How we lost and found a massive supernova

In 1987 a star on the edge of our Milky Way exploded into a massive supernova, the results of this are still spreading through space, but nobody knew what happened to the star core, until now, writes Dennis Overbye

It was one of the great fireworks displays of recent cosmic history.

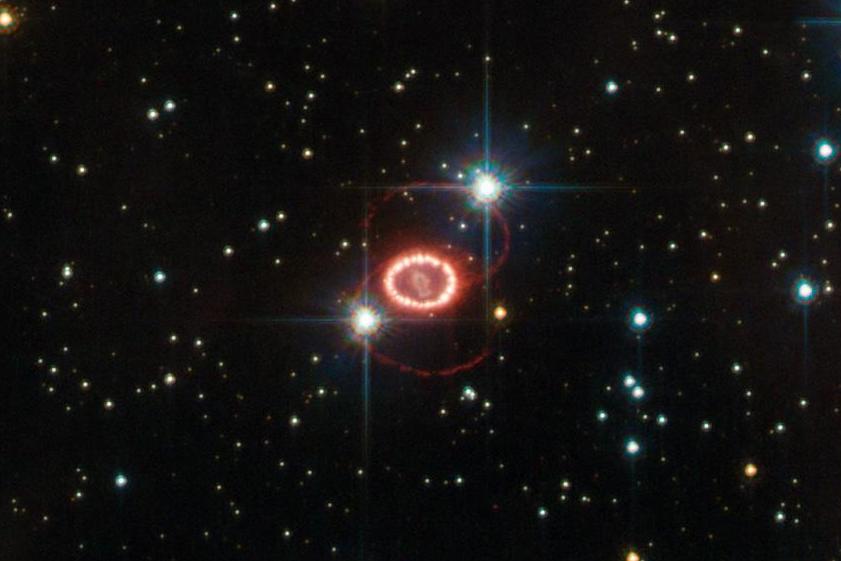

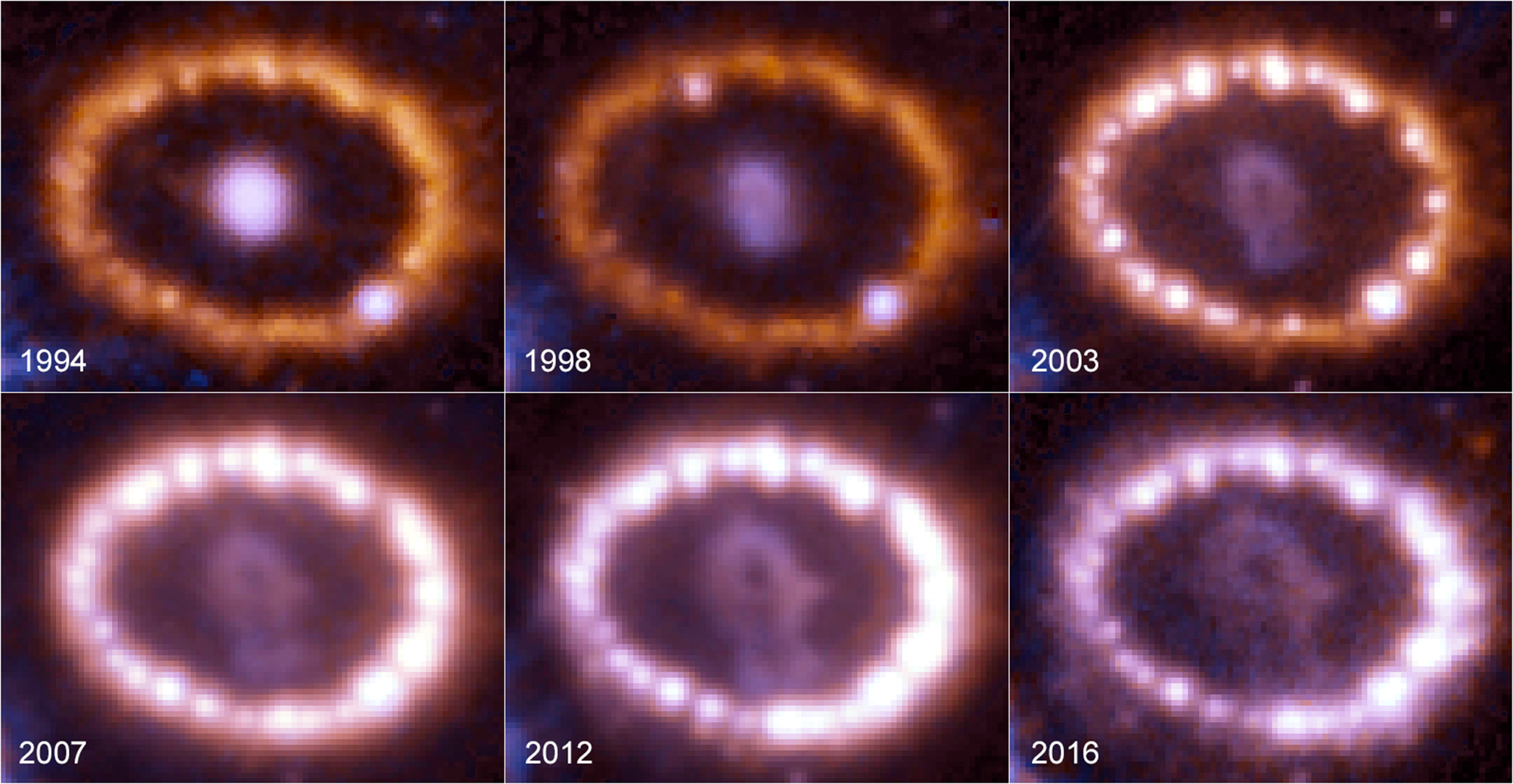

On 23 February 23, 1987, Earth time, a massive star blew apart right in front of the world’s astronomers, strewing ribbons and rings of glowing gas across the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy on the doorstep of the Milky Way. Today a smoke ring two-thirds of a light-year wide marks that part of the sky: almost 19 suns worth of glowing hot starstuff, some of it still radioactive, still spreading outward into the universe and diligently tracked by humans using instruments such as the Hubble Space Telescope.

But conspicuously missing from all those observations over the past 33 years has been any hint of the exploded star’s core, the demon seed of this cosmic catastrophe. Has it become a black hole? A dense nugget known as a neutron star? Did the star’s core just disappear? No one knew.

Until now.

Last autumn, a team of radio astronomers led by Phil Cigan and Mikako Matsuura, of Cardiff University in Wales, said they had found what they called “a blob” of dust emanating almost 100 times as much energy as our own sun in the supernova’s wreckage. Could the deceased star’s missing core, a mighty mite of ultrahot matter known as a neutron star, be hiding in there?

In May, a second team of theorists, led by Dany Page of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, concluded that the answer could be yes. He estimated that the neutron star left by the explosion would be 2 million to 4 million degrees Kelvin by now, enough to heat up the blob.

“We were very surprised to see this warm blob made by a thick cloud of dust in the supernova remnant,” Matsuura says. The team used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA, an array of 66 radio telescopes in the Atacama Desert in Chile. “There has to be something in the cloud that has heated up the dust and which makes it shine,” she adds.

If that heat source proves to be a neutron star, it would be the youngest example yet found of one of nature’s most extreme creations. Neutron stars are the densest stable configurations of matter in the universe – typically with half again as much mass as the sun, compressed into a ball the size of Boston. Think of all of Mount Everest shrunk into a teaspoon. Any more mass falling on a neutron star could tip it into the endless collapse of a black hole.

Spinning and magnetised, neutron stars can produce the lighthouse-like radio flashes known as pulsars. Nobody knows exactly how they are structured. Studying the evolution of neutron stars could give physicists insight into the behaviour of matter in the extreme. And of course it would confirm astronomers’ long-held notions about what happens when a star dies.

“The neutron star behaves exactly like we expected,” says James Lattimer, an astrophysicist at Stony Brook University in New York and a member of Page’s team. The teams published their results in a pair of papers in the Astrophysical Journal, most recently on July 30.

Astrophysicists reacted cautiously but enthusiastically to the report, noting that the neutron star in question remains invisible, at least with present technology. They also waxed nostalgic about the 1987 explosion, a seminal event in their careers.

“We’ve been waiting for something like this,” says Adam Burrows of Princeton University, who was not part of either team but has been studying this supernova for years.

Robert Kirshner, a supernova expert now at the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation in Palo Alto, California, says, “I’ve been studying SN 1987A for half my life.”

Daniel Holz, an astrophysicist at the University of Chicago, called the new discovery “sort of a halfway step”. Astronomers have seen something glowing, he says, but “it’s one thing for a bunch of theorists to say, ‘We think it probably formed a neutron star’ and an entirely different thing when astronomers actually find evidence that there is in fact a neutron star there”.

Supernova 1987A, as it is known, was the closest supernova to Earth in hundreds of years; the Large Magellanic Cloud is only 168,000 light-years away. Astronomers quickly diagnosed it as a Type II supernova, caused by the collapse of a massive star.

At its peak in the early summer of 1987, the supernova was pouring out as much energy as 250 million suns, which at that distance made it plainly visible and almost as bright as the stars in the Big Dipper, according to Kirshner, who saw it with the naked eye as an astronomer in Chile.

“But very red!” he wrote in an email.

According to astronomers, there are three possible fates for a star that has run out of fuel and died. It can end up as a hot dense cinder called a white dwarf, as an even hotter and denser neutron star or as a black hole, depending on its initial mass and other details of its composition.

The star that exploded was subsequently identified as a giant blue star known as Sanduleak -69° 202, which promptly vanished from the sky. In its prime it was about 19 times as large as the sun, which puts it in the range that astronomers think should produce a neutron star.

He likened it to a ‘modern holy grail’ — such explosions, after all, created the atoms of which Earth and our bodies are made

Reinforcing that conviction was the subsequent discovery that a few hours before the supernova was discovered, a pulse of two dozen lightweight subatomic particles called neutrinos had splashed into particle detectors on Earth. Messengers from the inside of the inferno, they had outraced the visible light in escaping the collapsing star.

“Neutrinos are indeed key to the supernova and neutron star process,” Burrows says.

As a massive star like this one undergoes its thermonuclear immolation, he notes, it develops thin layers of helium, oxygen, carbon and other newly minted elements. At the centre is a growing core of iron, the most stable element. When it reaches a limit called the Chandrasekhar limit, at which atomic forces can no longer support its weight, it implodes and then rebounds, leaving behind a hot, dense neutron star.

A shock wave ripples out through the layers. Accompanying it, and powering it by absorptive heating, are copious quantities of neutrinos, created from the energy of the collapse. Indeed, as much as 99 per cent of the energy of a supernova goes into these particles and out into the cosmos.

Neutrinos are famous for their spooky ability to pass through solid lead like moonlight through glass, but even neutrinos have trouble escaping the core of a dense proto-neutron star. It is the energy supplied by neutrinos, astronomers think, that provides the oomph to blow the star apart. If the neutrinos cannot emerge fast enough to heat an explosion, the supernova is likely to fizzle and the newly birthed neutron star will collapse into a black hole, Burrows says.

In the case of SN 1987A, they did escape. “People are pretty sure a neutron star formed from the yelp of neutrinos that were seen at the time of the core’s collapse,” Kirshner says. “But the ALMA result is the first indication that there might really be something in there – in this case heating the dust of the blob near the centre.”

Page says that neutrinos could also be produced by the collapse into a black hole: “It would be a very short signal, less than a second, while the star is falling into the black hole.” But, he notes, the pulse from SN 1987A lasted some 10 seconds. “So it needed to have some proto-neutron star surviving there for at least 10 seconds.”

The star could have later turned into a black hole, if much matter had fallen back on it, he says, but the fact that the supernova was such a strong explosion suggests that did not happen. As a result, the neutron star should have survived.

In July 2015, Matsuura and her colleagues scoured the supernova remnant at ultrahigh resolution with the ALMA. “We find that the dust emission in the ejecta is clumpy and asymmetric,” they wrote in their report.

The warm blob that is suspected of harbouring the neutron star was in a particularly dense region the team called the “keyhole”, where its molecular emanations could barely be detected. The blob was radiating at a temperature of 35 degrees Kelvin, they reported – just 35 degrees Celsius above absolute zero – whereas the surroundings were just 20 degrees Kelvin.

Astronomers had already targeted the keyhole as a likely location for the neutron star, if it existed. The supernova was asymmetrical, with more of the ejecta flying in one direction than another, and causing whatever was left of the core to recoil in the opposite direction at hundreds of miles per second. The core has now travelled about one-tenth of a light-year from the original site of the explosion, Matsuura says.

How will astronomers ultimately conclude whether a neutron star is actually there? If it turns into a pulsar, it will emit radio waves, Page says. If not, it might be emitting X-rays that could eventually be seen by the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

“In both cases, you’d need luck to have a little hole in the remnant that lets the radiation go through,” he says – or wait a few more decades for the dust and gas to disperse from the keyhole.

Matsuura says that she was not originally trying to find the neutron star. “I was still a schoolgirl at the time of the explosion of SN 1987A,” she says in an email.

Page was a graduate student at the time, and the event spurred him to become an astronomer, he says in an email. He likened it to a “modern holy grail” – such explosions, after all, created the atoms of which Earth and our bodies are made.

But, he adds, even after he became a professional astronomer, his means to solve the puzzle were limited. “I am a theorist, and I was just waiting for observers to find a first sign, some day,” he says.

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks