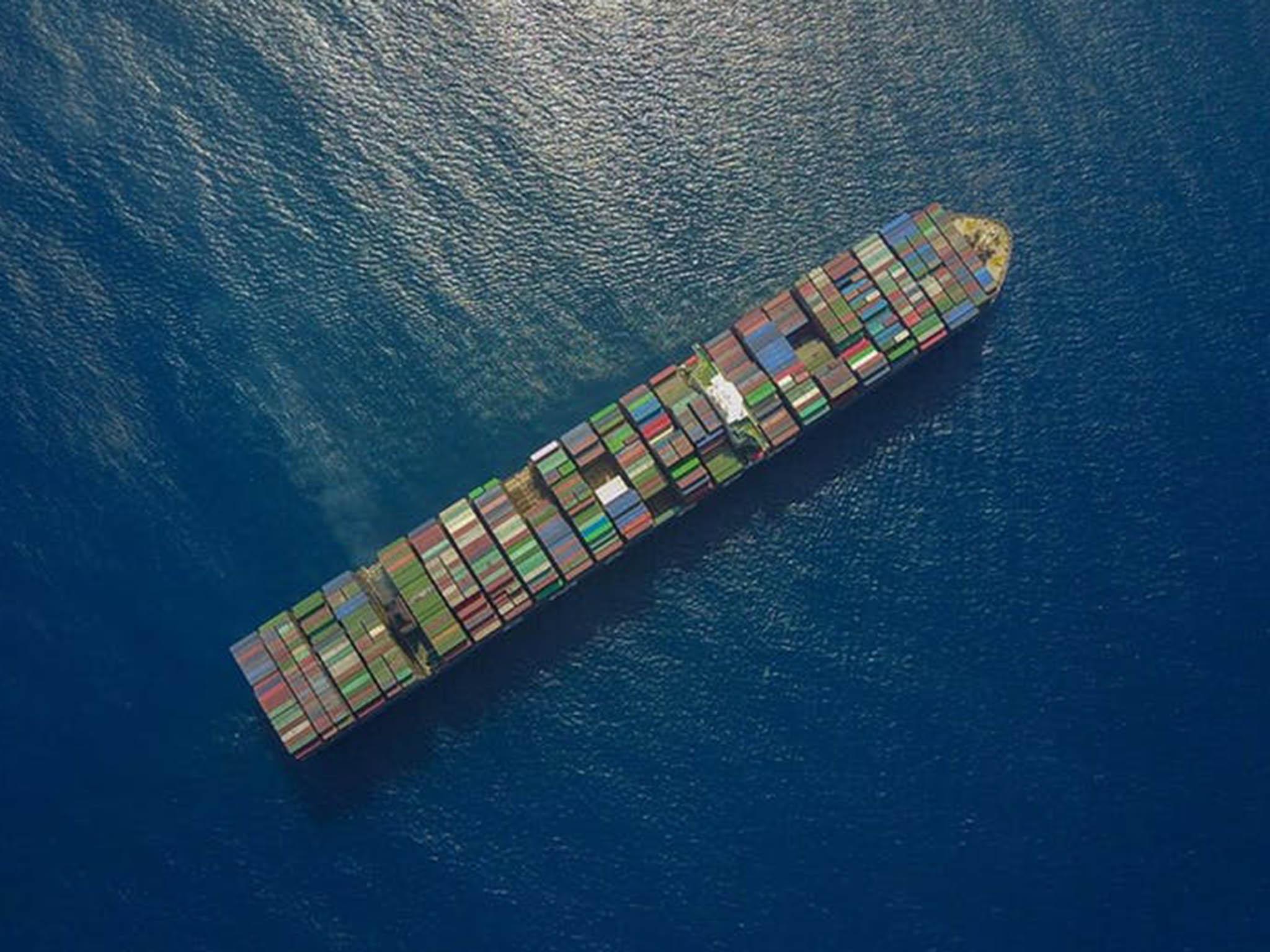

50,000 ships worldwide are vulnerable to cyberattacks

Vulnerabilities in shipping show how far the industry has to go but proper cyber security is more complex than you might initially think

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The 50,000 ships sailing the sea at any one time have joined an ever-expanding list of objects that can be hacked. Cybersecurity experts recently displayed how easy it was to break into a ship’s navigational equipment.

This comes only a few years after researchers showed they could fool the GPS of a superyacht into altering course. Once upon a time objects such as cars, toasters and tugboats only did what they were originally designed to do. Today the problem is that they all also talk to the internet.

The story so far

Stories about maritime cybersecurity are only going to proliferate. The maritime industry has been slow to realise that ships, just like everything else, are now part of cyberspace.

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO), the United Nations body charged with regulating maritime space, has been late and somewhat slow in considering appropriate regulation when it comes to cybersecurity.

In 2014, the IMO consulted their membership on what maritime cybersecurity guidelines should look like. Two years later they issued their interim cybersecurity risk management guidelines, which are broad and not particularly maritime specific. And now, unsurprisingly, ships are being hacked.

Complexity of the maritime industry

There are several core issues that make cybersecurity for the maritime industry particularly challenging to address.

First, there are many different classes of vessel, all of which operate in very different environments. These vessels tend to have different computer systems built into them. Significantly, many of these systems are built to last more than 30 years. In other words, many ships run outdated and unsupported operating systems, which are often the ones most prone to cyberattacks.

Second, the users of these maritime computer systems are constantly in flux. Ship crews are highly dynamic, often changing at short notice. As a result, crew are often using systems they are unfamiliar with, increasing the potential for cybersecurity incidents relating to human error. Further, the maintenance of onboard systems, including navigational ones, is often contracted to a variety of third parties. It is perfectly possible that a ship’s crew have little understanding of how onboard systems interact with each other.

A third complexity is the linkage between onboard and terrestrial systems. Many maritime companies stay in constant communication with their vessels. The cybersecurity of the ship is also dependent, then, on the cybersecurity of the land-based infrastructure that makes this possible. The implications of such dependencies was made clear in 2017 when a cyberattack on the systems of AP Moller-Maersk resulted in cargo delays across their entire fleet. This is particularly challenging for the IMO, which can govern the likes of port regulations but have very little control over the wider systems and processes of maritime operators.

Steps in the right direction

In 2017, the IMO amended two of their general security management codes to explicitly include cybersecurity.

The International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS) and International Security Management Code (ISM) detail how port and ship operators should conduct risk management processes. Making cybersecurity an integral part of these processes should ensure that operators are at least conscious of cyber risks.

Hopefully, this is the start of a more holistic approach to maritime cybersecurity regulation. The knowledge gained from these new cyber risk assessments may enable the IMO to develop a broader set of cybersecurity regulations.

There is a lot of low-hanging fruit to be picked, for example by harmonising some equipment requirements with existing cybersecurity standards adopted by other sectors.

Turning the ship around

The maritime industry is undoubtedly behind other transportation sectors, such as aerospace, in cybersecurity terms. There also seems to be a lack of urgency to get the house in order.

After all, the cyber-specific amendments to the ISM and ISPS don’t come into force until 1 January 2021, and they only represent the beginning of a journey. So the maritime industry seems particularly ill equipped to deal with future challenges, such as the cybersecurity of fully autonomous vessels.

On the positive side, the slow and steady approach to development of cybersecurity regulations at least provides the opportunity to learn from other sectors and fully understand maritime cybersecurity risks, rather than make hasty ill-informed decisions.

Development of robust maritime cybersecurity regulations is going to be a very slow, and possibly painful, process. But the ship has started turning.

Keith Martin is a professor and former director of Information Security Group. Rory Hopcraft is a PhD researcher both at Royal Holloway, University of London. This article first appeared on TheConversation.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments