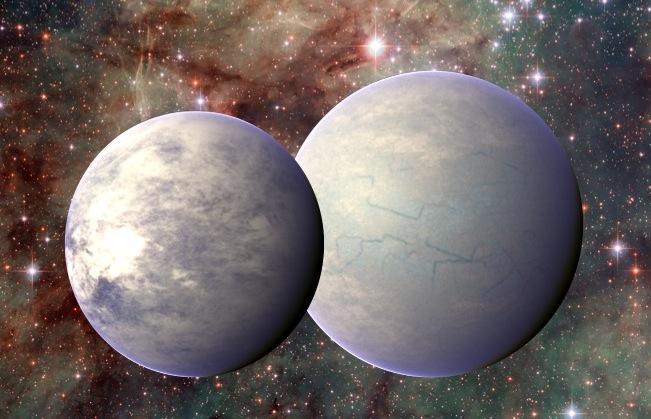

Scientists find two potentially habitable 'super-Earths' orbiting around our sun's near neighbour

Humans might be able to go and live on the planets

Two planets that orbit around a star like our own sun could support life, according to new research.

The two worlds at the edges of star Tau Ceti's "habitable zone" are part of a system of planets that are similar in size to our own. That is a breakthrough because it suggests that we might soon be able to find other planets that are habitable like our own Earth, researchers said.

The proximity of the planets and their similarity to Earth mean that they could eventually be a home for humans, according to the astronomers behind the research. But doing so might be a risky expedition.

The star appears to be circled by a huge disc of debris, which could suggest the worlds are being regularly hit by asteroids and comets.

Astronomers are especially excited by the discovery because the planets are as small as 1.7 times our size. That makes them the smallest worlds ever found around a star like our own sun, and has knock-on effects for the search for other planets like ours.

Their size was found by observing how much of a "wobble" the planets could exert over their nearby star. As planets pass by their sun, they lead it to move a little – and the size of that movement can be seen in the light that comes to Earth from the star.

Smaller planets require extra precision since the wobble is smaller and they can be harder to spot. And that precision is important to our ability to find other places that we – or other, alien life – could eventually live.

Lead researcher Dr Fabo Feng, from the University of Hertfordshire, said: "We're getting tantalisingly close to observing the correct limits required for detecting Earth-like planets. Our detection of such weak wobbles is a milestone in the search for Earth analogues and the understanding of the Earth's habitability through comparison with these."

Sun-like stars hold out the best hope of finding planets beyond the solar system that host life. Tau Ceti, a favourite destination of science fiction writers, is very similar to the sun both in size and brightness.

Like the sun, it has a "habitable zone", a narrow region around it where conditions are favourable for Earth-like life. Within the habitable or "Goldilocks" zone, temperatures are not too hot or too cold but just right for surface water to exist as a liquid. A habitable zone planet could have oceans, lakes and rivers.

Neither of Tau Ceti's "super-Earths" lie in the centre of its habitable zone. One orbits on the inner border and the other on the outer. The Earth is situated halfway between the middle of the sun's habitable zone and its inner boundary.

The astronomers analysed starlight wavelength data obtained from the European Southern Observatory in Chile and the Keck observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. Their findings are to be published in The Astronomical Journal.

Co-author Dr Mikko Tuomi, also from the University of Hertfordshire, said improved techniques were making it easier to distinguish between light signals caused by the presence of planets and stellar activity.

Two Tau Ceti signals previously identified in 2013 were now known not to have a planetary origin.

"But no matter how we look at the star, there seems to be at least four rocky planets orbiting it," Dr Tuomi said. "We're slowly learning to tell the difference between wobbles caused by planets and those caused by stellar active surface. This enabled us to verify the existence of the two outer, potentially habitable, planets in the system."

Additional reporting by Press Association

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks