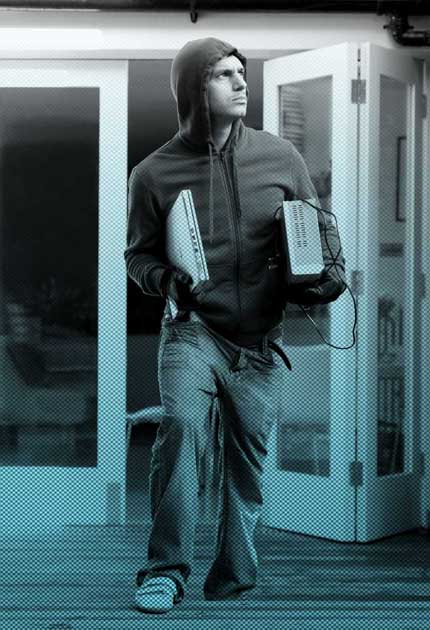

Tracking the technology thieves

If your laptop's been stolen or you've been mugged for your mobile, is there anything you can do to get them back – and catch the culprit? Yes, says Rhodri Marsden, who tracked his missing computer using the latest cyber-sleuthing software

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Somebody has swiped my laptop. Fortunately I know exactly who did it; my friend Anthony, who has taken it to a secret location, the idea being that I use modern technology to track him down and wrestle it back off him – and hopefully with a bare minimum of violence. Of course, when most people lose their gadgets or have them stolen, the new owner remains a mystery and the police have precious little to go on in order to retrieve it and mete out any appropriate punishment. But the new-found ability of satnavs, mobiles and laptops to be aware of their location and electronically spill the beans has established a new breed of software: programs that turn super-sleuth in order to reunite you with your beloved device.

The method by which GPS receivers pinpoint location is reasonably well-known; your satnav or mobile phone receives signals from four or more satellites, and by measuring the transit time of each signal it's able to calculate your position on the planet. But any device that connects to the internet – be it via Wi-Fi, a wired network, a wireless broadband dongle, built-in SIM card and so on – will yield up some information about its location. Take Wi-Fi; if your laptop or phone is connected to a wireless access point, a system called Skyhook can determine your location to within 20 metres by measuring the relative strength of signals from other nearby Wi-Fi points within your range. It's not fail-safe – particularly outside built-up areas – but it's often enough to detect precise locations. And almost any internet-connected device will, via the internet protocol (IP) address it's been assigned by the internet service provider (ISP), surrender additional valuable information.

Software such as Undercover, LoJack, GadgetTrak and others can make use of this location information to compile a dossier on the movements of a stolen device. In addition, other sneaky features can be enabled remotely to ensnare the unsuspecting thief: screenshots of what's being done on the laptop can be automatically retrieved (one such thief was famously caught after working on his CV on the machine he'd stolen) and, if it's equipped with a webcam such as Apple's iSight, snapshots can be transmitted, giving a very obvious indication of who might have stolen the thing. In addition, smartphones and laptops can be remotely erased or backed up once the software has been activated. "Perfect for a government employee who has accidentally left a computer full of sensitive data on a commuter train," says Derek Skinner, theft recovery services manager at Absolute Software, which produces LoJack, one of the market leaders.

LoJack and the like are something of a curious purchase; like insurance, we fork out for it while secretly hoping that we'll never have to use it. But, while detection rates can be pretty good – Undercover, manufactured by the Belgian company Orbicule, boasts an 80 per cent recovery rate among customers in the USA and western Europe – it's not exactly an insurance policy. Firstly, machines aren't clever enough to know when they've been stolen, so you're required to initiate the tracking process – problematic if you don't realise for a few days. Secondly, all this software depends on the thief using your computer or phone to go online. While it's likely that the computer will be used to access the internet, if there's no such connection established, there's not a lot the software can do. "There has been the odd customer who gets angry if a laptop can't be recovered," says Peter Schols from Orbicule, "but it's impossible to know where the computer is unless it goes online." Some software – including Undercover – comes with a money-back guarantee in recognition of this drawback.

But the third obstacle to being reunited with your gadget is the thorny problem of what to do with the evidence that the software has yielded up. You might now be aware that your laptop is connected to the internet from a block of flats on the outskirts of Luton, but attempting to go and retrieve it yourself would be foolhardy, and police forces have traditionally been suspicious of printouts crammed with information about the alleged thief that have been gathered by new-fangled means. But, according to Derek Skinner, this situation is changing. "Our software is now accredited with the Association of Chief Police Officers, awareness is growing, and we're forging successful partnerships with local police forces." Schols agrees. "ISPs are becoming much more helpful, and the police are catching up with the technology; they're realising that a lot of the hard work has already been done for them."

According to emailed reports from Orbicule, my laptop, equipped with the latest version of Undercover, has spent the day in the environs of High Wycombe – not entirely surprising, as that's where my chum Anthony lives. Location data reveals that he took it to work at the local university on Saturday, and it accompanied him back home in the evening; secret snaps from the built-in webcam confirm without a shadow of a doubt that he was the one using it, and screenshots reveal a webmail address he used and a selection of websites he visited – a veritable stack of information. However, had I installed LoJack instead, none of this information would be passed to me; their recovery services department – staffed by former police officers – take care of retrieval by working directly with the police rather than expecting us to do it. This is a boon when your stuff ends up overseas; if Anthony had posted my laptop to Hungary, the chances of me getting it back would be next to nil – but with LoJack there's still a fighting chance. "We recently had a laptop stolen from a school in Kent," says Derek Skinner, "only for it to appear connected to the internet in northern India. A contact of ours out there was able to liaise with the local police to get the computer returned. But if it ends up in a lawless area like Iraq or Afghanistan, it's as good as gone – the price of the software doesn't cover us being parachuted in to try and get it back."

Smartphones, with many of the capabilities of a laptop but in a much more portable form, have seen a flurry of track-and-recover apps appearing in recent months; while the comparatively low value of a phone might make its recovery less likely to be taken seriously by the police, Skinner notes that the recovery of one item can often lead to a more substantial haul. "Often it's a matter of looking for the criminality behind a theft – organised crime, gangs and so on." Schols also has a fistful of associated criminal cases that Undercover has had a hand in solving: "Our work has helped with drug arrests in Norway, a murder in the US, and the recovery of all kinds of stolen items along with the laptop that actually contained the software."

As these recovery techniques become better known, a recurring question from prospective customers is whether the thieves themselves are wising up to a point where they're savvy enough to bypass or disable the software to avoid detection. But Peter Schols, a man who has access to hard drives full of pictures of slightly gormless looking thieves betraying themselves by staring into the webcam of the computer they've just stolen, doesn't see it as an issue. "In reality," he says, "criminals are pretty stupid when it comes to computers." Fingers crossed that whoever nicked yours doesn't have a computer science degree.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments