What does the poster boy for drug misuse really look like?

Carl Hart takes heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine – but he’s not a toothless down-and-out, he’s a college professor, which begs the question: is our view of drug-takers accurate? Ed Prideaux reports

Carl Hart likes taking drugs. It’s one of his favourite pastimes with his wife, Robin. “We always have a good time on methamphetamine,” he says. “We have a good time on MDMA, cocaine and the rest of these things. Our drug experiences are usually really good and illuminating.

“And we're better people for it.”

As well as methamphetamine – “crank”, “ice”, “crystal”, the devilish compound of Breaking Bad – Hart, 54, is especially fond of snorting heroin, which he’s used regularly for five years. After a long day at work, he says, a few lines of heroin by the fireplace can take the edge off like little else. It clarifies his thoughts, induces deep personal reflection, and pushes everyday pleasures to enhanced and ecstatic realms. Heroin makes him a “better person”, too, he claims.

Many readers will have built impressions of Hart already. In picturing enthusiasts of heroin and meth, our culture affords a rich bank of preset, cookie-cutter imagery. No doubt you may think Hart is “hooked”, likely unemployed, probably filthy, and possibly delusional. For how else could anyone claim that heroin and meth made them a “better person”? One in four would suppose that Hart probably didn’t have good parents. One in three wouldn’t let their kids play in the same park if he was there with his family. And if he was on Jeremy Kyle, Hart would likely get a dressing down as a leach and shirker of family duties.

Yet Hart is no Trainspotting poster boy. Muscular, teeth intact, a family man, he strikes an amiable and lucid conversationalist, for one. He’s also a professor of psychology at New York’s prestigious Columbia University – till 2019 the department head – and a global authority on the neurophysiology of drugs. He’s worked in the science of addiction and substance use for more than two decades, including with multimillion-dollar government grants.

This month, Hart is releasing his second book, Drug Use For Grown Ups. It’s a manifesto for the functional, “grown up” user of drugs, who meets their obligations, airs their emotional baggage, and enjoys getting high. Too often, Hart shows, we think of drugs in binary terms, as if the only choices – especially for meth, heroin and the like – are abstinence and addiction.

According to United Nations statistics, though, around 90 per cent of all drug use is basically unproblematic. It doesn’t trap and immiserate their users. It doesn’t ruin their lives. Drugs are simply one more tile in a larger tapestry of pastimes and things to do. Most illegal drug users in the UK, for example, don’t do so regularly and face little damage. It’s hard to believe, but Hart even performed his TED talk while high on meth, and did an interview the day before on heroin. Hart is willing to go to jail for his drug use, he says, and he’s not experienced any pushback from his Columbia employers.

Hart wasn’t always a drug user. For much of his career, Hart had spent years thinking like everyone else – even more so, in fact, given his upbringing in the Miami hood during the “crack epidemic” of the 1980s. Hart dealt drugs, carried a gun, had crack-addict cousins, and saw friends taken away in body bags. He became a scientist to solve the problems he thought drugs caused.

But across thousands of tests of different drugs, Hart came to realise that most users he met were entirely functional. They held down jobs, led relationships, and pursued meaningful hobbies. He tried methamphetamine for the first time at 40, and describes the experience in almost-beatific terms.

Hart’s case is provocative, certainly, but it’s worth noting that many of us are “functional drug users” already. Caffeine, a potent central nervous system stimulant, is a foundation block of daily life and the working economy. Alcohol, which we recognise as a risky drug – even riskier than cannabis, it seems – is consumed by thousands on a regular basis. One-third of Britons have smoked cannabis and 53 per cent support its legalisation. Of those who smoke the drug, 44 per cent increased their use during the first lockdown, with 21 per cent increasing by “a lot”.

After a long day at work, a few lines of heroin by the fireplace can take the edge off like little else

Yet when we broach “harder” drugs, it seems a category disconnect sets in place. Even cocaine, which one in nine Britons have used (and in which the UK is a continental leader), could be okay to a certain subset of the population. But “harder” drugs, which have been characteristic features of human history for thousands of years, like heroin, methamphetamine, crack, and PCP, paint an intrinsically darker picture in our minds. Among supporters of cannabis reform, in fact, support for their legalisation runs between just 9 and 16 per cent. These compounds are something else.

The case for legalising or decriminalising them isn’t a positive one, either. It’s most often addressed in the context of “harm reduction”, a best practice approach that seeks simply to minimise their dangers – whether from contamination, unsafe administration, or the damaging effects of criminal records. In fact, the case of Portugal, in which all drugs have been decriminalised, is sometimes held up by reformists precisely because drug use has fallen. Proponents of cannabis claim the drug can shift people away from the hard stuff. Drugs are set against each other: as competitors, almost good versus evil.

Hart doesn’t like our talk of harm reduction. It assumes that drugs are basically threats, he tells me, rather than the dispassionate mixture of benefits, costs and context-dependent risks they really present. And in and among the debates over drug policy, we keep forgetting that people do drugs for a reason. It’s because they produce benefits.

“The problem is that the experts, the so-called ‘drug experts’, haven’t [discussed the benefits]. We have disproportionately focused on the negative effects,” Hart says. “And so when people discover that they have primarily positive effects, then they reject everything that any experts have to say. I'm troubled by our drug experts. We call on experts if people rely on non-experts for their information. But when the experts are getting it wrong, that’s when we have a problem.”

Indeed, while we suppose science is independent of politics and popular opinion, the infrastructure in which its drug studies are designed and funded is coloured by prohibition. The National Institute on Drug Abuse, for example, assumes from its name and directive outwards that drug use is a problem to be solved. Scientists source grant money, Hart says, through pitching studies on risk – very rarely benefits.

In the UK, the equivocation of drug misuse with drug use itself is so embedded that the terms are used interchangeably in government statistics. Amber Rudd’s 2017 strategy for “tackling drug misuse” placed “prevention” – making sure that no young person ever tried an illegal drug to start with – as its core priority. At the same time, UK drug treatment budgets have decreased by nearly 30 per cent in recent years.

“People have to understand that life itself is not without risk,” Hart says. “That’s just part of the deal. As a human, there are potential risks and with any life worth living there are risks. You do your best to minimise those risks and you keep it moving.

“Well, we just had a president who is a threat to the world. So our system of selecting presidents is risky. But we try and put things in place in order to put checks and balances on people, like the current guy.”

The why and how of our stigma towards drugs is a complicated affair. In what’s a likely hangover from conservative Protestant ethics, we suppose any altered state sinful and sobriety intrinsically good. We think of drugs in pathogenic terms: the viscera of epidemics and outbreaks, their users classed as zombies. The UN’s 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, for example, is the group’s only convention containing the word "evil".

It’s not just drugs, though. Society likes legal drugs. It’s illegal ones that face the brunt of our stigma, and partly because they’re illegal. “Illegal drugs are immoral because they are illegal, and they are illegal because they are immoral” is how one researcher put it. More fundamentally, illegality feeds a “threat-based narrative” that lays the cultural and social groundwork for further prohibition, says Steve Rolles, a senior policy analyst at the Transform Drug Policy Foundation.

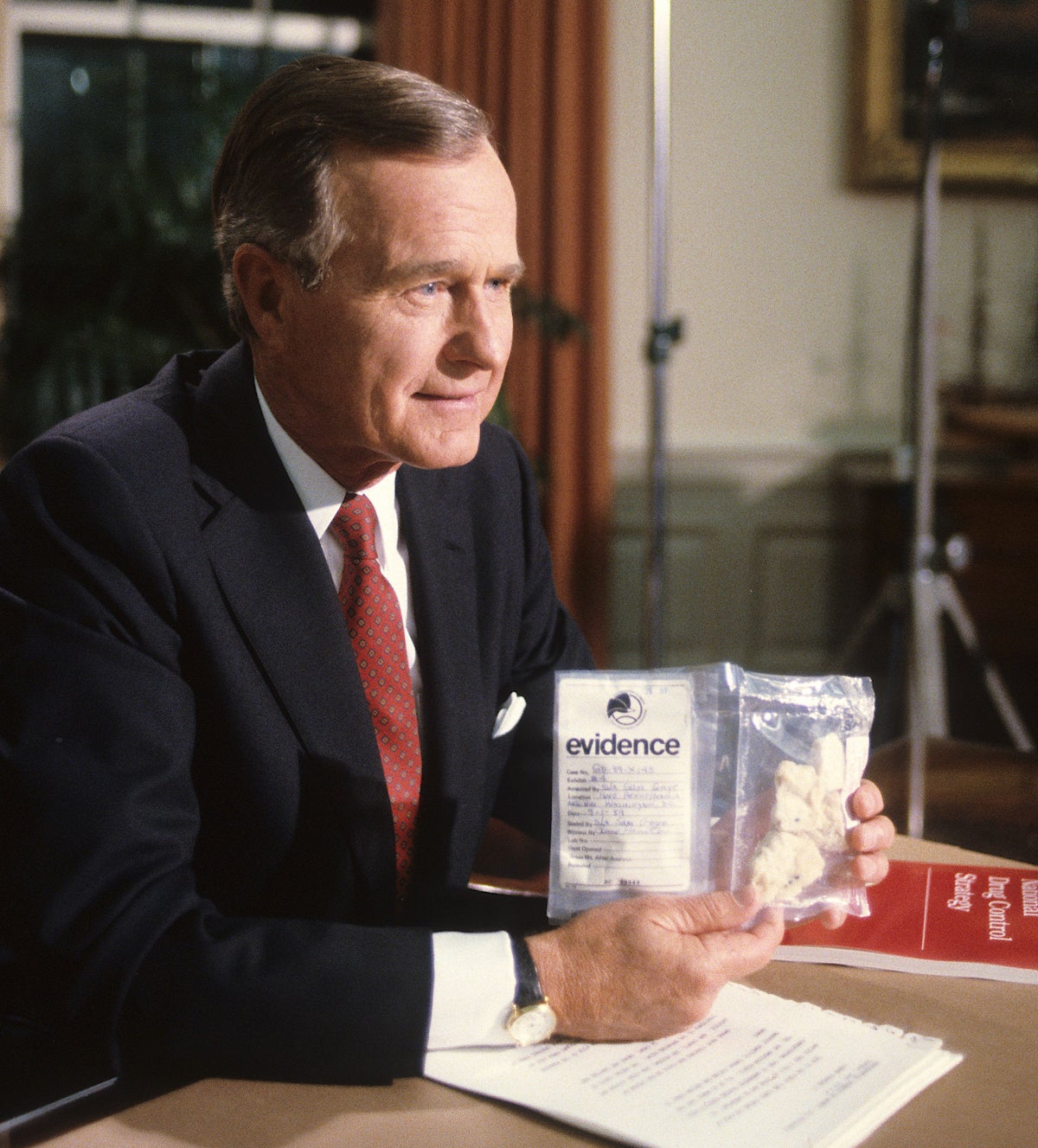

When drugs are conceived as “threats” – explicitly condemned and made illegal by the state – “you can then declare war against them”, Rolles says. “And so the whole narrative of prohibition is in very combative, very binary, moral terms of good versus evil. ‘Drugs are evil. They are a threat to society and our children and so on. And we will defend you from them.’

“And it moves the whole debate out of a rational policy space into essentially a war footing, where propaganda and extreme measures are justified and securitised approach to the issue is legitimised.

“Politicians have invested an enormous amount of political energy in these very binary moral narratives of good and evil in fighting the war. And they’ve kind of painted themselves into a corner. Any move away from those positions is synonymous with weakness or surrender or waving the white flag.”

And in the book’s more provoking passages, Hart suggests that many of our fearful assumptions about “hard” drugs may be flat wrong. What we forget, above all else, is the crucial importance played by the human subject. For every drug experience, the constellation of one’s environment, mood, diet and unique brain chemistry is as much a variant as the drug itself.

In controlled studies of MDMA and methamphetamine, Hart found that users were unable to distinguish the two. He found the same with methamphetamine and Adderall, a stimulant popular in the US on college campuses and given commonly to children. When a Nebraska congressman called it “the biggest threat to the United States, maybe even including al-Qaeda”, perhaps he was unaware that methamphetamine is prescribed as an ADHD drug, under the name Desoxyn.

Measured, cleanly delivered doses of pure heroin – stripped of the adulterants, especially fentanyl, that dog its street variants – are not physically toxic or liable to overdose. Getting addicted to any drug instantly is extremely rare. Heroin withdrawal, depicted in Trainspotting as something akin to torture, needn’t be too dramatic. Hart’s first detox, following a week and a half of low-dose heroin sniffing, led to a short spate of moderate flu symptoms. His second detox, coming after a three-week experiment in daily morphine use, was physically agonising, but ended quickly after consuming a tranquiliser. Hart gave a public lecture the following day, feeling slightly hungover.

“The weird thing is I notice people seem to react to it differently,” ML Lanzilotta, a poet, novelist, dancer and freelance journalist from Washington DC, says of heroin. She’s also a functional user of the drug, and came out publicly in an article for Filter, the topical drugs magazine, last year. “I didn't think of it as the greatest feeling in the world. To me, I always describe it as ‘extreme okayness’. It’s not the best feeling ever. Even at first, it’s just very calm and things that bother you don’t really bother you [anymore].”

Crack cocaine is especially demonised. Its reputation reached a nadir in the Eighties crack epidemic, when an estimated 10 per cent of African-Americans were addicted and drug-dependent “crack babies” were reportedly flooding inner city hospitals (both claims being untrue). Of the one in nine Britons who have sniffed cocaine, it’s worth asking how many were aware that crack is simply a different way of delivering the same molecule, albeit with a faster onset. If offered to vape alcohol rather than drink it, I’d imagine many of us would gladly give it a try.

The media holds a certain culpability. Addiction and user harm make for sexier stories, Hart writes, so journalists overlook the relative banality of most drug use. Scare stories are better copy. Salacious reports emerged in 2010 that Krokodil, a Russian heroin variant, ate its users’ flesh. That preparation contaminants, especially toxic phosphorus, really caused the wounds (and that desomorphine, the chemical behind Krokodil, has been admired and used for its medical application for pain relief) didn’t seem to matter. Popular memes suggesting bath salts – really synthetic cathinones, cousins of M-Kat – cause cannibalism were based on a fabricated story.

Our soft drugs can be undersold, too. Sold by some as a harmless, medicinal drug – and not least in the heavily marketed age of prospective legalisation – cannabis can be an unpleasant and jarring experience for many users. “The drugs that young people are most likely to use are alcohol, tobacco and cannabis. And that’s where our education for young people should really emphasise,” Hart says. “But it doesn’t. It goes everywhere, as if young people are likely to use heroin, which is just not true.

“And when we talk about cannabis education, we don’t emphasise [the risks] enough. For people who are inexperienced, the likelihood of experiencing extreme anxiety, paranoia, is not emphasised enough.

“There seems to be two dominant narratives: a person who uses drugs is either a criminal or a patient. And we don’t see that. We don’t see it in either way. Drug use is a very normal part of human life,” says Judy Chang, the executive director of the International Network of People Who Use Drugs, a pressure group fighting against global prohibition.

“If someone has a bad day, they drink alcohol. If someone wants to be social and have fun with their friends, they drink alcohol … Somehow if you take heroin for the same reasons that someone drinks, you’re deviant and a criminal.”

Chang is a functional user of opiates, too. They help her to relax, unwind and regulate emotion. So why haven’t we met more like her? “I think that the real concern with drugs that we're talking about – the recreational drugs, heroin, MDMA, cocaine, those things – is that middle-class drug users have remained in the closet for so long,” Hart tells me. “It has allowed this false narrative to be promulgated about drugs, that drug users are irresponsible degenerates.

“And in our films, in our media and just throughout the culture, this false narrative is propagated so fiercely and so effectively that people genuinely believe that opioid users, methamphetamine users, cocaine users … are [just] irresponsible people. But, in fact, the vast majority of those drug users are people like me, but they’re white. They are middle class and they are responsible and they’re doing well.”

At a drugs harm reduction conference in Portugal, Hart’s impassioned call for openness fell on deaf ears. Some were angry, many making excuses. Lanzilotta did something different, though. She first began dabbling in heroin amid the emotional stress of abusive relationships and a sexual assault. “It made it easier for me to handle that kind of stuff, for me to handle the fact that I was having nightmares,” she told me. “I would be afraid to sleep unless I took something to calm myself down.

“Over the last year or so, I would say I’ve only taken it when I'm just really depressed and I’m scared that I’ll attempt suicide or something. And it usually makes me cheer up.

“I’ve gone to doctors for years about being depressed, but most of the medications just didn’t work. It’s not exactly common, but not exactly unknown, that no matter what the doctors try nothing really seems to work. And I don’t know – I don’t think of heroin as some horrible thing. Because I do think it might have saved my life.”

Many people use conventional antidepressants with some success. A significant minority, in coming off the drugs, though, do experience physical and psychological side effects. And despite the presence of real chemical dependency, we wouldn’t dare stigmatise them as addicts, Hart points out.

His case isn’t too dissimilar, either. In three years as department chair for psychology at Columbia – a high watermark for professional success – he experienced “pathological stress levels”, with effects more sustained and deleterious to his mental and physical health than any drug he’d taken. The drugs were crucial in keeping him sane and together, Hart maintains.

While Hart can rely on a stable and lucrative academic career, Lanzilotta is more uncertain. “Being open about this kind of stuff is actually kind of horrible. You get harassment from strangers. It's hard to get a job and things if you say you've done drugs. So many people will be losing their job or ruining their career.

“I'm worried that if I want to rent an actual apartment instead of just a friend's spare room, the articles will come up and they'll say no. I know that for certain jobs I have applied to, they've seen the articles and said no. I don't know how long [the stigma] will last. It does terrify me and I do worry that they've kind of given up my future.”

Perhaps Hart’s book points at a deeper sickness. Indeed, that Elon Musk sleeps under his desk and occasionally works 120 hour weeks is cause for admiration as much as concern. The effects on his sleep alone would run tantamount, and probably exceed, the damaging effects of many risky drugs. In fact, much of the risk profile of stimulants like meth – psychosis, cognitive decline, physical degradation – comes precisely from prolonged neglect of sleep.

But when Musk took one puff from a joint – it’s not even clear he inhaled, too – on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast in 2018, not only did Tesla’s stock plummet by 9 per cent, but his apparently “bizarre” behaviour was bandied as evidence of an increasing instability and unworthiness to lead his own company.

Getting caught and convicted for possession of illegal drugs gives a criminal record, which can dog all future pursuits of housing, employment, relationships, civic membership, travel and adoption. Around half of all US prisoners are incarcerated on drug offenses. Being labelled a criminal robs drug users of vital social and personal capital. It pushes them to society’s edge.

Fifteen states in the US exercise the right to drug test benefits claimants. American parents, caught for drug use, have had their children taken away in acts of forced adoption. Drug testing in the workplace is a common practice in the US, too. A failed test can leave workers jobless and more likely to lapse out of functional use. The TUC has expressed concern that American firms are marketing workplace testing aggressively towards British businesses. And where the practice has been deployed in the UK, some claimed they were turned down from jobs because of a prescription drug and denied a chance to challenge the result.

The picture gets worse around the world. In the Philippines, users and dealers of methamphetamine have been murdered by government-sanctioned death squads. On his visit to the country, even Carl Hart faced threats and personal attacks from President Duterte. In China, where drug use is highly stigmatised and concentrated among the urban poor, traffickers face the death penalty, as in Saudi Arabia and Singapore.

Severe stigma and harsh sanctions can make for vicious cycles, in which problematic, non-functional drug use is further exacerbated. Stigma towards intravenous drug users in Russia, for example, is so extensive that they fear accessing treatment for HIV, especially women. For drug users in Pakistan, there is no standard treatment or rehabilitation. A quarter of addicts report being denied medical treatment and 28 per cent were recently turned away from hospitals.

Residential drug treatment is reportedly compulsory for Chinese addicts. A staff survey at Chinese methadone clinics revealed prevailing stigma towards clients, including beliefs that drug users deserve their addictions and to lose their jobs, their girlfriends should dump them, and that they would not allow drug users’ children to visit their homes.

It may be hard to come out, Hart says, but remaining in the closet pushes the cultural load on those more victimised – the poor, black and minority ethnic – to be the face of drug use. It doesn’t help that drug stigmas have been racialised from their very origin, says Juan Fernandez-Ochoa of the International Drug Policy Consortium.

Cannabis was a lightning rod for wider fears of Mexican immigrants and African-Americans, he tells me, with the drug implicated in fanciful scare stories of drugged-up rape incidents and murders. The racial legacy of drug prohibition is still clear to see. Ochoa points me to recent statistics over stop-and-search arrests, for example, which increased by 40 per cent during lockdown and with disproportionate effects on already overrepresented Bame communities.

In Drug Use For Grown Ups, Hart describes the case of Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old African-American shot by police, whom defence lawyers suggested may have been overly aggressive because of cannabis-induced psychosis. Their evidence? 1.5 nanograms of THC per millilitre in Martin’s blood: far too small a quantity for him to have been remotely addled, or even to have consumed the drug in the last 24 hours.

“Travelling all around the world, [I’ve seen] a protected class of drug users who know that they can get their drugs – whether from their physicians, whether from their connections – and they're OK.

“They’re OK with the current situation because they have access. And they don't give a shit about the people who are suffering, who are less privileged. And that's my real concern.” Hart doesn’t hang out with closeted drug users anymore. He’s not willing to spend time with those who lack the requisite courage – and especially politicians, some of whom he claims to have taken drugs with in the past.

The more functional users remain hidden, the more we misunderstand the mechanics of when drugs do go wrong, Hart suggests. In Scotland, a “Trainspotting generation” of long-term addicts is fuelling an unprecedented overdose crisis, with 1,264 people – far more than any other country in Europe – dying in 2020.

More than drugs alone, the real problem is one of mental health and systematic deprivation, says Dave Liddell, who heads up the Scottish Drugs Forum (SDF). None of these users can be described as functional, Liddell claims. An SDF survey of older drug users showed that none had jobs, 89 per cent had generalised anxiety, 95 per cent depression, 79 per cent lived alone, and some were experiencing the paranoid symptoms of psychosis. And while tempting to portray it as an “opioids crisis” along American lines, many Scottish overdoses are driven by toxic combinations of heroin and benzodiazepines, a drug class which addicts consume to manage anxiety.

The role of drugs as a catalyst and creator of social problems shouldn’t be overlooked. But, Liddell and Hart emphasise, the key is to address the underlying drivers that make descents beyond functional drug use likely. Focusing exclusively on drugs creates stigma, too, which creates major obstacles for addicts in getting clean. Significant minorities of Scottish survey respondents agree that addicts “don’t deserve our sympathy” (21 per cent) and their problems are the fruit of poor self-discipline (42 per cent), and half agreed that they wouldn’t want a neighbour with a history of drug dependence.

Methadone clinics are sometimes disparaged as “junkie boxes”, Liddell says, and he hears regular reports of addicts forced to wait for their prescriptions behind other people. Owing to shame and embarrassment, Liddell describes systematic, decade-long non-attendance rates of 40 per cent for many drug treatment clinics. For service users numbering around 1,300, Dundee clinics faced 452 unplanned discharges in a year.

Demonising drugs also takes away from obvious, albeit socially provocative, solutions – like safe consumption rooms, clean needle exchanges and the possession of naloxone (a remedy for overdoses) – on public service personnel. Boris Johnson made headlines last year in claiming that consumption rooms “drive criminality” and “encourage drug use”.

“Boris Johnson is living in the 1970s, early 1980s. [It’s like] in sex education, when people said giving out condoms would encourage sex. It’s the stupidest shit. I can't believe that people are in public service saying this kind of thing.

“I mean, people as adults have the right to make that decision. It's not his decision. And no public health officials should say stupid shit like that and get away with it.”

The SDF’s Dave Liddell is sympathetic to Hart’s approach. More than normalising functional use, though, he suggests that the immediate priority in Scotland is to socialise and destigmatise those who face problems. “There is a crossover between the two groups – people who start in a recreational fashion and then move over to problematic use – but that group tends to remain as recreational functioning users. And so how much would this help the population we're concerned about?

“Our view on reducing stigma is that the starting point should be on the 60,000 people with drug problems, in the services and the provision for that group.”

Functional use and addiction are slippery slopes. The variability at the heart of the drug experience – with the transient qualities of subject and lifestyle the true foundation – can cut both ways. Indeed, Hart, Lanzilotta and Chang may have sidestepped destructive addiction for now, but not everyone who samples risky drugs has enough resources, both emotional and social, to withstand addiction forever. This worries Adrian Crossley, who heads up the Addiction Unit at the Centre for Social Justice.

“If we are looking at what is a right message to the public, what is good for our society and our community, banding messages like ‘heroin makes me a better person’ is more than a little bit problematic,” he says. It’s like saying gambling makes you a better person, he adds: technically possible, but its bearing on gambling addicts isn’t something to celebrate.

“What we should remember is that stigma is also felt by people with alcohol abuse. The guy in the doorway drinking cider feels that same stigma”, Crossley emphasises.

“He is ostracised by society. And the guy who somehow got his whole family thrown out of the house because he was betting on online poker. These guys suffer a stigma, too, because it's a loss of control. It's a loss of contribution to society that we can be extremely judgemental about. Massively unfairly, because at the heart of some of this stuff is sometimes trauma and disadvantage.

“I don’t think having a pint is alcoholism. I don't think smoking a joint is an addiction. And I don't think, if you look at the statistics, you're much more likely as a consumer of alcohol to become an alcoholic than a consumer of cannabis, to become addicted to cannabis. But that doesn't really get us anywhere, in my view, when I talk about addiction. I'm talking about the minority, the important minority.”

Prior to any emphasis on legal changes, Crossley suggests, we need to have serious conversations about the deep roots of all addiction, including drugs, alcohol and gambling: things like community, cohesion and identity. Even conservative moves like diversion schemes, for example, in which young drug offenders are nudged away from punishment and towards upskilling, “have to be within the wider context of broader social engagement and a system. Whether or not a kid can stay in his block and smoke cannabis and call it a right, it's really not a helpful conversation.”

Drugs are only growing in contemporary relevance. Fifty years after Nixon declared the War on Drugs and key legislation banned their use, it looks like the prohibitionist tides are finally turning. Federal cannabis legalisation in the US is a matter of time, Transform Drug Policy’s Steve Rolles predicts. Promising changes are underway in the EU and South America. Psychedelic drugs are rapidly gaining ascendancy in psychiatric circles, and may be up for mass clinical licensing in just a couple of years. Joining other pioneers in Portugal and Switzerland, Oregon recently decriminalised all drugs.

These changes, welcome to Hart and other drug reformists, are posting red flags for the CSJ’s Adrian Crossley. While cannabis is no more harmful than alcohol, this doesn’t provide automatic grounding for its legalisation. “Alcohol is not a bastion of how beautiful and effective regulation can be. You just have to live with a certain degree of hypocrisy, and understand that you inherit the world that you were born into.

“And the question is, 'Do we need another problem?' If we've got one problem and we want to have a pure logical position, we’ll say, 'Well, all of those things should go in.' OK, that's beautiful logically, but is it good for our lives? No, it's not. I'm not introducing a new problem to justify having one already. That doesn't make any sense to me at all.”

For Hart, though, drug legalisation is a simple matter of freedom. Beyond the empirics of drug harm – and even their benefits – Drug Use For Grown Ups asks whether independent, private individuals can make decisions for themselves, beyond the purview of politicians and policymakers. This is the be-all and end-all, and Hart has little time for the “pragmatism” that can blight attempts at reform.

“This is my right to put into my body what I choose to do so long as I don't bother anybody else. It's quite remarkable that people stand for the government, the state, telling them what they can put in their body,” Hart declares. “It's f***ing remarkable to me when I really think about it. It's like you saying to me, I can only have one sugar in my tea. What kind of s**t is that? That's crazy.”

Hart’s call for honesty on drugs is a welcome one. Whether proponent or firm opponent of drug policy reform, greater transparency has to be a good thing. If only for healthier relationships, a more authentic depiction of self, and to take drugs into a truly rational space for political discussion, telling the truth about the when, why and how of our drug use spells a necessary leap for our culture. Let’s start small and see where it takes us.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments