Website redesign: A design for strife

Why do we get so angry when the websites we love update their look? Anna Leach examines the battle between users and developers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When a staff member of the popular website Digg announced its new redesign and tentatively described it as "nice", users of the site hit back at the blog post with 2,500 comments – predominantly furious. Take this comment from spectralsounds: "Nice – if by nice you mean complete garbage. Even if they fix the bugs this is a horrible step backwards." It was the start of the site's downfall.

Bugs aside, you'd think fuming about layout tweaks on a website was just something for the nerds, the design fascists among us. Can normal human beings really get so angry about cosmetic changes on websites they don't own? The answer, resoundingly, is yes. All over the internet, people get furious about web design. And not just when it's bad. Often just when it changes. Even if those changes are for the better.

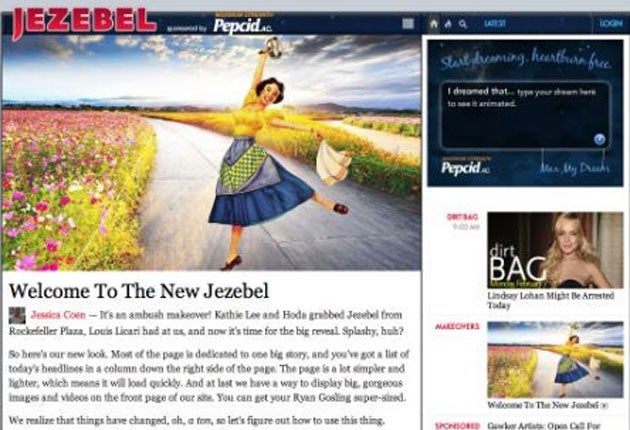

Witness the recent case of US web publishers Gawker Media. Gawker recently redesigned several of its websites: a change met by a storm of fury. Three weeks after the redesign, unique daily visits to the flagship Gawker blog slumped by 50 per cent from 500,000 plus to around 250,000 in the month after the redesign.

The blogosphere was alight with furious comments from readers too: "I never thought a web design could instill so much malice into me but the gawker redesign just makes me want to RAGE!" said Pjfry on Twitter. About sister site Jezebel, Sarah Wurrey tweeted: "Wow, the Jezebel redesign suuuuuuuuuuuuuuucks. Hate everything about it. May need to find a new entertainment blog to follow. Yikes."

For Americanchai the Gawker redesign wasn't just a different layout – it was a personal blow that reflected a general cosmic shift from order to chaos: "I'm so glad I found where people were bitching about Gawker/Jezebel redesign. I was pissed this morning! My head hurt like hell, it's Monday, I'm sharing my work space with somebody who is working on a completely messed up conference/training that is totally screwed up right now, so there's osmotic stress flowing into my workspace, and then I can't figure out how to read damn websites that are my usual mindless go-to's."

Ow.

The changes Gawker had made? Just a matter of layout, a new focus on pictures and videos at the expense of the traditional story list. Otherwise the content is exactly the same: same stories, same topics, same writers.

Two weeks later owner Nick Denton apologised and restored some former features such as comment replies. He's still betting the redesign will increase readership though – $1,000 to be precise – to technology writer Rex Sorgatz.

When Twitter launched a much-improved redesign, people filled Yahoo Questions, plaintively asking how they could go back to using the old one. On the traditional Google home page the total word count on the page is rigorously controlled. And that's because legions of hard-core Google fans will email in complaining if they don't: "61 – Getting a bit heavy, aren't we?" It's trimmed it down to 28 – most of the time.

Redesign rage happens offline too: when newspapers rearrange their features section or when the supermarket moves the fruit aisle around. But redesign rage is a lot more noticeable on the internet because you can leave comments there.

The impact certainly resonates further too – you'll probably still go to your local Tesco, wherever the tomatoes have been placed, but on the web, you might just click somewhere else. For web owners who rely on views for revenue, that's a death-knell.

Andy Budd and his company Clearleft have redesigned websites including Gumtree and he says that redesign rage is something he always warns his clients about. He often references New Coke syndrome: where a better-tasting new Coca-Cola recipe had to be withdrawn because customers reacted so badly to the change. The moral: we don't like new stuff. Even when it's better.

This resistance to change wells up from a subconscious reaction that goes back to our primal roots. The shock in the mind of a 1985 American cracking open a can to taste New Coke for the first time, is similar to what our Stone-Age ancestors might have felt if someone moved their favourite rock or rearranged the bearskins. It's an unpleasant disruption.

Jakob Nielson, the web design expert and lecturer on usability, describes it like this: "There is a well-documented psychology finding called the 'mere exposure effect', which says that humans will like something more simply from having seen it many times.

"The mere exposure effect probably evolved to help early humanoids cope with their environment: they would like members of their own tribe and dislike outsiders, and they would feel more happy being on familiar territory than on foreign grounds. And they would prefer eating foods that they had seen before. All good survival instincts, and thus traits that were passed down the generations to us."

For web design – the implications are clear – people will prefer an old design purely because they have seen it a lot. Budd has a different name for it, "loss aversion", but his explanation is very similar: "People expect the pain of losing something to be greater than the value gained from its replacement," he says. Consequently, new sites have to be significantly better than the old ones to overcome that initial subconscious recoil.

Love of the familiar can make us blind to its problems. "When we redesigned Gumtree we got a lot of comments like 'if it ain't broke, don't fix it,'" Budd says, "but people often don't realise when something is broke because they manage to work around it.

"It's like in my house," he explains, "I love my house – but there are a few cracks in the wall. I don't notice them because I've lived there for ever. But if I were trying to sell it and somebody came in, the first thing they'd notice would be those cracks."

It's also a question of ownership: you don't care about changes on sites you only visit once a year, but if it's your favourite blog – you do. "Often people feel so strongly connected to a website that they think of it as theirs," Nielson says. And this sense of loss and unfamiliarity in stuff you love can feel very unpleasant and provoke powerful reactions.

"Even if the change is really logical," Budd says, "it's kind of like people coming into your house and rearranging the clothes in your wardrobe. It means you can't find everything immediately. People feel frustrated because the thing that they got used to has changed."

Some redesigns are done so well that there isn't a backlash. Some sites such as Amazon and Facebook constantly redesign so that updates seem normal. Often, a backlash will fade and very people who protested so furiously, usually the dedicated superusers, will be first to love it again. Occasionally the backlashers have a point. Sometimes the new design is stupid.

"It's really really common for organisations to add unnecessary features," says Budd, enumerating the pitfalls of his trade. "Often they add unnecessary features because it is a marketing gimmick. Everyone wants to have more and more functionality, but often it doesn't actually help people. We try and avoid that gimmicky 'add-feature, add-feature' impulse.

"If a user feels when they go on to a new site that all the problems they had have been fixed, they'll be really appreciative. If they feel that someone has gone in and rearranged the furniture, changed the colours a bit and moved the navigation around, they're going to be frustrated because they're not getting any value, all they're seeing are cursory changes."

In that case, changes don't just add nothing, they actually take away from the existing site. In the words of another furious Digg user, Gracehead, commenting on the redesign: "THIS MAKES NO SENSE AT ALL. It's almost like a competitor redesigned the site just to bring Digg down and marginalise their enormous success through a bunch of nonsensical bells and whistles that mitigates the core functions that made the site popular to begin with!"

Er, back to the drawing board?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments