Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine interview - director Alex Gibney on the fight to decide Apple co-founder's legacy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

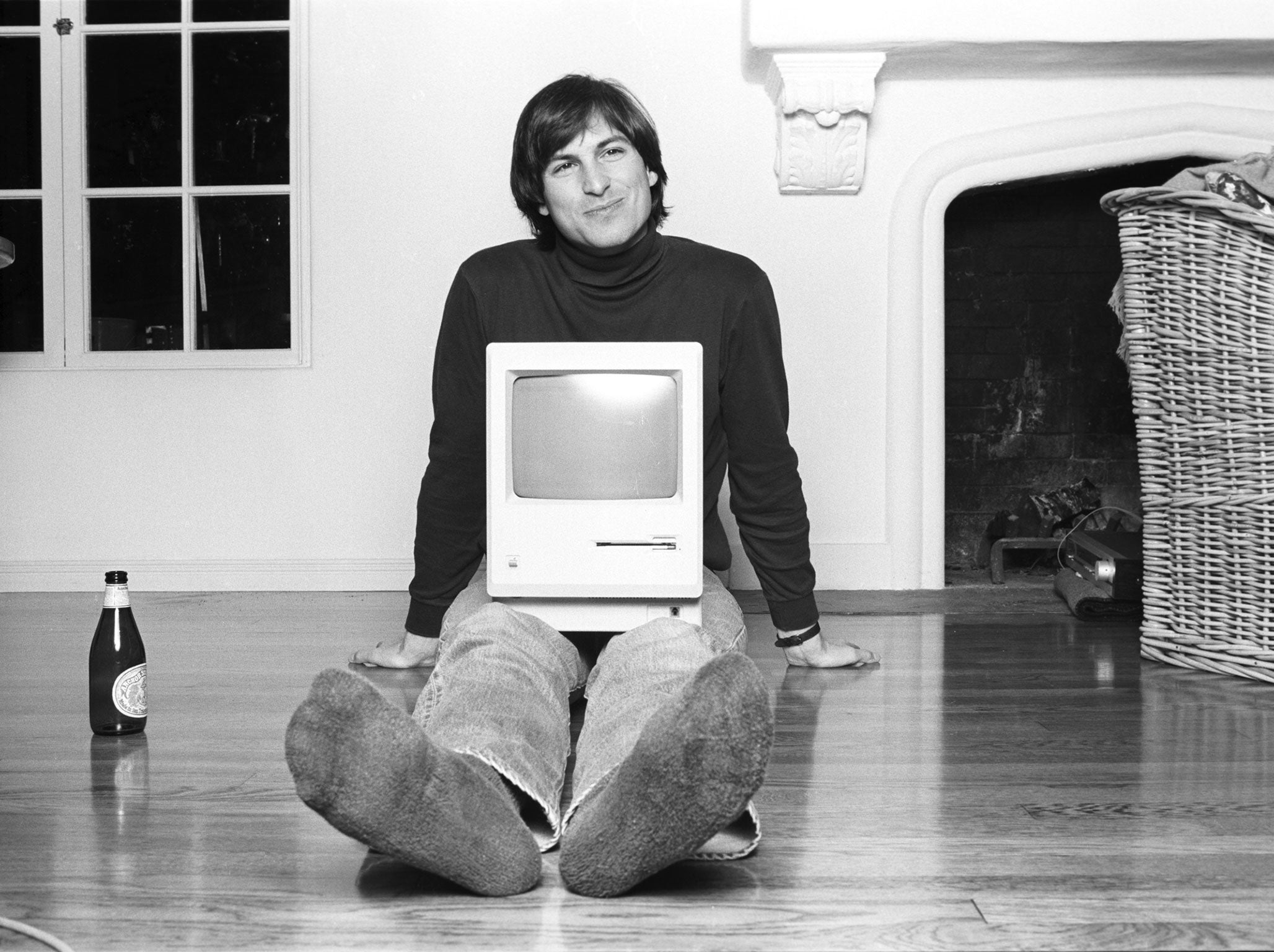

Your support makes all the difference.It’s just over four years since Steve Jobs died. And the arguments about how to decide his legacy have begun.

This year, there was a major book that some claimed finally told the complex story of Jobs’s death (Becoming Steve Jobs, by Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli, which was unauthorised but received subtle support from Apple's executives). That was joined by a major feature film, simply titled Steve Jobs, which was a commercial flop and focused largely on the Apple co-founder's relationship with his daughter. And Apple has shared its own recollections, with executives marking the anniversary of their old boss's death by telling stories among the company, which also features fans' recollections on its website.

Alongside those was Oscar-winning director Alex Gibney’s film, Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine. It is the most searingly critical of some of the ways that Jobs's story has been told, but also the only film that featured Jobs himself as some of the stoyteller.

All of those films and books are being made becuase of the popularity and importance of Steve Jobs's achievements. But they are also complicated by precisely how significant they were — and the difficulty of telling his story without telling our own.

It’s just after Steve Jobs’s death that Mr Gibney’s film starts. The film shows images of mourners. Gibney wonders aloud with a kind of confused half-scorn about how people can mourn his passing so publicly and how it can have such an impact on the culture — a response that has previously been reserved only for musicians and film stars.

Four years later, the film retellings of Jobs’s life began. There have already been two biopics — again, a treatment usually reserved for those in the arts rather than business leaders.

Jobs once said that for Apple “technology alone is not enough” — “it’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our heart sing”.

Technology alone isn’t enough to understand the legacy of Steve Jobs, either. His achievements were ostensibly in devices and computer services — but they were really in allowing people to use those in a way that made sense to them, for making and listening to music, for editing films, for reading and writing books.

So it makes sense that people are trying to work out exactly what that legacy is. And it makes sense too that people are trying to work that out through books and films, the same forms that Mr Jobs loved, did so much to empower and used so powerfully.

But why have all those films and books started to arrive in 2015? It’s been four years since Mr Jobs’s passing — is there something about this length of time that naturally leads it to be the beginning of a reconsideration of a person’s legacy?

“I don’t know why in particular it’s this year,” director Alex Gibney says. “I do think a revision is overdue. And I think also we’re beginning to understand partially as a result of what we’re seeing with Facebook and also Google — but also with Apple — that these companies have enormous power over our lives.

"They exert enormous influence, and I think we’re beginning to reckon with the idea that it may not all be that good and we better understand what they’re about. That we’ve bought into a kind of myth that they’re automatically all good and that’s not necessarily so.

“We’re all a little bit less innocent. I did intuit the idea that somehow by using apple products I was sticking it to the man, without realising I was working for the man. And so I think I’ve come to view the products themselves differently. And I think a number of things. I think the Edward Snowden episode was very interesting to learn how much the larger telecommunications companies had been working with the US government.

“Now there’s a certain amount of pushback. You’re seeing, as governments would have too, the enormous power of corporations. And we’re beginning at last to think critically about their social role, rather than just as an economic instrument for enriching shareholders.”

But that’s not just Mr Jobs or even Apple’s problem or achievement. Apple put the most transformative technology of recent decades into our pockets — but our feelings about technology over the last few years have mostly been shaped by the services that run on those phones. It’s Facebook and Snapchat — and the messages relayed over them — that often account for our worries, not the phones, computers or tablets that run them.

It’s likely that’s an unintended consequence of Jobs’s success as a storyteller, and a seller of devices, which relied upon and sold Jobs's own connection with the computers that he presented. That’s why the bosses of those services model themselves on Jobs, and it’s why the iPhone has come to be a symbol of them.

For a long time, Apple’s achievement in that respect seemed equivalent with Mr Jobs’s. The work he did to sell those phones became wrapped up with the phones themselves, such that it’s difficult to tell one story without telling the other.

But is it fair for that reason that we tell the story of modern technology by telling the story of Mr Jobs? Is it right that the man becomes a symbol of Apple and therefore the phones that sit in our pockets?

“I think the film tried to disentangle that a bit,” Gibney says. “You should come to understand by the end of the film that there were a lot of very talented people working at Apple. Their contributions were enormous and Steve Jobs was kind of the frontman.”

Jobs was — among his other talents — a master of the film form. Perhaps the most defining piece of video in computer history was created partly by Jobs – the famous 1984 ad that introduced the Macintosh . And he went on to be one of the driving forces behind Pixar, a film that had even more early success than Apple. (His achievements there have been little noted in either Gibney's or many of the other films.)

So the various films that are made have an extra requirement: re-depicting a man who already depicted himself, and Apple, with huge success. The 'Steve Jobs' film starring Michael Fassbender took as its set pieces events that had already been directed by Mr Jobs — the unveiling of products — and Mr Gibney's own portrayal uses archive material of Mr Jobs himself heavily.

“In part that’s why I had jobs himself co-narrate the film,” Mr Gibney says. “There’s a tremendous amount of Jobs in the movie. And so he speaks for himself, and he performs, sometimes quite magnificently.”

But the work of the film is partly to undo some of that great storytelling, or mythmaking, Gibney says. “It’s kind of seeing him in the green room instead of on stage.”

“Steve Jobs is the storyteller in The Man In The Machine,” says Gibney. “But he’s not the only one.

“There are counternarratives. And you present them together and his story doesn’t seem so unimpeachable."

“You can still be convinced by it. It’s really good! But at the same time you’re also seeing — because of the counternarratives, because of the other stories that are being told — you’re seeing the way the stage is built, the way the lights are focused and dimmed, and you see the stagecraft. And you see the visions, the divergence between what’s real and what is a façade.”

Still, the myth is powerful. And it's one that affects us all, for better or worse.

The Huffington Post’s Jonathan Kim said that the film “makes little attempt to portray someone who was, by most accounts, a complex, iconic, but all-too-flawed man who, over the course of his career, could be both inventor and thief, monk and businessman, brat and sage, tyrant and beloved leader, and managed to use those conflicting traits to both change the world and create the most valuable, influential, and admired company on the planet”.

That kind of screen – the flat screen on the iPhone or the iPad – is another kind of movie that’s being played out there, and it’s a movie that reflects: it’s kind of narcissitic for all of us.

“Instead, The Man In the Machine is focused largely on the thesis that Jobs was always and only a jerk, that people who enjoy Apple products and admire Jobs are idiots and cult members, and that the computer revolution that was born of Jobs' vision must inevitably contain the same ugly darkness Gibney feels is Jobs' defining trait, despite any evidence to the contrary,” Mr Kim wrote.

If there is unfairness in Gibney’s film, then it perhaps grows out of the fact that computer revolution was so powerful that it must have its dark side, and that dark side must be reflected in Jobs.

Apple commentator John Gruber has said that the film looked like “an attempt to fit the facts to a preconceived narrative, rather than craft a narrative from the actual facts” — because of the popularity and success of the products that Jobs made, that preconceived narrative can be our own.

At times, Mr Gibney notes in his film that — unlike his other films, about such powerful but distant subjects as the US military and the Church of Scientology — he is a part of this story, as an Apple fan and user. He readily admits to once having been convinced by the Apple branding, before moving to view it more sceptically.

“My narration is intended to be self-mocking at times,” Mr Gibney says. “And I include myself as part of the audience, even as I’m making the film.

Jobs created products — primarily the iPhone — that reflect right back at us. Some of what we see in that reflection isn’t as good as we’d like it to be, and it’s perhaps easier to blame the devices and the person who introduced us to them for that.

“I think his great genius was making us feel that those products really reflect ourselves,” Gibney says. “And so any time you criticise, whenever you criticise an apple product or you criticise jobs it’s as though you’re criticising the person who’s using the tool.

“And that kind of screen – the flat screen on the iPhone or the iPad – is another kind of movie that’s being played out there, and it’s a movie that reflects: it’s kind of narcissitic for all of us.

“We’re looking at it because we see the photos of our friends and families, and our own contacts. And it’s us!”

'Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine' is out on DVD & Blu-ray now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments