Scientists grow child an entirely new, genetically modified skin in world first

The boy was close to death when he was first admitted to hospital. Months later, he was playing football

A child has been saved from death after scientists grew him an entirely new skin.

The seven-year-old child was dying from a devestating inherited disease when he was first admitted to hospital. But months later, he had an entirely new coat of skin grown for him in a lab – and soon after that, he was not only saved but playing football.

Before the treatment, the boy was being killed by the condition, known as epidermolysis bullosa. It causes skin to blister and tear – as if it has been burnt or attacked – at just the lightest touch.

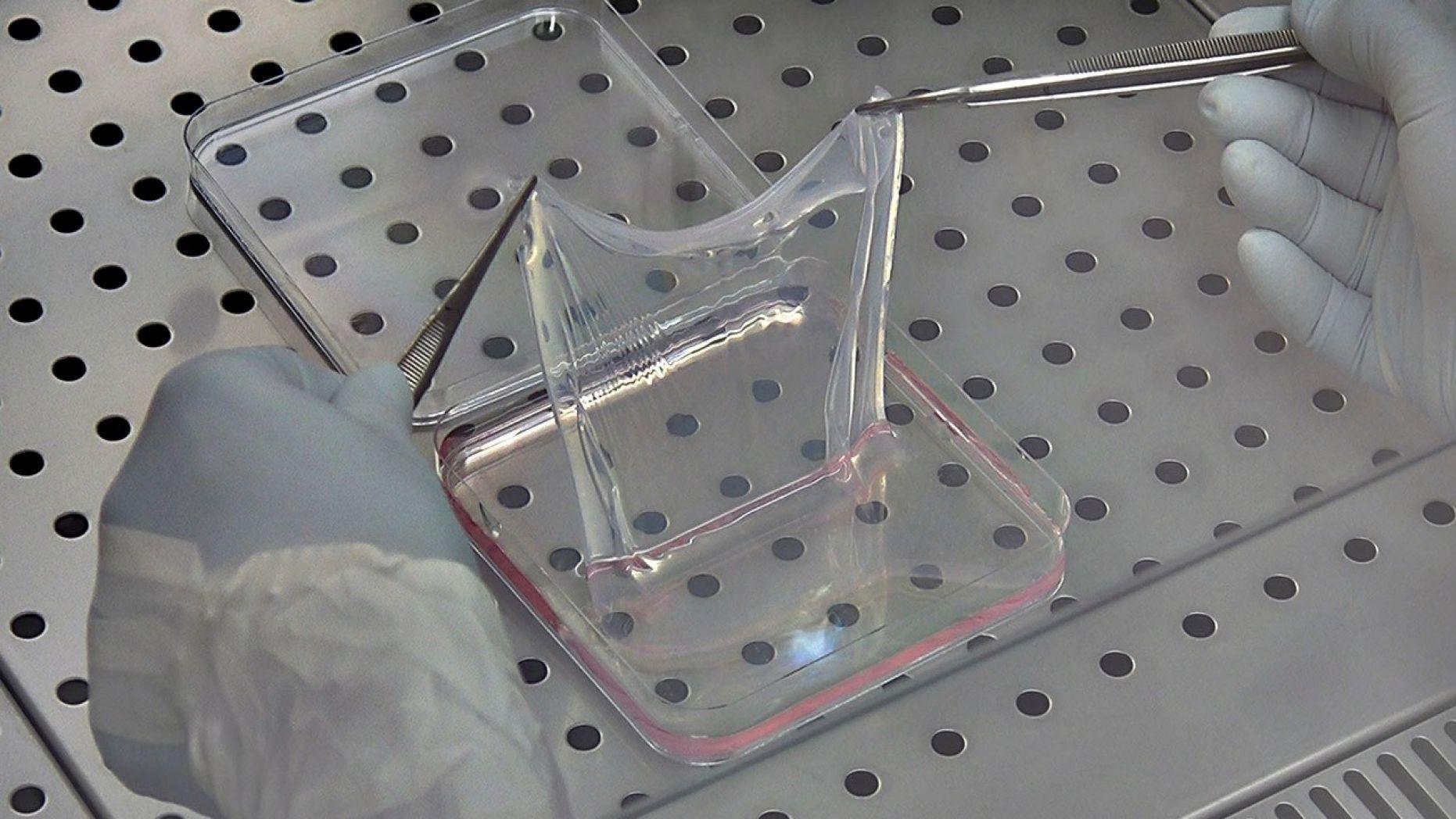

To try and save him from that, scientists took a tiny sample of skin from the child. They used genetic modification to remove the gene defect that lurked in its cells, and then grew that into a film that was large enough to cover most of the boy's body.

After 21 months the boy, who had been admitted to a hospital burns unit close to death, appeared to be fully recovered.

His new skin no longer blistered and was able to heal normally.

Returning to his home in Germany, he was able for the first time to enjoy the rough and tumble of a normal schoolboy's life.

Researchers describing his treatment said he was even playing football - something that previously would have been unthinkable.

Dr Michele de Luca, from the University of Modena, Italy, who led the gene therapy team, said: "The patient was in danger of life. The prognosis was very poor, but he survived.

"He went back to normal life, including school and sports. His epidermis is stable; robust. It doesn't blister at all and functionality is quite good."

The boy had been transferred to the burns unit at Ruhr-University, Bochum Children's Hospital in June 2015 with most of his epidermis - the outermost layer of skin - missing or horribly damaged.

All forms of standard treatment proved hopeless, and the child's body rejected grafts taken from his father.

In desperation doctors contacted experts in other countries, eventually getting in touch with Dr de Luca who was investigating experimental skin regeneration treatments.

The Italian scientists used a virus to insert a healthy version of the rogue Lamb3 gene into cells taken from the skin tissue sample.

Grown in the laboratory, the repaired cells produced colonies of regenerative "mother" stem cells.

These were used to create sheets of genetically modified tissue free from the terrible gene mutation that causes JEB.

Over the course of three operations surgeons attached the new skin grafts to the boy's body. Once established, the regenerated epidermis maintained itself.

Details of the treatment, previously only used to reconstruct small areas of skin in two patients, appear in the latest issue of Nature journal.

Plastic surgeon Professor Tobias Hirsch, from Bochum Children's Hospital, described the critical condition of the boy when he was admitted to the burns unit.

Speaking at a phone-in press conference, he said: "He'd lost nearly two-thirds of his skin. After two months we were absolutely sure we could do nothing for this kid and he would die."

Now the boy had "good quality" skin that was "perfectly smooth and quite stable" and required no treatment with special ointments.

Prof Hirsch added: "If he gets any bruises they just heal as normal skin heals."

He said the child was using a home trainer and playing football.

Treating the boy had provided useful scientific information that improved understanding of how skin was regenerated and maintained, said the scientists.

The research showed that the human epidermis is sustained by a small number of long-lived stem cells with a powerful ability to renew themselves.

These were vital to the process that allowed the skin to regenerate itself completely about once every month.

Writing in Nature, the scientists said: "Transgenic epidermal stem cells can regenerate a fully functional epidermis virtually indistinguishable from a normal epidermis.

"The different forms of epidermolysis bullosa affect approximately 500,000 people worldwide. The successful outcome of this study paves the way for gene therapy to treat other types of epidermolysis bullosa and provides a blueprint that can be applied to other stem cell-mediated ex-vivo (outside the body) cell and gene therapies."

Additional reporting by agencies

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks