'Petya' computer virus spreads all the way across the world, but is gradually slowing down

The malware doesn't have anything like the 'kill switch' that stopped the Wannacry virus

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The computer virus that spread rapidly across the world is still making its way to more companies and countries – but is gradually slowing down.

The software doesn’t appear to be vulnerable to the same “kill switch” that stopped the similar Wannacry virus just weeks ago, however, and so is likely to continue to travel around the world.

The attack appeared to have started in Ukraine and then made its way across Europe, hitting companies including the world’s biggest advertising company in Britain and Danish international Maersk. It then continued to spread, arriving in the US and then in Asia.

Companies are still battling to contain and fix the problem, hours after it spread. But in many places they are failing – leaving staff advised only to shut off their machines and do as much as they can without electronic help.

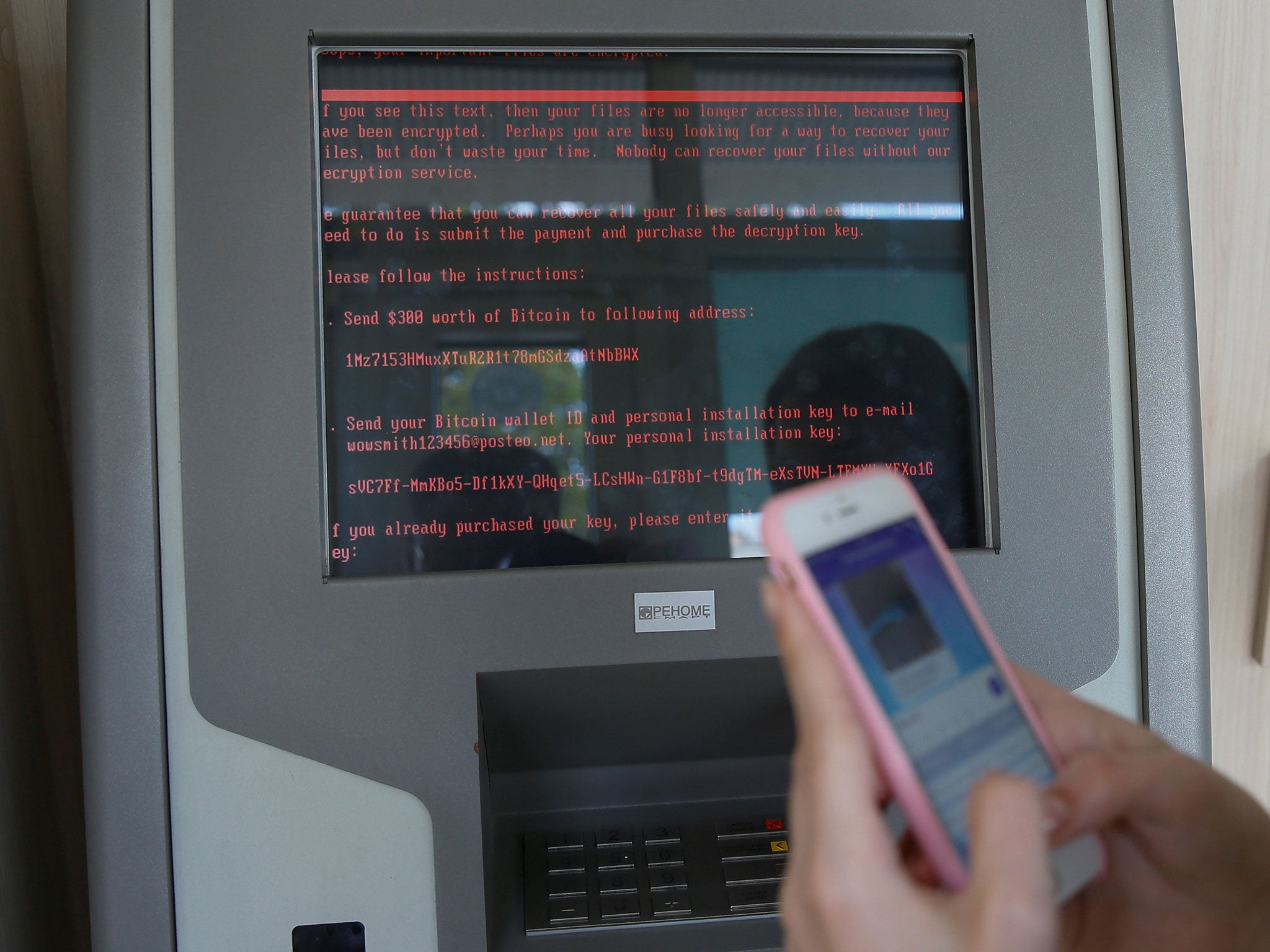

The software – which is going by a range of different names – locks down computers and asks for a $300 ransom in the form of bitcoin to make it work again. It’s no longer possible to pay that ransom, and most companies are instead trying to restore their computers from old backups.

The virus itself appears to be an updated version of a known virus, that fixes many of the ways it had been stopped in the past. As such, while researchers have developed a “vaccine”, it is more difficult to contain the problem and to restore systems that have already been affected.

The software is being referred to as GoldenEye, and is thought to be a more advanced version of the malware known as Petya. It uses an exploit known as EternalBlue, which was apparently developed by the US National Security Agency and was the same flaw that let the disruptive Wannacry virus into computers across the world – including those across the NHS, which was brought to its knees by the virus.

That time, the problem was stemmed by an accidental hero who found that the software had an unrealised “kill switch” built into it, which he was able to trigger and stop any further spread of the virus. This version of the software appears to be more advanced and harder to stop – leading to worries that it could be even worse than Wannacry.

That ransomware appeared to have originated in the UK and Spain before rapidly spreading across the world. It hit more than 200,000 victims in 150 countries before it was slowed down.

Those who patched their computers to keep them safe from that attack may still be vulnerable to the new one, experts suggested, because in changes to the way it worked.

Following last month's WannaCry incident some of the blame was directed at US intelligence agencies the CIA and the National Security Agency (NSA) who were accused of "stockpiling" software code which could be exploited by hackers.

Dr David Day, a senior lecturer in cyber security at Sheffield Hallam University, said he believed the latest attack is the "tip of the iceberg" and said he is frustrated at how it has been able to unfold.

He said: "Basically what they (the NSA) have done is they have created something which can be used as a weapon, and that weapon has been stolen and that weapon is now being used.

"And I think it underlines the whole need for debate over privacy versus security.

"The NSA will argue that the tool was developed with a need to ensure privacy, but actually what it's being used for is a weapon against security."

Companies across the world are rushing to shut down the virus. Those that aren’t affected are being urged to ensure that their computers are up to date and their security systems are running properly to stop any further spread.

WPP, the British advertising firm, said that a day after the ransomware struck, the company was still trying to restore services that had been disrupted.

In an email the firm said: "Having taken steps to contain the attack, the priority now is to return to normal operations as soon as possible while protecting our systems."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments