to science, is it a problem if a segment of the population chooses the Bible or Beltane over biology?

Because, if witchcraft is anti-science, whether actively or indirectly, then it’s a problem. And if witchcraft hurts science, then surely it follows that we should be equally concerned about other religions.

As Radford implied, and as a 2016 study into the religiosity of scientists stated in its introduction: “The prevailing argument is that science and religion are in conflict because they represent different ways of understanding the world.”

In 2018, a different study found some evidence to suggest that they might have a point. It examined the relationship between religiosity, and attitudes towards and knowledge of science. It found that, in the US, more religious people were less likely to feel positively and know much about science.

To measure religiosity, the study asked people to rate their confidence in God’s existence, how often they attended religious services, how often they prayed, how religious they considered themselves to be and the strength of their religious affiliation.

Although witchcraft can be quite different to religions like Christianity, many witches might still score highly on these questions: to different degrees they may believe in a higher power, they may meet with covens or conduct large rituals with varying frequency, they may consider themselves very religious or spiritual, and they may connect very deeply with a religious affiliation like Wicca, or simply with the identity of the witch.

Jonathon McPhetres, 35, an assistant professor of psychology at Durham University, was one of the authors of the 2018 study. On those who valued religion over science, he says: “Science is probably the best way to learn and to make our world a better place. It gives us opportunities to change things that don’t work so well. And here we have a group of people [religious people] who are putting less weight into these matters.

“They don’t hate it,” he adds. “They would just prefer something else.”

He is quick to point out that religion isn’t the only factor that could influence someone’s attitude to science, and this is where the link between religion and disinterest in science – particularly a specific religion like witchcraft – begins to unravel quite quickly.

“If you look at politics and climate change you can find big divides,” he says.

In addition, when spirituality was taken into account, the link weakened. This is important, as witchcraft’s flexible outlook means many witches will not define themselves as religious at all.

But whatever it is that influences your attitude to science, is it a problem if a segment of the population chooses the Bible or Beltane over biology?

“Some things are really important and some things aren’t,” Jonathon said. “Evolution really forms the basis of all biology… which forms the basis of how we develop medicines and how we breed plants and animals. Any area to do with life science, you need to accept that.”

One person who has no problem juggling life science and religion is Claire Toffolo.

Toffolo has an altar in her front room. On it, she keeps druid representations (the Ogham alphabet, which she first saw in a dream in 2013), and a representation of the goddess Hecate, a Greek goddess and her patron.

“The first thing I do of a morning is put fresh water and wine on the altar and say a prayer of thanks, every morning, because I am eternally grateful to them,” Toffolo explains, referring both to Hecate and to the druids, who supported her through some of the darkest parts of her life.

As well as the offerings, Toffolo carries keyrings that represent her witchy side – honouring Hecate, the druids and indicating her Celtic birth signs. But among the mystical, there are other keyrings that betray a different side of her – her marine biologist side.

While Toffolo, 41, from Devon, is a witch and druid, she is also a scientist. She studied coastal marine biology at university, and since then has worked as a marine ranger, a bar manager (which she hated), in an organic chemistry lab and as a pollution officer and waste water scientist at two different water companies. Despite having to give it all up in 2016 due to chronic illness, she’s still a member of the Royal Society of Biology and Royal Society of Chemistry.

“I really felt like I was making a difference,” she says, of her time with Welsh Water. “I was promised a good career there, which I was like: suits me! I love all this so long as you let me do my science.”

She chose to give up her science with Welsh Water to look after her mum in 2011 (she would return to it, albeit elsewhere, later), moving from north Wales to Devon, and it brought her back to witchcraft, which she’d abandoned in university due to poor health. But science and magic aren’t separate for her. She discovered Ancient Egyptian magic at 14, and her interest in it flourished alongside her determination to become a marine biologist, which she’d settled on at 11.

Now, although migraines and chronic pain prevent her from holding down her scientist job, she’s retraining to help others who live with chronic and terminal illnesses, walking a tightrope between science and spirituality. She is already a qualified herbalist, clinical hypnotherapist and qualified holistic health practitioner, among other things, and is working on seven more diplomas simultaneously.

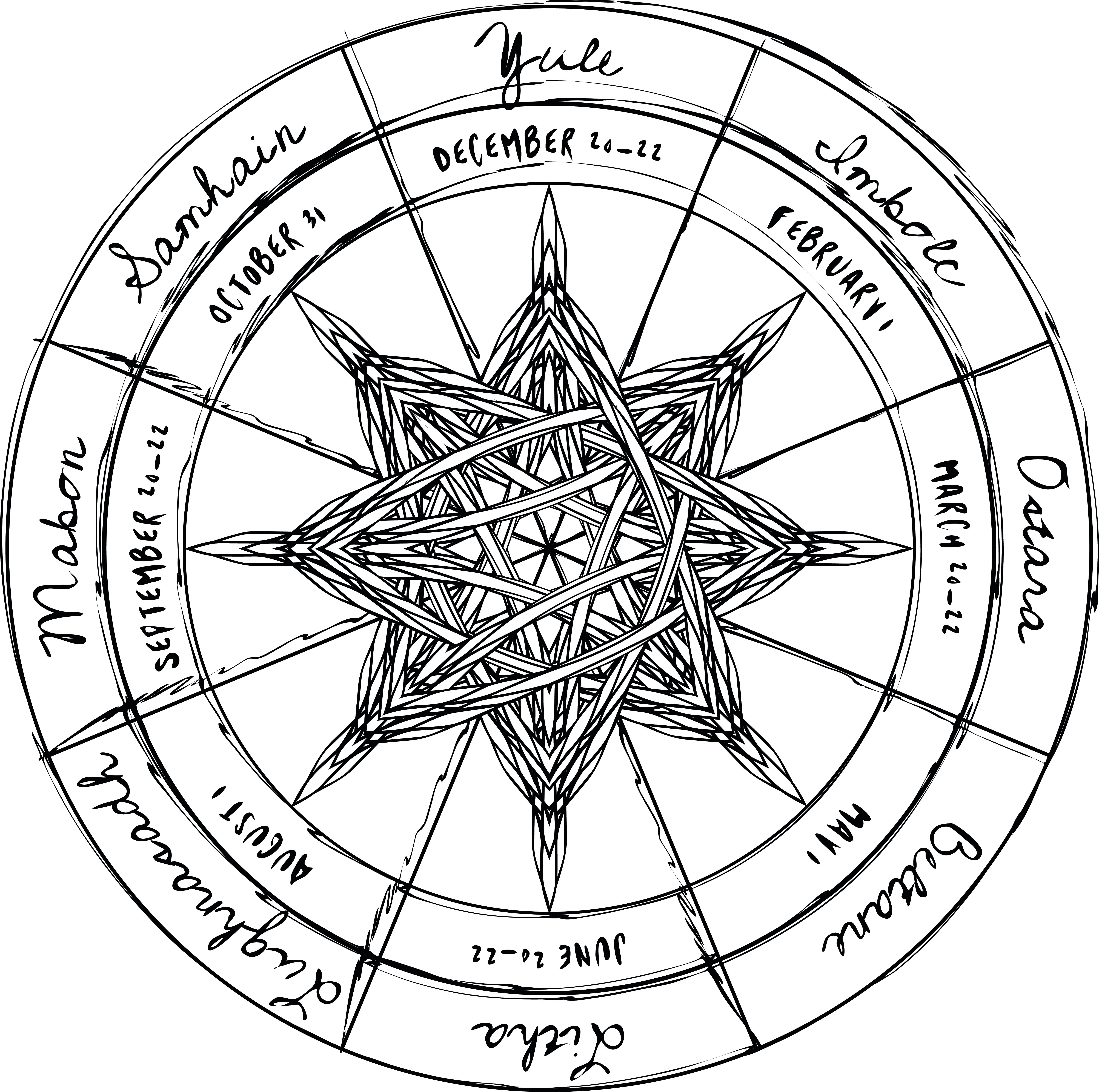

She walks this witchcraft-science divide a lot. A big part of any witch’s year is the Sabbats – eight festivals celebrating the changing seasons. Toffolo can’t always take part, but that doesn’t stop her from opening up her Book of Shadows and generously describing in great detail a previous Samhain celebration, right down to candle colour. You can see her scientific side leaking through – she is always precise, and even in this most spiritual book there are diagrams galore.

Kathleen Borealis (not her real name), 35, is another witch-scientist: a geologist and animist. She was born in the US but is currently based in southeast Asia. If you stepped into her workplace, you’d likely find her writing code (“What a lot of people don’t realise is that science now is a lot of computer science,” she says. “When you’re doing something new, no one else has necessarily written a program for you”) or fixing things for others – as she’s part of her university’s technical staff. But she also trains people and conducts her own research – anything from checking on geophysical instruments to taking observation photos.

When she has time to catch her breath – which isn’t often – she can also be found making her Borealis Meditation Podcast – a geology podcast that she started 10 years ago, planted firmly on the science-religion divide. It’s her science outreach project, and she wants to be the person people feel able to ask questions of.

Whatever you feel your relationship is with, whether it be a spirit or a deity or just your ancestors, you want it to feel like a friendship

She grew up in a non-religious household in the northwest US, but realised young that she was drawn to religion in a way that the rest of her family weren’t.

“I went to the library and I literally pulled an encyclopaedia of world religions off the shelf and started going through it like nope that’s not it, nope that’s not it,” she says.

She realised then that she was some kind of neo-pagan and now specifically identifies as an animist – where you believe that there’s something in everything but it’s not necessarily a god or gods. Her practice, meanwhile, is witchcraft.

That practice, in an everyday sense, consists of an altar, like Toffolo, which changes according to how she feels it should, and burning incense and oil. The incense is a nod to her current location, being a common practice in Asia, and isn’t something she did back in the US (“Being a geologist really gave a lot to my spiritual background because it really helped me connect with my environment around me,” she says). The oil is a thankfulness ritual or offering – she tries to hold onto uncertainty but if she does define “who” the offering is for, then it’s for local spirits, personal spirits or ancestors. She also has an ancestor altar, with pictures of loved ones.

“I try to balance it out so that my practice is based more on appreciation and saying thank you more than I ask for.

“Whatever you feel your relationship is with, whether it be a spirit or a deity or just your ancestors, you want it to feel like a friendship. You want to be the friend that gives more than you take, so when you do need to ask for something you get a good punch.”

She was open about being a witch in high school, but she stopped going by “witch” after that, and only recently came back to the term.

“The further I’ve got in my career and the more I’m in a male-dominated field … the archetype of the witch has started to appeal to me more and more,” she tells me. “I think one of the reasons witchcraft appeals to people is that it gives you a sense of agency and it gives you a sense of control. It’s a very comforting idea, that you have a bit of control.”

Finally, Andrea Balboni, 46, is a sex, love and relationships coach who lives in London, although she was born in Massachusetts, the state where witch trials notoriously took place in 1692.

Without an educational background in science, her witchcraft-science balance is weighted towards the mystical, but that doesn’t mean she’s not deeply enthusiastic about the latter, particularly when it intersects with spirituality.

She speaks passionately about the intersection to be found at the virtual Love Abilities conference last month, where she attended a presentation exploring the neural basis of orgasm. She highlighted it to me because it lined up with the spiritual concept of cosmic orgasms. Dr Barry Komisaruk showed that women experiencing orgasm in the cervix and uterus reported seeing a shower of stars, or “images of universal spaciousness” – because of the nerves connected to, in particular, the cervix. In certain traditions sex can act as a way to connect to the divine, and here in this presentation was neuroscience officially documenting and explaining that experience.

Talking about her everyday relationship with spirituality and science, she said: “I have more access to my witchy side, it comes more naturally to me. The science will inform my work and then it’s always best to refer to a book or to a scientist or to a doctor about what’s actually happening.”

That’s not to say her work isn’t grounded in solid research: she uses, for example, attachment theory, a tool used by psychotherapists to understand people’s coping mechanisms and patterns in relationships and the concept of the “felt sense”, developed by philosopher and psychologist Eugene Gendlin, who found that the success of therapy depends on clients accessing a bodily feel of the issues that brought them there to begin with.

Brought up Catholic like Toffolo, Balboni says she found the religion “rigid”. She then encountered yoga for the first time in the 1990s, and moving from the US to Italy to, finally, London, she met several inspiring yoga teachers – but it was tantra that finally fit for her, as a complete belief system.

“I had no idea what tantra was, but in the very first class, I was like: this is my thing,” she says. “It basically gives you a roadmap to being human on the planet. Also, to what lies beyond as well, through experiential practice. It’s there when I started to explore sex and sexuality as sacred. It’s something that can open your body and your mind to something more.”

Tantra is a philosophy that emerged in India in the sixth century, and was subsequently part of the Indian fight for independence. It became popular in the UK and US in the 1960s, and can include yoga and visualisation to invoke tantric deities. It also removes distinctions between pure and impure, self and divine, which is where sacred sex comes in.

Sacred sexuality is partly about reframing sex – stripping away narratives that might deem it impure or shameful. It can also be about honouring yourself, your partner, or experiencing expanded states of consciousness, such as the cosmic orgasm.

“It’s the intention behind it, it’s the intention of the act as something that’s higher up, that’s uplifting, that is a pure expression of our love for one another,” she says. “Sometimes the sex act is offered up to divinity, so it becomes a devotional act as well.”

In 2020, McPhetres and his co-authors published another study. Again, it pitted religiosity against interest in and a positive attitude towards science. But this time, the researchers found that, across 60 countries, the negative correlation between the two was not always replicable. In places such as India, religiosity predicted greater interest in science. (Interestingly, in their 2016 study, Ecklund et al found India to be one of the countries with the highest religiosity – 94 per cent of scientists had a religious affiliation and were more likely to attend religious services that the general population.) McPhetres thinks there was about a 50-50 split between positive and negative correlations, but there’s something even more crucial: “It’s really weak in both directions,” he says. “I don’t think that, overall, there’s a clear relation.”

In the study itself, the authors wrote: “Prevailing theories and narratives suggest that religious belief necessarily leads to rejection of science. While the two accounts may sometimes offer contradicting narratives about some subjects, the present studies undermine these previous accounts and broader sociological accounts of scientific advancement undermining religion.”

“It’s easy to think of the other side as being contradictory or inconsistent or close minded,” Jonathon adds. “You see it in politics too, right? The other group’s always wrong.

“We need to learn to get along with each other. It sounds really cheesy but it’s the main point. Saying that religion sucks or science sucks – no one benefits from that in any way.”

The 2016 study says more or less the same. It found that, across eight countries, the percentage of scientists who claimed to be at least slightly religious ranged from 59 per cent in India to 16 per cent in France and therefore “whether one examines religious beliefs, practices, or identities, according to the religious characteristics of scientists, it is difficult to conclude that science and religion are intrinsically in conflict”.

A part of me always believed that magic was a science in itself, but since becoming disabled, it has all come together as one, because I feel like I’m on this spiritual path

Furthermore, the study found that most scientists across the eight countries thought science and religion were independent of each other, where being in conflict was a separate option. This is important, because of what the authors noted at the beginning: “The prevailing argument is that science and religion are in conflict because they represent different ways of understanding the world.”

But in actual fact, scientists – the people who are, presumably, most invested in science as a positive force in the world – believe that the different methods of understanding are precisely what negates the conflict.

And it seems that scientists who are witches think exactly the same about their beliefs and their work.

“Science is a tool for us to explain how things in the physical world work,” says Borealis. “Not everything in our world works really well with that method. It works incredibly well for what it works for. But something like emotions are very difficult to quantify.

“When I work, I’m using my rational brain and I’m trying to pick things apart and I’m trying to not be too attached to any one idea because in the scientific method you have a hypothesis and then you just try to break it, you try to prove yourself wrong.

“I think that having a clear separation in my life – I have my religious and spiritual practice and I have my work – I have this outlet for art and emotion and creativity that doesn’t need to be explained.”

She explains how meditation had helped her see when she was very emotionally and personally attached to an idea and to acknowledge it – and to keep that away from her work, because “if it breaks, it breaks”.

“I think it makes me a better scientist because it gives me a more mature understanding of how my emotions relate to my work,” she says.

Later, she adds: “I don’t think they are at odds to each other because how we emotionally experience the world is always going to be different from physics or something like that.”

Balboni says: “For me, everything is neutral. It’s the intention behind it, whether it’s in the realm of science, whether it’s within the realm of spirituality – whatever realm it’s in. It’s always neutral and then the use of it is what determines the effect of it.”

And of course science and magic can overlap successfully, as Toffolo has discovered.

“I don’t just blindly learn the hypnotherapy or the herbalism,” she says. “I obviously dig deeper into the hows, whys … I like to dispel myths because there’s a lot of those, particularly in herbalism.

“That was where the spiritual side of me and the scientist side of me really started to come together.

“A part of me always believed that magic was a science in itself, but since becoming disabled, it has all come together as one, because I feel like I’m on this spiritual path to use my science head to make a difference and to help people.”

Interest in witchcraft has ebbed and flowed before, making it even less likely that its appearance alongside anti-vaxxers is anything more than coincidence.

For example, Pam Grossman, host and creator of the Witch Wave podcast, told The New York Times she thinks there’s a resurgence of interest in the witch with every wave of feminism. We currently reside in the fourth wave. Witchcraft enjoyed peaks in popularity in the 1960s (second wave) and then again in the third wave in the 1990s (think The Craft, Blair Witch Project, Practical Magic, Hocus Pocus).

Whatever the pattern, it’s clear that we should be worried about anti-science. But what’s not clear is that witchcraft is in any way related to it.

The Pagan Federation’s Harrington strongly objects to being lumped in with anti-vaxxers: “To be put in the same sentence is absolutely disgusting, how anyone could say that is awful.

“They are people who have, actually, a need of a coherent belief structure. They’re a bunch of people for whom organised religion has failed, and when the internet has so much information that you can’t find the real stuff… they fall into believing things.

“Romanticism has not died away with science. You have got astronauts in space saying they’ve seen the face of God. You can’t do away with that.”

Romanticism is a nice way to look at it, because there really is a softer, more poetic feeling to all three women’s spiritual practices, when compared with their scientific work. Borealis talks of a realm for creativity and emotions and uncertainty. Toffolo’s practice is underpinned by enduring gratitude and devotion, it’s a space where she can literally follow her dreams and talk to lost loved ones. Balboni’s spiritual world celebrates love and sex and following the flow of the universe.

It doesn’t stop any of them from doing or appreciating science, because it’s not about opposition, it’s about balance.

As the light dwindles and winter creeps in, look up at the moon. Is it an embodiment of the goddess, moving through maiden-mother-crone as she waxes and wanes? Is it a huge rock moving at 3700kmph around the earth, upon which Nasa has just confirmed the presence of water? Could it be both?

Look up, and feel the autumn air against your skin, and enjoy the duality.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments