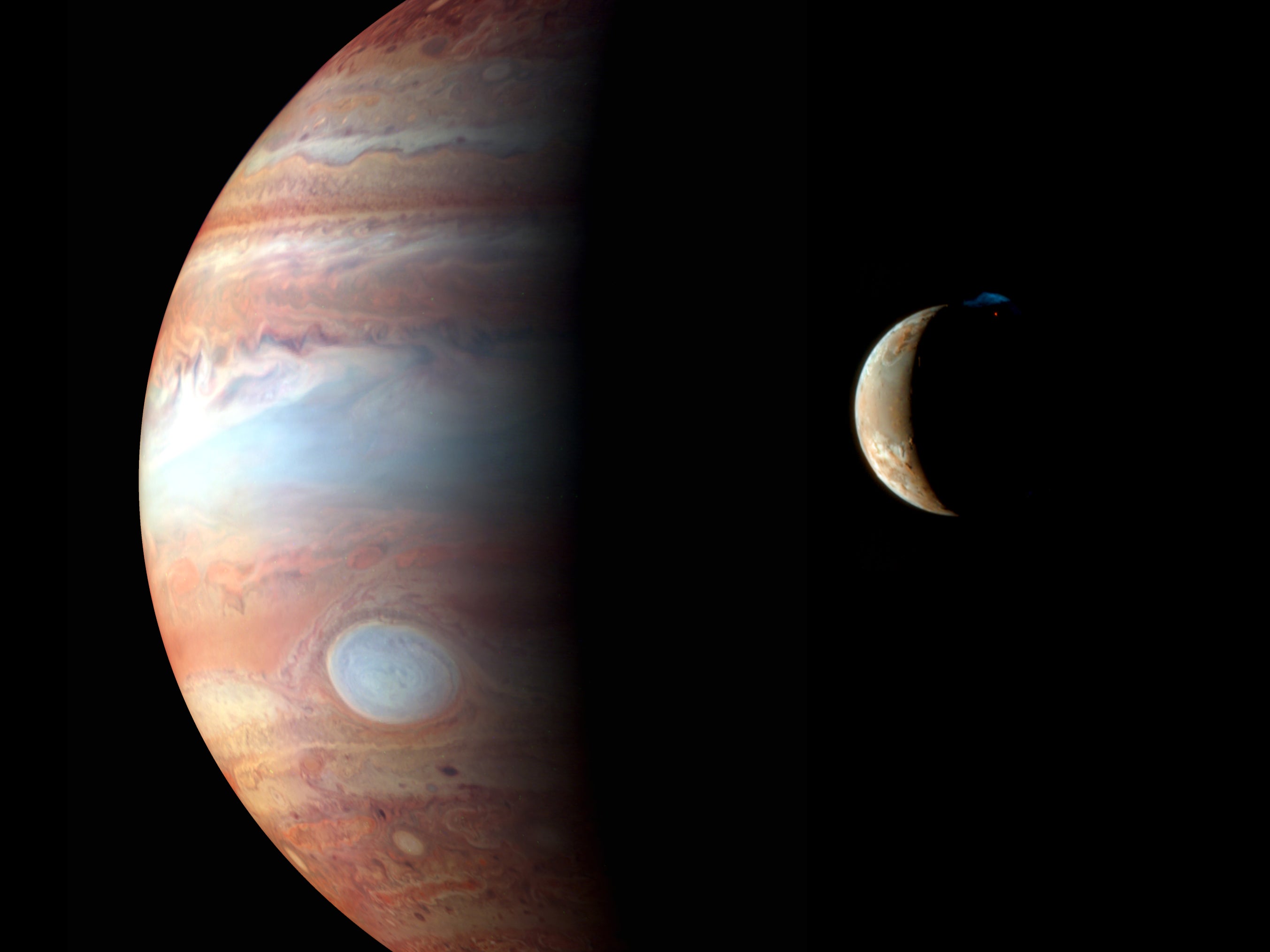

Scientists find ‘Jupiter’s twin’ planet in ‘hundreds of millions to one’ chance

Data from the Kepler telescope was used to discover the planet, orbiting a star 17,000 light years from Earth

Astrophysicists have discovered a ‘near-identical twin’ of Jupiter orbiting 17,000 light years from Earth.

The exoplanet, K2-2016-BLG-0005Lb, is almost identical to Jupiter in both its mass and its distance from the star it orbits. Spotted by the Kepler telescope, the planetary system is twice as distant as any of the 2,700 bodies that had been previously seen.

The system was discovered using gravitational microlensing, and is the first planet to be discovered using this method. The team from the University of Manchester searched through Kepler data collected between April and July 2016 to look for evidence of an exoplanet and its host star temporarily bending and magnifying light from a background star as it passes by the line of sight.

"To see the effect at all requires almost perfect alignment between the foreground planetary system and a background star", said Dr Eamonn Kerins, principal investigator for the Science and Technology Facilities Council.

“The chance that a background star is affected this way by a planet is tens to hundreds of millions to one against. But there are hundreds of millions of stars towards the centre of our Galaxy. So Kepler just sat and watched them for three months."

Spotting a planet 135 million kilometres from Earth is no easy task, but using five ground-based surveys of the same area of the night sky revealed conclusively that the signal is caused by a distant exoplanet.

"The difference in vantage point between Kepler and observers here on Earth allowed us to triangulate where along our sight line the planetary system is located", Dr Kerins explained.

"Kepler was also able to observe uninterrupted by weather or daylight, allowing us to determine precisely the mass of the exoplanet and its orbital distance from its host star. It is basically Jupiter’s identical twin in terms of its mass and its position from its Sun, which is about 60 per cent of the mass of our own Sun."

The microlensing method used to find this planet may have been unique for now, but it’s a technique that could be used in future to discover more worlds.

Nasa will launch the Nancy Grace Roman Space telescope in 2027, which could potentially thousands of distant planets. The European Space Agency’s Euclid mission will also launch next year and could also undertake a microlensing exoplanet search.

"Kepler was never designed to find planets using microlensing so, in many ways, it’s amazing that it has done so. Roman and Euclid, on the other hand, will be optimised for this kind of work. They will be able to complete the planet census started by Kepler.” Dr Kerins added.

“We’ll learn how typical the architecture of our own solar system is. The data will also allow us to test our ideas of how planets form. This is the start of a new exciting chapter in our search for other worlds."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks