Tomahawk missiles: What are the weapons dropped in Syria air strikes and what do they mean?

The US Navy holds thousands of the missiles, each ready to send a destructive and deadly message

The US has launched an unexpected attack on Syria, provoking destruction on the ground and divisions across the world.

To do so, it fired 59 Tomahawk missiles at the airbase. That brand of weapon is one that packs importance even beyond its deadly force – and one that indicates just how significant the decision to shoot them into Syria could be.

Each of those missiles cost $1.5 million, and in all, those 59 missiles cost $90 million. But the US army sees that price tag as worth it for a weapon that offers untold accuracy, destruction – and symbolic importance.

The Tomahawk missile has been in use since it was developed in the late 1970s. While it has undergone a range of different upgrades since then – adding in more recently developed technologies that help increase its devastating accuracy, for instance – it maintains the same basic design that dropped as part of the first Gulf War in 1991.

And the system for firing them is much the same too. The missiles – weighing in at 3,500 pounds and measuring 20 feet long – are flung at 550 miles an hour from the cruisers, destroyers and submarines that carry them.

When they’re on board their ships, they look like a huge, military sausage, and are placed into a launch tube ready to be shot out using their on-board rocket engine. But once they hit the air they open out 3.5-foot wings, allowing them to trundle along quietly, close to the ground, until they’re needed.

Strapped to the missiles are a set of explosives, ready to destroy wherever they land. But they also carry with them a host of technologies: GPS and other mapping tools, satellite connections and a navigation system and connection that means that they can loiter around in the air, awaiting the message that they should drop down – and be flown into specific locations once they are.

That is important when looking to respond to – and destroy – chemical weapons programmes run by the US’s enemies. Destroying such weapons isn’t a simple feat, and doing so in the wrong way can inadvertently spread the chemicals out and creating an attack of its own – and so the precision of the Tomahawk allows the military to fly into chemical weapons facilities in such a way as to destroy, not unleash, any capability.

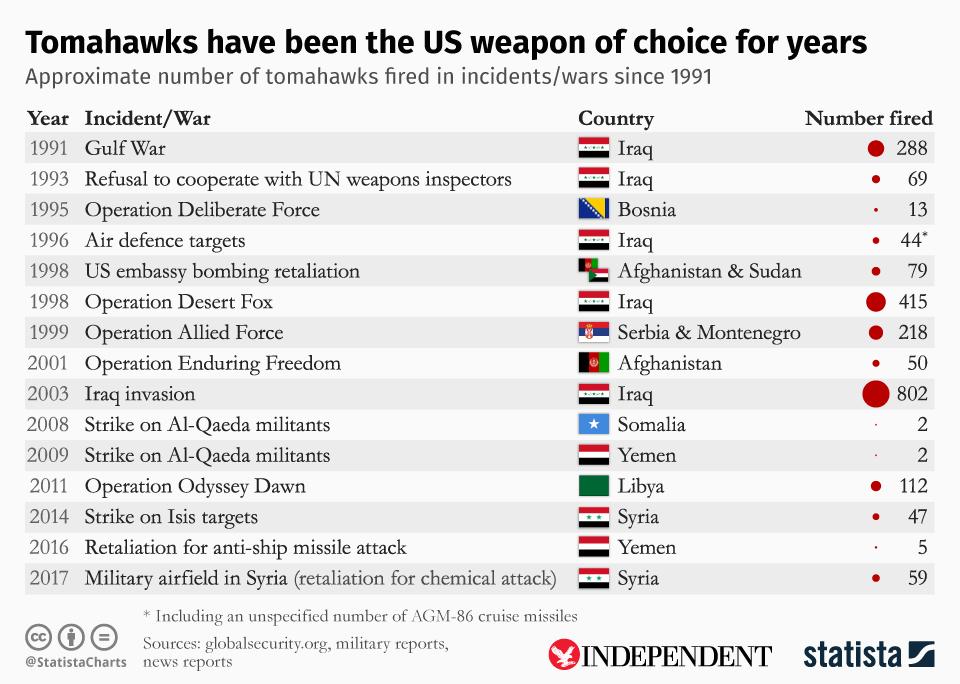

Doing so was intended as a message to Syria over its chemical weapons programme, and the fact that it had used it on its own people. It was far from the first time that US had done so – the country has used Tomahawks as warning letters in previous conflicts in Iraq, Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Sudan, Yemen and Libya.

The chart below/above, created for The Independent by statistics agency Statista, shows the times those weapons were used – and the sheer number that were fired.

The same thing that makes them so useful and so fearsome – their power, precision and price – is also what makes them such a significant statement. Preparing and firing a Tomahawk is a costly and careful procedure, one that is only activated when the US and its navy intends to make a destructive and deadly point.

"Though I'm no Trump fan, this is exactly the kind of response that should have met Assad and his forces the first time they used CW on an innocent population,” said Peter Felstead, editor of Jane's Defence Weekly.

“The fact that the US – and UK – didn't act then was shameful and probably led Assad to believe he could get away with it again.

“Tomahawk cruise missile attacks are a powerful message that US attitudes to that under the Trump administration have changed.”

And that message may not be finished: the country has a stockpile of Tomahawk land-attack missiles, to give them their full name. In all, the US Navy is thought to have more than 3,500 of them ready to fly, carried on ships around the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks