Nasa telescope spots mysterious ‘free-floating planets’ not attached to any solar system

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

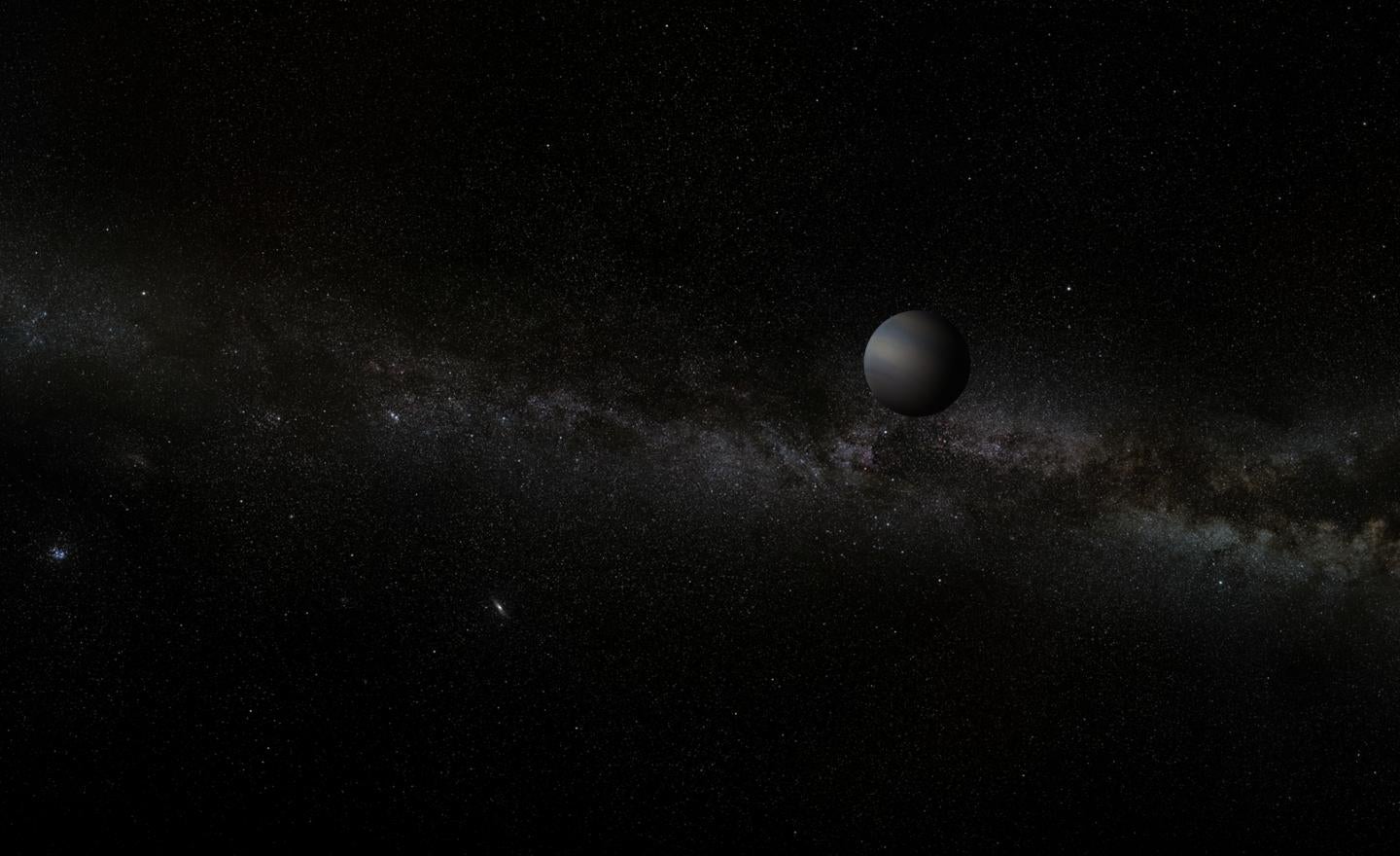

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have seen evidence of a mysterious set of “free-floating” planets, making their way through deep space without being attached to any star.

The research was done using Nasa’s Kepler Space Telescope, which captured intriguing signals that suggested there are Earth-sized planets hiding within space.

Those signals were not, however, matched by a longer signal that might be expected if they were joined by a host star, like our Sun.

Researchers suggest therefore that the stars might once have formed around their own star, before being thrown out of their solar system by the gravitational effect of other, heavier neighbours.

The signals were captured by using the principle of “microlensing”, which was first predicted by Albert Einstein. It happens when stars in the foreground can act like magnifying glasses for stars behind them, which can be seen as bursts of brightness.

Most such rare incidents are caused by stars. But a small number of that very small number of incidents are caused by planets.

It was signals that looked like they were caused by other worlds that were captured by scientists in the new study – despite the fear that they could never actually be found.

“These signals are extremely difficult to find,” said Iain McDonald, from the University of Manchester, who led the research.

“Our observations pointed an elderly, ailing telescope with blurred vision at one the most densely crowded parts of the sky, where there are already thousands of bright stars that vary in brightness, and thousands of asteroids that skim across our field.

“From that cacophony, we try to extract tiny, characteristic brightenings caused by planets, and we only have one chance to see a signal before it’s gone. It’s about as easy as looking for the single blink of a firefly in the middle of a motorway, using only a handheld phone.”

The Kepler Space Telescope was never intended for this kind of work. Its primary job is to look for other planets by watching for the shadows they cast when they cross in front of their stars.

“Kepler has achieved what it was never designed to do, in providing further tentative evidence for the existence of a population of Earth-mass, free-floating planets,” said Eamonn Kerins, also from the University of Manchester, who was a co-author on the study.

“Now it passes the baton on to other missions that will be designed to find such signals, signals so elusive that Einstein himself thought that they were unlikely ever to be observed. I am very excited that the upcoming ESA Euclid mission could also join this effort as an additional science activity to its main mission.”

Those missions – and other research by Nasa and different space agencies – will be looking to confirm the existence of those free-floating planets, and what they might look like.

A paper detailing the findings is published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments