Turing Test: What is it – and why isn't it the definitive word in artificial intelligence?

A computer recently passed the iconic test for the first time this weekend - but is a 64-year-old thought experiment even relevant for today's computers?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The news that the Turing Test has been beaten by a computer for the first time could have significant implications for artificial intelligence – but just what is the Turing test and what does beating it actually mean?

The test was first proposed by the British mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing who, in his 1950 paper ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’, asked a simple question: ‘Can machines think?’

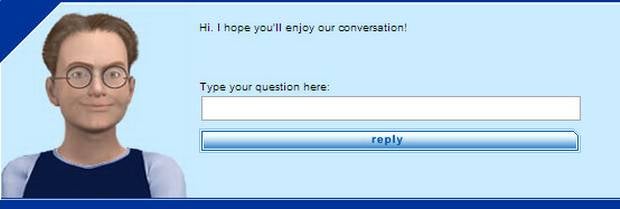

Turing later finessed this to ‘can machines do what we (as thinking entities) can do?’ and proposed his eponymous test as one way of finding out. In its most simple form the test has a human interrogator speaking to a number of computers and humans through an interface. If the interrogator cannot distinguish between the computers and the humans then the Turing Test has been passed.

There are many different takes on the test (in some variations the interrogator knows that one of the entities they are questioning is a computer – in others they don’t) but many computer scientists and philosophers have criticized its very premises for only assessing the appearance of intelligence.

The American philosopher John Searle famously challenged the Turing test with a thought experiment he called the Chinese room. Searle's suggestion was that a computer’s ability to conduct a conversation or convincingly answer questions is not the same as having a ‘mind’ or ‘consciousness’.

“Suppose that I'm locked in a room and […] that I know no Chinese, either written or spoken,” wrote Searle in 1980, adding that he would receive questions written in Chinese through a slot in the wall. He can’t read the characters, but has a set of instructions in English that allow him to respond to “one set of formal symbols with another set of formal symbols.”

In this way, Searle can respond to any questions submitted to him by simply following the English rules and selecting the right Chinese characters to return to his interrogator. If the rules he has are sophisticated enough then it would appear that he could speak Chinese – even though he has no understanding of the language.

Most criticisms of the Turing test as a measure of artificial intelligence follow similar lines, arguing that computers can use tricks and vast databases of pre-programmed responses in order to simply ‘appear’ intelligent.

For example, in the recent successful test the computer programme claimed to be a 13-year-old boy from Ukraine – two factors that could be used to excuse any grammatical errors in the computer’s replies as well as its ignorance of more specialised forms of knowledge (pop culture and the like). In addition, only 33 per cent of the judges 'Eugene' spoke to had to be convinced he was a human (Turing himself never specified a pass rate) and the conversation was only five minutes long.

For this reason (and many others) a lot of computer scientists no longer view the Turing Test as a credible way to assess artificial intelligence. However, that doesn't mean it's completely useless. A more stringent version of the test is currently the subject of a $20,000 bet between two legends of the tech industry, Ray Kurzweil and Mitch Kapor. In their rules the conversation must take place over three hours and two out of three judges must be convinced that the computer is a human - that's a pretty tough ask.

As it stands, the Turing test passed this weekend by 'Eugene' isn't insignificant (it certainly says a lot about the sophistication of our chatbots - which could be used in everything from scamming to therapy) but the main takeaway from this weekend's news is perhaps that the goal posts have moved. Turing's original test came from a time when computers the size of buildings were less powerful than our current smartphones - the fact that it's no longer as relevant as we first thought can be celebrated too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments