Scientists may have identified a 'powerful unknown mechanism' that is tilting planets

Many of the worlds that could harbour life also have a strange characteristic

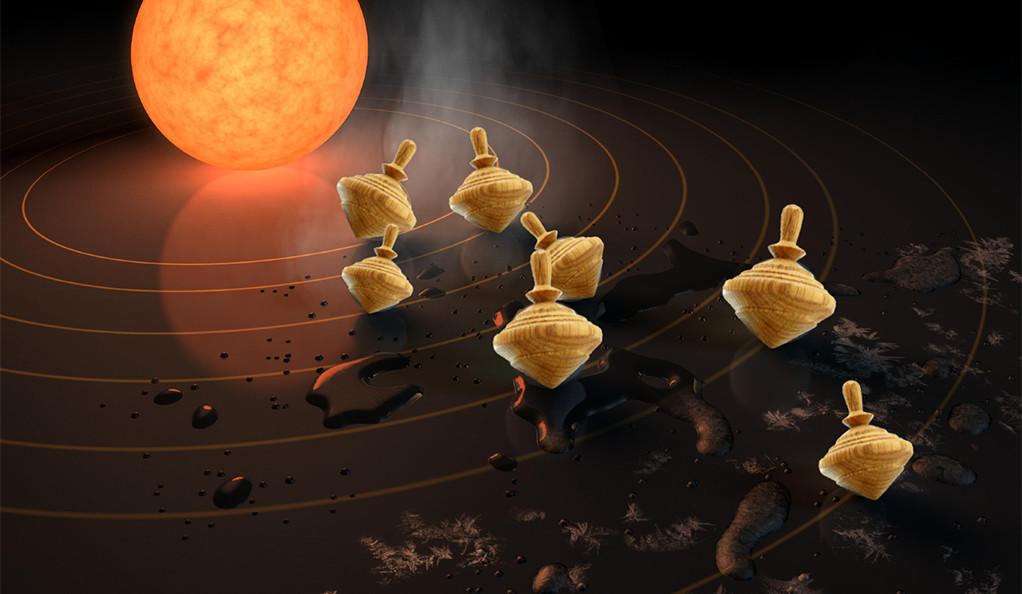

Scientists might finally have understood the strong, strange mechanism that is pulling planets into strange orbits.

For years, astronomers have been trying to explain how so many pairs of planets outside of our solar system are found in such an unusual configuration. Many of them seem to have orbits that have been pushed apart – but it is not clear what force did so.

Now scientists think they might have found the answer. And it seems to suggest there is something equally strange about the poles on the planets, which appear to be tilted off centre.

The discovery could change our understanding of exoplanets and their structure, climate, and habitability as we look around the universe for more places like our own Earth, the researchers say.

As it scanned the universe, Nasa's Kepler mission found about 30 per cent of stars similar to our own have super-Earths. Those planets are bigger than ours but smaller than Neptune, tend to go around their stars in a circular orbit, which takes less than 100 days.

Many of those planets also seem to be in pairs, with orbits that seem strange unstable.

Scientists now think this feature is explained by "obliquity", or how they are tilted between the axis and the orbit. The fact they are tipped over also seems to push them further apart, researchers Yale astronomers Sarah Millholland and Gregory Laughlin said.

“When planets such as these have large axial tilts, as opposed to little or no tilt, their tides are exceedingly more efficient at draining orbital energy into heat in the planets,” said first author Millholland, a graduate student at Yale. “This vigorous tidal dissipation pries the orbits apart.”

Earth and its moon are in a similar formation. The moon's orbit is slowly growing, but Earth's day is gradually lengthening, as the two go apart.

The tilting seems to decide a whole range of features about the planets.

“It impacts several of their physical features, such as their climate, weather, and global circulations,” Laughlin said. “The seasons on a planet with a large axial tilt are much more extreme than those on a well-aligned planet, and their weather patterns are probably non-trivial.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks