Spacecraft using new iodine fuel could transform the space industry, study shows

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

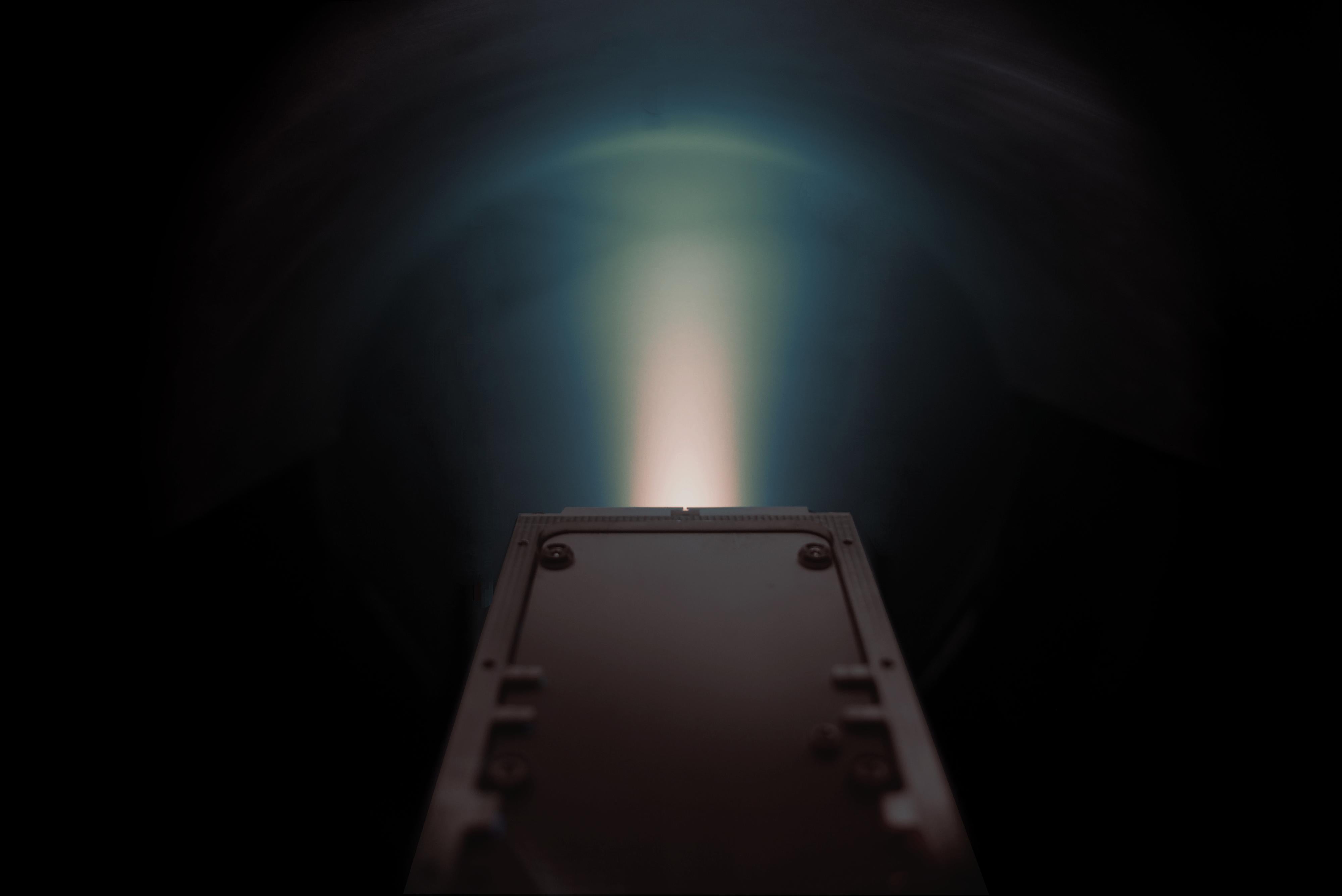

Your support makes all the difference.Engineers have successfully tested a spacecraft powered by iodine, in a development that could help transform spaceflight.

At the moment, spacecraft that use electric propulsion usually use xenon. But it is expensive, difficult to store and rare to find.

As such, the space industry needs to a propellant to replace it and help overcome those issues. One possibility is iodine.

Iodine is cheaper, found more easily, and can be stored in its solid form. It has also been found to be more efficient when it is used in tests on Earth.

Until now, however, a spacecraft has never been propelled entirely by an electric propulsion system using iodine.

In a new test, however, engineers were able to use such a spacecraft in the form of a small satellite in orbit over Earth. The new propulsion was demonstrated on a 20 kilogram satellite was was launched a year ago, which was moved in ways that were later verified using satellite tracking information.

They found that not only did iodine work, it was more efficient than xenon when used in space, too.

The research is reported in a new study, titled ‘In-orbit demonstration of an iodine electric propulsion system, published in Nature today.

In an accompanying article, scientists Igor Levchenko and Kateryna Bazakasaid that the findings could be a “game changer” in the use of small satellites.

Such small satellites have become a central part of space exploration and projects in recent years. In 2011, 39 such small satellites were launched into space, and that had risen to 389 in 2019 – in 2020, however, 1,202 of them were put into orbit.

That is expected to increase even more in the coming years. SpaceX alone hopes to put 42,000 satellites into space to power its Starlingspace internet system, and so a change of propellant could make such projects vastly cheaper.

That vast web of satellites is safer and more agile if they are able to move themselves to work as constellations. But moving them into such constellations relies on engines mounted on board the satellites – and those engines have until now largely relied on xenon.

The systems could help with other projects, too. In the future, engineers hope to be able to build equipment in space to take advantage of the effects of zero-gravity – and will be able to do much more cheaply if the product could be more efficiently moved out of orbit and back down to Earth.

Iodine does have its problems, however, which will need to be addressed before the technology reaches the mainstream. It is corrosive, for instance, and so could damage not only the engine’s own spacecraft but other satellites too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments