From surgical robots to 3D printers, this is how to do surgery in space

With plans to put humans on Mars in the near future, a medical emergency beyond the stars could spell disaster. Nina Louise Purvis looks at how to fix this problem

Earlier this year, it was reported that an astronaut in space had developed a potentially life-threatening blood clot in the neck. This was successfully treated with medication by doctors on Earth, avoiding surgery. But given that space agencies and private spaceflight companies have committed to landing humans on Mars in the coming decades, we may not be so lucky next time.

Surgical emergencies are in fact one of the main challenges when it comes to human space travel. But over the last few years, space medicine researchers have come up with a number of ideas that could help, from surgical robots to 3D printers.

Mars is a whopping 33.9 million miles away from Earth, when closest. In comparison, the International Space Agency (ISS) orbits just 248 miles above Earth. For surgical emergencies on the ISS, the procedure is to stabilise the patient and transport them back to Earth, aided by telecommunication in real time. This won’t work on Mars missions, where evacuation would take months or years, and there may be a latency in communications of over twenty minutes.

As well as distance, the extreme environment faced during transit to and on Mars includes microgravity, high radiation levels and an enclosed pressurised cabin or suit. This is tough on astronauts’ bodies and takes time getting used to.

We already know that space travel changes astronauts’ cells, blood pressure regulation and heart performance. It also affects the body’s fluid distribution and weakens its bones and muscles. Space travellers may also develop infections more easily. So in terms of fitness for surgery, an injured or unwell astronaut will be already at a physiological disadvantage.

But how likely is it that an astronaut will actually need surgery? For a crew of seven people, researchers estimate that there will be an average of one surgical emergency every 2.4 years during a Mars mission. The main causes include injury, appendicitis, gallbladder inflammation or cancer. Astronauts are screened extensively when they are selected, but surgical emergencies can occur in healthy people and may be exacerbated in the extreme environment of space.

Surgery in microgravity is possible and has already been carried out, albeit not on humans yet. For example, astronauts have managed to repair rat tails and perform laparoscopy – a minimally invasive surgical procedure used to examine and repair the organs inside the abdomen – on animals, while in microgravity.

Surgery by a robot controlled from another lab was successfully used to remove a fake gallbladder and kidney stone from a fake body

These surgeries have led to new innovations and improvements such as magnetising surgical tools so they stick to the table, and restraining the “surgeonaut” too.

One problem was that, during open surgery, the intestines would float around, obscuring the view of the surgical field. To deal with this, space travellers should opt for minimally invasive surgical techniques, such as keyhole surgery, ideally occurring within patients’ internal cavities through small incisions using a camera and instruments.

A laparoscopy was recently carried out on fake abdomens during a parabolic “zero-gravity” flight, with surgeons successfully stemming traumatic bleeding. But they warned that it would be psychologically hard to carry out such a procedure on a crewmate.

Bodily fluids will also behave differently in space and on Mars. The blood in our veins may stick to instruments because of surface tension. Floating droplets may also form streams that could restrict the surgeon’s view, which is not ideal. The circulating air of an enclosed cabin may also be an infection risk. Surgical bubbles and blood-repelling surgical tools could be the solution.

Researchers have already developed and tested various surgical enclosures in microgravity environments. For example, Nasa evaluated a closed system comprising a surgical clear plastic overhead canopy with arm ports, aiming to prevent contamination.

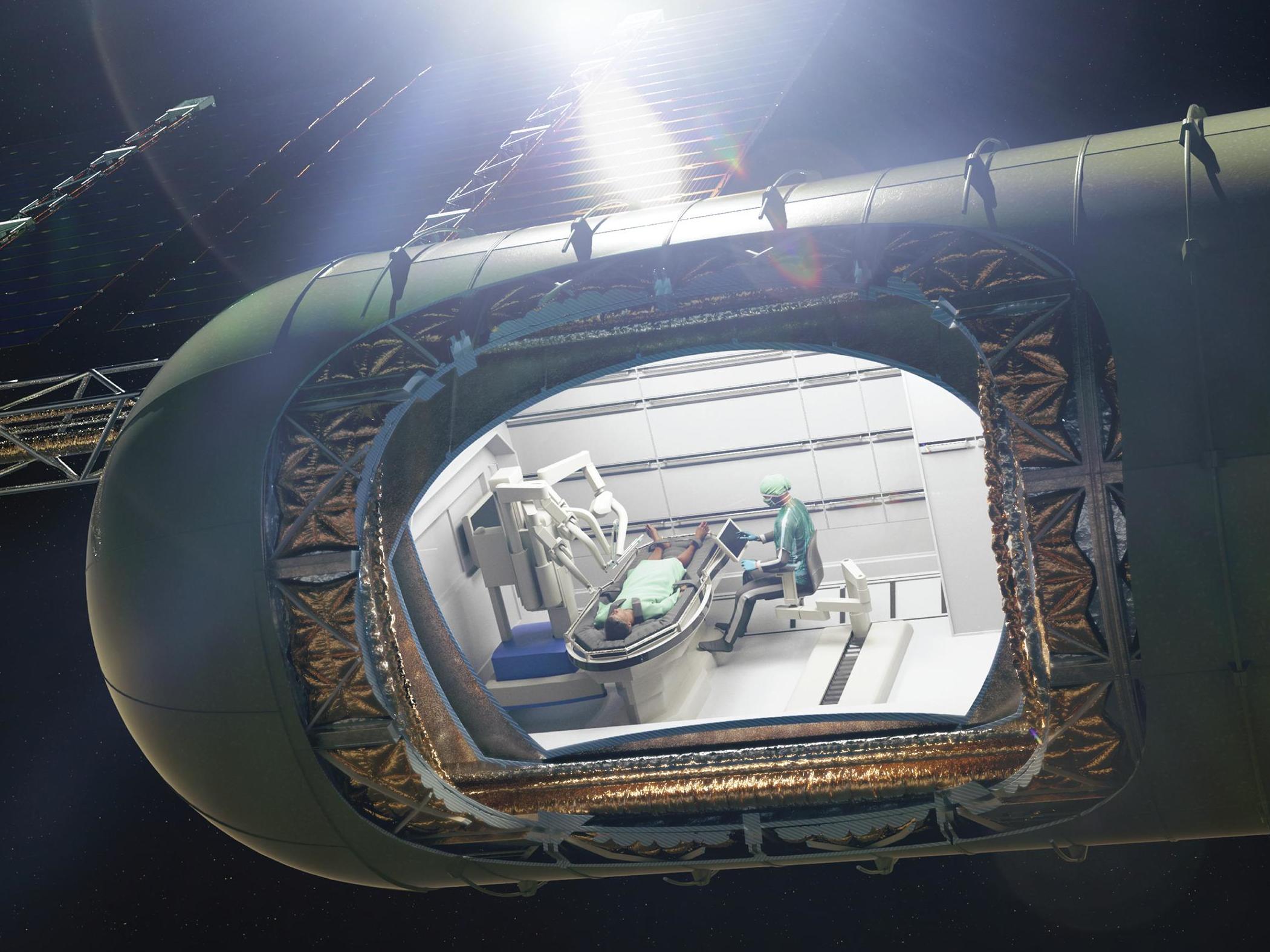

When orbiting or settled on Mars, however, we would ideally need a hypothetical “traumapod”, with radiation shielding, surgical robots, advanced life support and restraints. This would be a dedicated module with filtered air supply and a computer to aid in diagnosis and treatment.

The surgeries carried out in space so far have revealed that a large amount of support equipment is essential. This is a luxury the crew may not have on a virgin voyage to Mars. You cannot take much equipment on a rocket. It has therefore been suggested that a 3D printer could use materials from Mars itself to develop surgical tools.

Tools that have been 3D printed have been successfully tested by crew with no prior surgical experience, performing a task similar to surgery simply by cutting and suturing materials (rather than a body). There was no substantial difference in time to completion with 3D printed instruments such as towel clamps, scalpel handles and toothed forceps.

Robotic surgery is another option that has been used routinely on Earth and tested for planetary excursions. During Neemo 7, a series of missions in the underwater habitat Aquarius in Florida Keys by Nasa, surgery by a robot controlled from another lab was successfully used to remove a fake gallbladder and kidney stone from a fake body. However, the lag in communications in space will make remote control a problem. Ideally, surgical robots would need to be autonomous.

There is a wealth of research and preparation for the possible event of a surgical emergency during a Mars mission, but there are many unknowns, especially when it comes to diagnostics and anaesthesia. Ultimately, prevention is better than surgery. So selecting healthy crew and developing the engineering solutions needed to protect them will be crucial.

Nina Louise Purvis is a postgraduate researcher in space medicine and a medical student at King’s College London. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments