Scientists use radio telescope to find hidden ‘super planet’

Radio emissions have only been detected from a small number of brown dwarfs

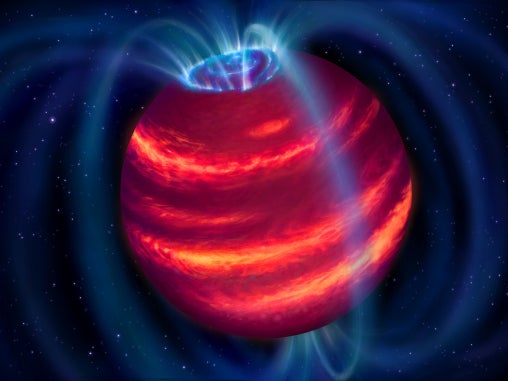

Astronomers have discovered a cold brown dwarf – otherwise known as a “super planet” – for the first time using a radio telescope.

Brown dwarfs are vast, sized between 15 and 75 times the mass of Jupiter, and have gaseous atmospheres similar to some of the planets in our solar system. They are also often known as “failed stars” because of the way that they shine.

Planets shine by reflecting light, while stars shine by producing their own light. Despite being so big, brown dwarfs are not able to sustain the nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium – which causes stars to shine – hence their name.

This brown dwarf, classified BDR J1750+3809 and named “Elegast”, is the first substellar object to be detected through radio observations. Usually, these stellar objects are detected via infrared sky surveys.

While brown dwarfs do not undertake fusion reactions, they do emit light at radio wavelengths in a similar way that Jupiter does – accelerating charged particles like electrons to produce radiation including radio waves and aurorae.

Radio emissions have only been detected from a small number of brown dwarfs, and all of those had been detected by infrared surveys beforehand.

Discovering this brown dwarf through radio telescopes shows that astronomers can detect objects too cold and faint to be picked up by infrared surveys. This opens the doors to the detection of other bodies like free-floating gas-giant exoplanets.

“We asked ourselves, ‘Why point our radio telescope at catalogued brown dwarfs?’” said Harish Vedantham, lead author of the study and astronomer at ASTRON (the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy).

“Let’s just make a large image of the sky and discover these objects directly in the radio.”

Elegast was discovered using the data from the Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR) telescope in Europe, and then confirmed using telescopes on the summit of Maunakea in Hawai’i.

The new research was published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters on 9 November, authored by Vedantham and co-authored by astronomer Michael Liu and graduate student Zhoujian Zhang.

“This work opens a whole new method to finding the coldest objects floating in the Sun’s vicinity, which would otherwise be too faint to discover with the methods used for the past 25 years,” said Liu.

This discovery could also help astronomers measure exoplanets’ magnetic fields, as cold brown dwarfs are the most similar bodies to exoplanets that scientists can measure with radio telescopes.

As such it could shed new light on predicting another planet’s magnetic field, which is vital in determining its atmospheric properties and the evolution of other worlds.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks